Cosmic Grim Reaper Seen For First Time

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Like acosmic Grim Reaper, a blast of ultraviolet light signals the violent death ofthe universe's most massive stars. Now astronomers have viewed this heavenlyharbinger for the first time.

"Astronomershave been dreaming about seeing the first light from the violent death of astar for over 30 years," said lead researcher Kevin Schawinksi of the University of Oxford. "Our observations open up an entirely new avenue for studyingthe final stages in the lives of massive stars and the physics ofsupernovae."

Schawinksiand his colleagues detected the ultraviolet signal of a hefty star on the vergeof explosion, which they detail in the June 13 issue of the journal Science.

Usually,when astronomers see a supernova, the star has already been destroyed. "It'svery hard to tell much about precisely the kind of star that actually diedthere," Schawinski told SPACE.com. "The really cool thingabout our observations is this light traveling ahead of the shock wave traveledthrough the star before it was destroyed."

He added,"It's telling us about the properties, the conditions, of the star at themoment it died, but before the shock wave actually disrupted it."

Doomedstar

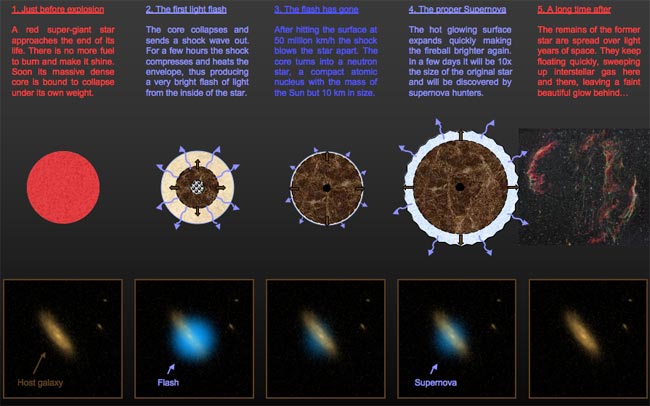

When amassive star, weighing at least 10 suns, runs out of nuclear fuel, it cancollapse under its own weight, triggering an explosion called a supernova. Theexplosion sends the stellar gutsspewing away at 20 million mph (10,000 km/sec) in a fireball that's abillion times brighter than the sun, the researchers say.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It's thisfireball that scientists observe. What they haven't seen until now are thefinal moments of the doomed star just before the visible explosion. For thepast 30 years or so, theorists have predicted a surge of ultraviolet lightshould come before the actual visibleexplosion.

There areseveral problems for actually seeing this phenomenon. "By the time you seethe supernova, it's already days or weeks in the past," Schawinski said."If you see a supernova you'd have to go back in time. You'd have to bealready looking at the position."

The otherissue is the fact that Earth's atmosphere absorbs ultraviolet light, and soyou'd need a space telescope to actually be able to view the death beacon. Thespace telescope GALEX, which orbits Earth about every 98.6 minutes and views theuniverse in ultraviolet, was the answer.

With GALEX,researchers recently got front-row seats to the pre-show of what they suspectwas a red supergiant star measuring somewhere between 500 and 1,000 solar radiion the verge of explosion. A redsupergiant is a hefty star nearing the end of its life that can swell to100 times its original size before exploding.

Schawinskiand his colleagues looked at GALEX images taken at the positions of supernovaepreviously identified with optical telescopes in Hawaii.

"We founda new source at the location of one supernova, suddenly outshining its galaxy hostin the UV," said Mark Sullivan of the University of Oxford. "Itappeared a couple of weeks before the optical discovery of the supernova andmarked the first stage in the death of the star."

Thefinal hours

The UV peakrepresented a unique phase in the formation of the supernova SNLS-04D2dc, justbefore the shock wave from its collapsed core reached the star's surface toviolently eject its shell of hot gas.

During ared supergiant's final hours, a shock wave whizzes outward with the relatedradiation moving even faster and heating up the star's surface. The temperatureat the surface ramps up from a few thousand degrees Celsius to several hundredthousand degrees. Just before the shock wave catches up and reaches the surface(triggering a supernova), the star is producing the same total luminosity as athousand billion suns, the researchers say.

Once theshock wave catches up, it plows through the outer parts of the star,accelerating several suns' worth of material outward. The surface of thestar explodes. A few days later, supernova hunters will spot the brightvisible light of the explosion.

Schawinskidescribes the observations as looking inside of a semi-transparent star as it'sdying.

"Wesaw the whole thing. We saw the radiative precursor, this UV light, movingahead [of the shock wave]," Schawinski said. "We saw that arrive andthen the point at which the shock wave comes to the surface and destroys thestar. In a sense we could see the shock move inside the star because the lightfrom the shock was moving ahead of it."

The new UVpeak findings, the astrophysicists say, will shed light on deathly details oncehidden beneath a star's outer cloak.

"Thisis a whole new avenue into studying the late stages of massive stars,"said Oxford researcher Christian Wolf. "Most of what we know today isbased on computer simulations. But as always when you test theory againstobservations for the first few times, we may be in for surprises."

- Video: Supernova Destroyer/Creator

- Top 10 Star Mysteries

- Vote Now: The Strangest Things in Space