Marrying Mars: Fixing Our Dysfunctional Relationship with the Red Planet (Op-Ed)

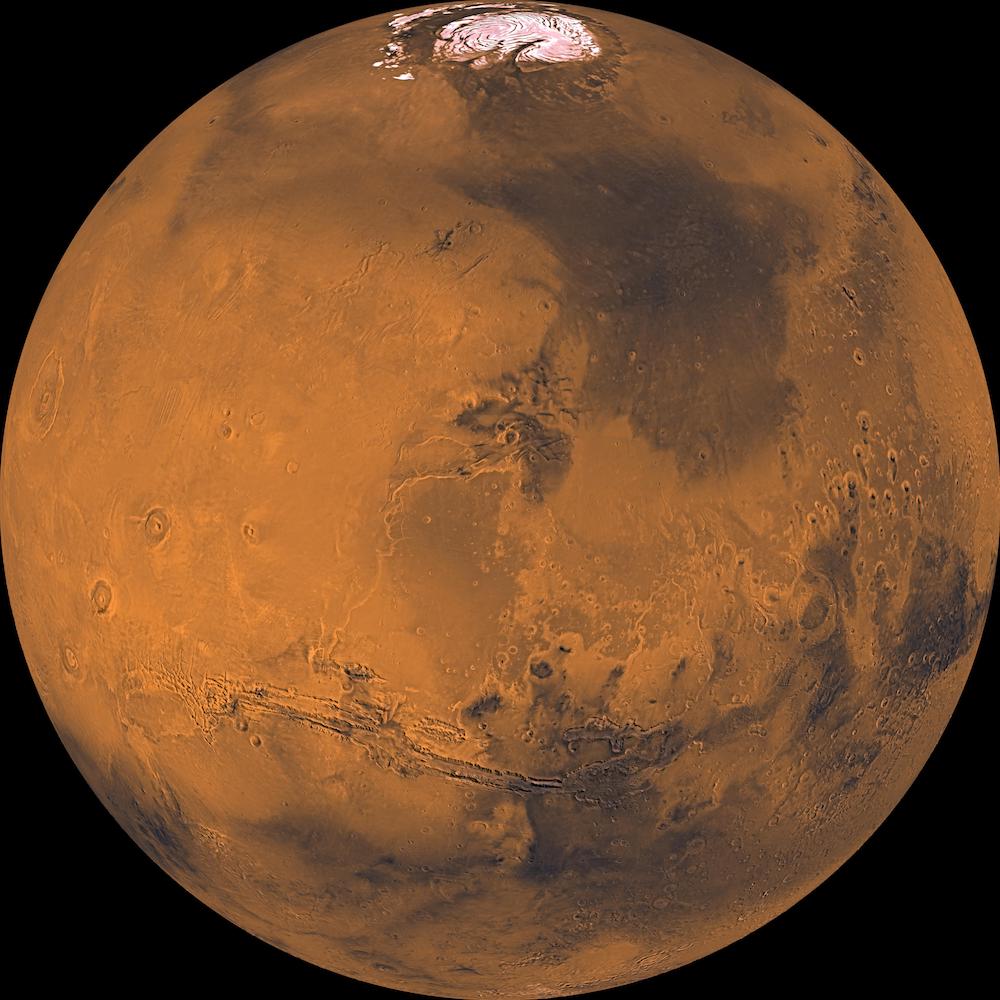

It's time to get serious about our relationship with Mars. We've been enthralled with the rose-gold-colored planet Mars since Egyptian skywatchers noticed its peculiar apparent motion in the sky. Mars pauses, backtracks, surges forward again. It draws nearer, growing brighter, every 26 months, then slinks away into the background of stars. It's like Mars is flirting with us.

Typical of human dating behavior, we've often let ourselves believe wild fantasies about this celestial object of our affection. We've imagined that great intelligence, or deep malevolence, or our own salvation dwells there. The rocket-transport and life-support technologies needed to go in person will very soon be available. But, if we really plan to move in with Mars, we had better commit to this marriage with eyes wide open.

Mars will try to kill us. Slowly, by solar energetic particles and ultraviolet radiation. Quickly, by asphyxia in its ultrathin, oxygen-poor atmosphere. It wants to damage our thyroid glands with caustic perchlorates (the compounds that give fireworks their bang) littered everywhere on its surface. It seeks to freeze-dry us in sub-Antarctic temperatures and desiccating desert conditions about 500 times drier than anywhere on Earth. It's as if Mars is putting the human species through trials, to see if we are a worthy suitor. [How Living on Mars Could Challenge Colonists (Infographic)]

In strict scientific method, "anthropomorphizing" (endowing non-human entities or processes with human characteristics) is a dodgy practice. It can snooker a researcher to perceive sentient intent, or intelligent planning, where neither is present. We form our imperfect understandings of the universe because we're emotional creatures first and intelligent creatures second. Our brain lives in a dark box. We tell ourselves an ever-evolving story, woven of often-noisy sensory data, that we take to be the truth. When we guess right, we call in insight or inspiration. A hunch based on experience can lead to a leap of understanding.

Much more often it goes wrong, and (upon reflection) we call it cognitive bias. Preconceptions and prejudices are likely to suck us into long blind alleys with distant dead ends. Exactly this is happening, right now, as we try to get Mars to be honest with us.

Not who you think she/he is

ety Landscape images taken by Mars rovers such as Curiosity and Opportunity look like parts of the Southwest U.S., or Wadi Rum in southern Jordan, where exterior shots for "The Martian" movie were filmed. But don't be deceived. As Steve Squyres, principal investigator for NASA's Mars Exploration Rovers mission, once cautioned this author, "I've been to Wadi Rum, and I've 'been' to Mars. Mars is not Wadi Rum."

These pictures look so vibrant because the cameras are so very cold, lowering noise in the image sensors, and the atmosphere is so very dry and thin (when it's not choked with the fine dark dust of a planetwide storm). If all the water vapor in Mars' "air" were to condense out, the rocks would be coated with less than 0.04 inches (1 millimeter) of ice. Mars' gaseous envelope is a ghost, its body lost to space more than a billion years ago. The small planet's low gravity and frail magnetic field could not hold on to it as intense ultraviolet light and strong solar winds sputtered most of the gas molecules away.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Through telescopes, too, Mars has hoodwinked us. From 1894 though his death in 1916, Percival Lowell consistently saw what he believed on Mars: a dying Martian civilization, desperately trying to engineer survival tools against a drying desert world. He'd gotten there because many generations of observers before him had embroidered a rich narrative of intelligent inhabitants — a mass delusion likely rooted in the desire to not be the lone intelligent species in the observable cosmos. With 21tst-century hindsight, it's easy to poke fun at Huygens, Herschel, Schiaparelli, Pickering, Lowell, Lampland and others. But these were good astronomers wielding the best telescopes of their day. Yet they all got duped by their own wishful seeing.

At the same time, more careful observers escaped Mars' masquerade. Edward Barnard could find no straight lines anywhere on the planet. Edward Maunder demonstrated how human eyes could easily be tricked into seeing linear features where none existed. William Campbell and his spectrograph found not a trace of water in Mars' atmosphere.

Are you alive?

Again and again, the Red Planet teases us with the promise of life but never quite delivers. NASA's twin Viking landers, equipped to hydrate and nourish Martian soil to see if anything would breathe out detectable biomarkers, yielded an enticing but inconclusive answer after touching down in 1976. And Mar's possible unexpected perchlorates could have helped incinerate organics found four decades later by Curiosity. Space science writer Leonard David put it this way: "We asked Mars, 'Do you have life?' And Mars responded: 'Can you repeat the question?'"

In 1996, a group of excellent scientists headed by David McKay thought they could be looking at microfossils and chemical signatures of past Martian life in a Mars meteorite dispatched to Earth. Most present-day researchers are deeply skeptical of this find.

Recently, tantalizing data gathered by Curiosity over several yearly cycles shows Mars exhaling methane in warmer seasons. Each year, methane levels drop in winter. It could be a marker of biology, or just a geochemical process at work.

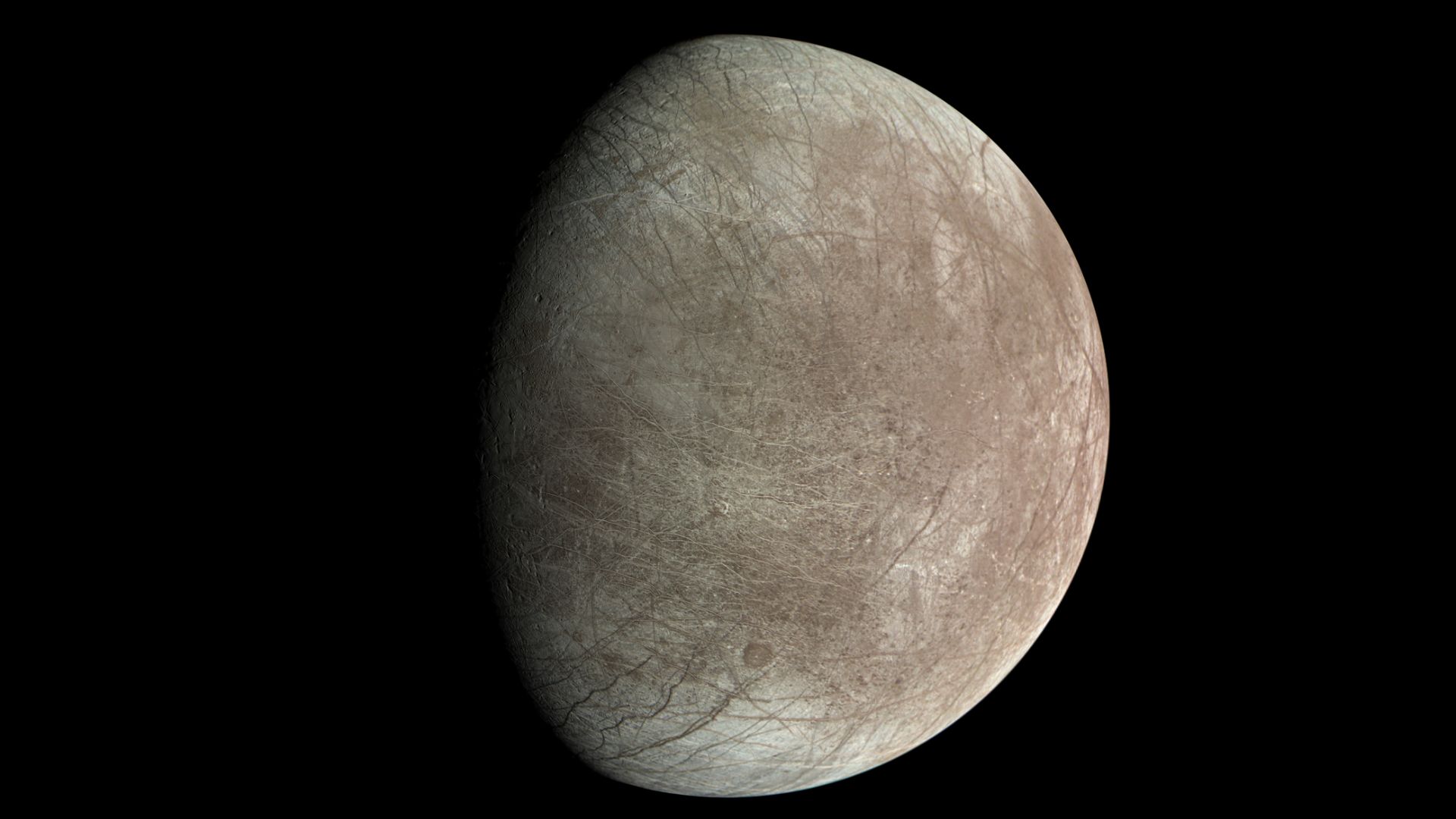

Recently, researchers found, in the ground-penetrating-radar data of the European Mars Express spacecraft, the signature of a large subterranean lake of liquid water beneath the south polar cap. There's probably no naturally occurring body of liquid water on Earth that does not contain some form of life. But if there's anything alive anywhere on Mars, it sure doesn't seem to be living large. [The Search for Life on Mars (A Photo Timeline)]

As of this writing, our faster-orbiting Earth has just swung past the point where the sun and Mars lie on opposite sides of our sky. On the timescale of human civilization, this encounter was unusually close and bright. Mars' orbit is considerably more eccentric than Earth's, so much so that its varying distance from the sun plays a role in Martian seasonal temperature swings. (Earth's orbital distance is not a significant seasonal factor.) Such cyclical encounters, over the past four centuries, seduced astronomers, writers and dreamers into recurrent speculations: The oncoming Mars propelled construction of larger telescopes. The receding Mars allowed time for rumination (frequently wrong), writing up results (often in error), and colorful conjecturing (frequently hilariously misguided).

We take a much deeper dive into the history of Mars and our relationship with it in our film, "Mars Calling – Manifest Destiny or Grand Illusion," now on Amazon Prime Video.

Given our twisted history of misguided Mars science, and our many botched attempts to send spacecraft there (of 50 missions launched, more than half have failed), it can seem like the planet wants to throw us under the bus. But we still appear to be in love with it.

Like a flock of geese trying to motivate one another to take flight, humans seem increasingly restless to lift off for Mars. It's a healthy sign that there are as many different approaches to getting there as there are entities that want to go. Some want to stay and build a new world; others aren't ready to pledge permanent allegiance. In 2033, especially favorable orbital mechanics will offer a great shot at getting humans to Mars. Who will be ready, and how will they pay for it?

Ways to go

Aerospace giant Boeing has blueprinted an "Affordable Mars Mission" around its planned solar electric sailing ship, the innovative Deep Space Transport Vehicle. After an eight-month crossing of the black void to low orbit around Mars, explorers would descend in a crew lander protected by an inflated "aeroshell." Once on the ground, they'd find a previously landed cargo ship with an inflatable habitat nearby. But Boeing isn't likely to go anywhere near Mars unless it's paid (by taxpayers) to do so.

Friendly rival Lockheed Martin thinks of exploring Mars like conquering Mount Everest, but upside down. "Lock-Mart" proposes an orbiting Mars Base Camp, built of pairs of identical modules. Taking along two of everything would preserve expedition success even if there's a major failure far from any help. Astronauts would mount assaults down to the surface using a single-stage lander/launcher shuttle.

In 1990, engineers Robert Zubrin and David Baker, then at Lockheed Martin, extensively researched the idea of robotic landers making rocket propellant from materials already on Mars.Native water, for example, can be dissociated to form hydrogen and oxygen. This "in-situ resource utilization" (ISRU) is a foundational dynamic of Zubrin and Baker's "Mars Direct" architecture. It could offer something of an insurance policy for mission safety, but neither Lockheed's Base Camp nor Boeing's Affordable nMars leverage an ISRU approach.

But SpaceX, always the disruptor, does. The 42 Raptor engines for its huge BFR) ("Big Falcon Rocket") spaceflight system are designed to guzzle cold liquid methane and liquid oxygen made on Mars. Also, unlike its traditional contractor competitors, SpaceX says that it wants to facilitate large numbers of people permanently inhabiting Mars. By mass-producing a BFR fleet, SpaceX intends to drive down the cost of carrying a single astronaut from $10 billion (NASA reference design) to about $200,000. The company believes that 1 million people could be living on Mars within 100 years. [The BFR: SpaceX's Mars-Colonization Architecture in Images]

Formerly secretive Blue Origin has lately teased glimpses of its grand unified space infrastructure. Blue Origin's plans include commerce on the moon, and likely the eventual construction of voluminous human-rated spaces in favorable orbits, whether or not Nature saw fit to put a celestial body there. Mars would get done in the logical course of this ambitious expansion, not as a single program — not as a mission of ego.

Conversely, NASA's baseline architecture — the Space Launch System megarocket combined with the Orion capsule, a "transit habitat," plus some kind of Mars excursion lander — practically guarantees a finite "flags and footprints" exercise. As with Apollo's conquest of the moon, a publicly funded program from a democratically elected government carries political risk: Administrators are driven to declare victory early, before disaster can strike. There's pressure to pack up and go home before much deep, dangerous exploration can be done. It's not sustainable, and not meant to be; it's actually the antithesis of settling the solar system.

Poised to swindle us again

So, what are we to make of Mars? Having grown up on the outside of a globe, it seems natural we should see a neighbor with Earth-like terrain as a potential second home. But that "fixer-upper planet," as SpaceX President Gwynne Shotwell has called Mars, comes with a toxic mortgage: All the good stuff lies down a gravity well, on a picturesque but perilous surface. Mars could be a bait-and-switch scam. You migrate to Mars drawn by its wide-open spaces and find yourself bottled up underground most of the time. Mars might remain scary, uncomfortable, boring and risky until we change the planet, or it changes us.

We may erect better places in space, sooner than we can make Mars safe enough for city-scale populations. With the astonishing level of aerospace engineering talent now employed at big-old and small-new space companies, it may soon be practical to build large habitable volumes orbiting where we really want them. For the next few generations, it's likely that most folks would rather be days or hours from Earth, not weeks or months. And the view of our first home-planet would be terrific.

Certain near-Earth asteroids are simpler get to — and richer in water and metals — than the surface of the moon. It's reasonable to assume that use of tele-operated machines, autonomous robots and deployment of task-directed artificial intelligence (AI) will let this type of construction scale up very quickly. Long before it becomes practical to totally terraform Mars, we could have many times its land area in purpose-built space structures that are friendlier to people.

Such structures could be spun to simulate gravity by centripetal acceleration. We don't yet know the long-term biological effects of less-than-Earth-normal gravity. Living in Mars gravity might be beneficial to human bodies, or it could prove detrimental. But it may turn out that we could re-engineer human physiology to better adapt to Mars. That would make the fourth planet a brave new world indeed. [The 7 Biggest Mysteries of Mars]

Relationship boundaries

What do we really want out of our liaison with the Red Planet? Is it perilous to bring samples back to Earth? Or obviously safe because Mars has been sending us (possibly microbe-laden) meteorites for billions of years? Is it worth the physical and psychological dangers to go in person? Or do we owe it to future generations to take those risks? What should astronauts do there? Or can we search for life and prospect for resources with our increasingly intelligent machines? Do we have the right to bring Mars (back?) to life? Or might we have the responsibility to do so?

If we could take our romantic blinders off, we'd realize that it's going to be a lot harder to live and work on Mars than most people who claim to want to go there will be able to tolerate. Pioneering in person will be a much more challenging existence than those raised on modern technology's comforts and conveniences are prepared to deal with. Worse, as entertainment and information media grow increasingly immersive, we may find we have little incentive to explore at all. If it can't be done by camera-drone, we may lose interest in doing it at all.

In the past, we restless humans have consistently expanded our range into ever more challenging surroundings. We are constantly innovating ways to modify environments to suit us, though it often takes a few disasters before we allow ourselves to see the unintended consequences. And better we should experiment with Mars before continuing to mindlessly change the climate of Earth. Our emerging AI-driven tools could soon let us scale our ecological tinkering to alter entire planets, waking up biology on the fourth one from the sun.

Until then, a human trying to settle on Mars will feel like a Na'vi of the "Avatar" movie universe, trying to tame his or her flying banshee. It may become wholly devoted to you. But first it will try to murder you.

Check out "Mars Calling – Manifest Destiny or Grand Illusion," on Amazon Prime Video.

The author, @DavidSkyBrody, a science filmmaker, was formerly executive producer at Purch, the parent company of Space.com and Live Science. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Dave Brody has been a writer and Executive Producer at SPACE.com since January 2000. He created and hosted space science video for Starry Night astronomy software, Orion Telescopes and SPACE.com TV. A career space documentarian and journalist, Brody was the Supervising Producer of the long running Inside Space news magazine television program on SYFY. Follow Dave on Twitter @DavidSkyBrody.