RIP, Kepler: NASA's Revolutionary Planet-Hunting Telescope Runs Out of Fuel

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

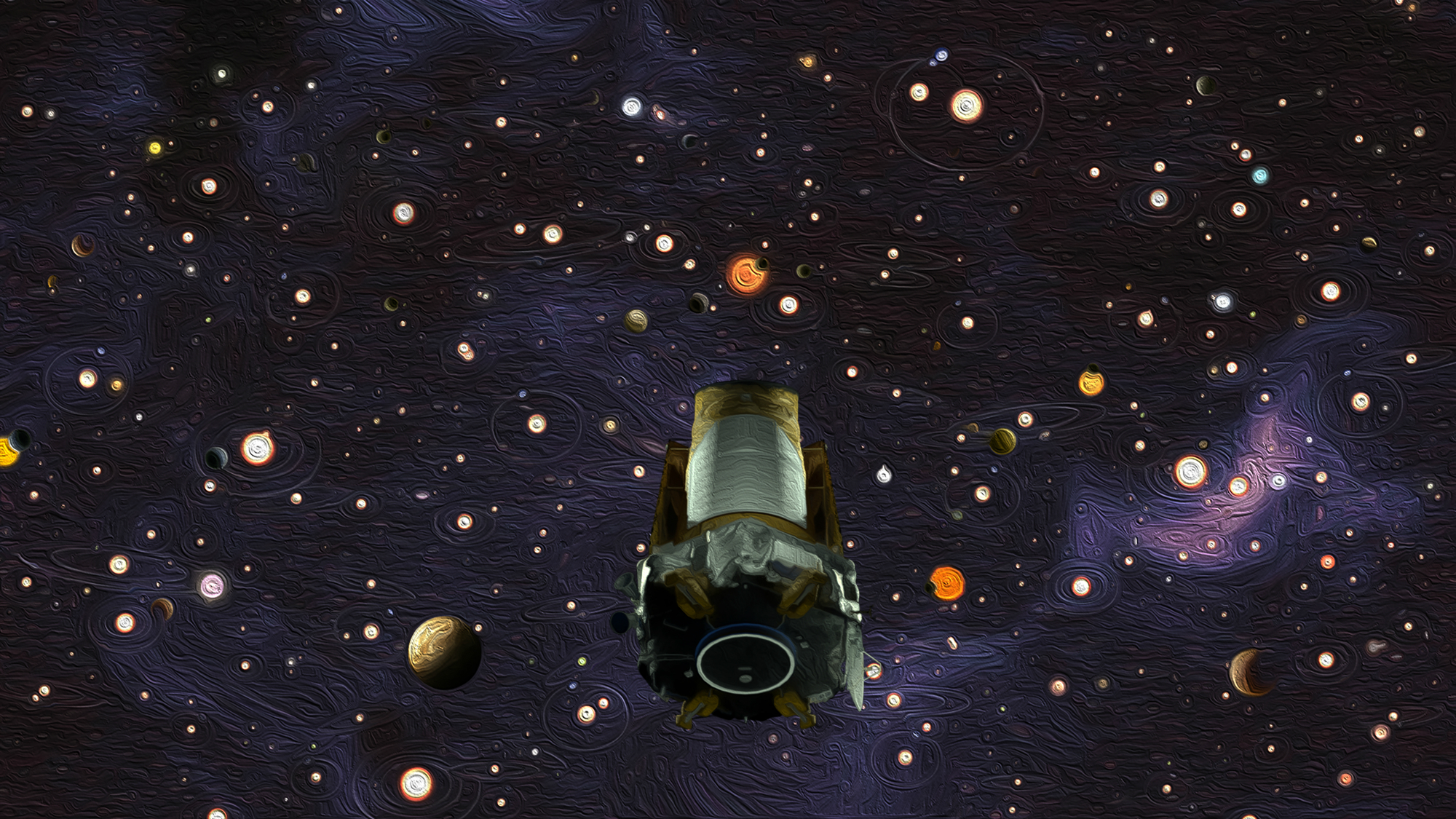

The most prolific planet-hunting machine in history has signed off.

NASA's Kepler space telescope, which has discovered 70 percent of the 3,800 confirmed alien worlds to date, has run out of fuel, agency officials announced today (Oct. 30). Kepler can no longer reorient itself to study cosmic objects or beam its data home to Earth, so the legendary instrument's in-space work is done after nearly a decade.

And that work has been transformative. [Kepler's 7 Greatest Exoplanet Discoveries]

"Kepler has taught us that planets are ubiquitous and incredibly diverse," Kepler project scientist Jessie Dotson, who's based at NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, told Space.com. "It's changed how we look at the night sky."

Today's announcement was not unexpected. Kepler has been running low on fuel for months, and mission managers put the spacecraft to sleep several times recently to extend its operational life as much as possible. But the end couldn't be forestalled forever; Kepler's tank finally went dry two weeks ago, mission team members said during a telecon with reporters today.

"This marks the end of spacecraft operations for Kepler, and the end of the collection of science data," Paul Hertz, head of NASA's Astrophysics Division, said during the telecon.

Leading the exoplanet revolution

Kepler hunted for alien worlds using the "transit method," finding the brightness dips caused when a planet crosses its star's face from the spacecraft's perspective.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Those dips are tiny — so tiny, in fact, that NASA officials were originally dubious that a spacecraft could make such measurements. The driving force behind Kepler, Ames' Bill Borucki, had four mission proposals rejected in the 1990s before finally breaking through in 2000, after he and his team demonstrated the instrument's sensitivity at a test-bed facility on Earth. (Borucki retired in 2015.)

It still took a while for Kepler to get aloft. The spacecraft launched in March 2009, on a $600 million mission to gauge how common Earth-like planets are throughout the Milky Way galaxy.

Initially, Kepler stared continuously at a single small patch of sky, studying about 150,000 stars simultaneously. That work was incredibly productive, yielding 2,327 confirmed exoplanet discoveries to date.

In May 2013, however, the second of Kepler's four orientation-maintaining "reaction wheels" failed. The spacecraft couldn't keep itself steady enough to make its ultraprecise transit measurements, and Kepler's original planet hunt came to an end.

But the spacecraft wasn't done. Kepler's handlers soon figured out a way to stabilize it using sunlight pressure, and, in 2014, NASA approved a new mission called K2. (Sending astronauts to service Kepler is out of the question; the spacecraft orbits the sun, not Earth, and is millions of miles from our planet.)

During K2, Kepler studied a variety of cosmic objects and phenomena, from comets and asteroids in our own solar system to faraway supernova explosions, over the course of different 80-day "campaigns." Planet-hunting remained a significant activity; the K2 alien-world haul stands at 354 as of today.

Kepler's observations over both of its missions suggest that planets outnumber stars in the Milky Way and that potentially Earth-like worlds are common. Indeed, about 20 percent of sun-like stars in our galaxy appear to host rocky planets in the habitable zone, the range of distances where liquid water could exist on a world's surface.

"Kepler's exoplanet legacy is absolutely blockbuster," Dotson told Space.com.

But the mission's legacy extends to other fields as well, she stressed. For example, Kepler's precise brightness measurements — which the telescope has completed for more than 500,000 stars — are helping astronomers better understand the inner workings of stars. And the instrument's supernova observations could shed considerable light on some of the most dramatic events in the universe.

"We've seen explosions as soon as they happen, at the very beginning," Dotson said. "And that's very exciting if you'd like to figure out why things go, 'Boom!'"

Not done yet

Even though Kepler has closed its eyes, discoveries from the mission should keep rolling in for years to come. About 2,900 "candidate" exoplanets detected by the spacecraft still need to be vetted, and most of those should end up being the real deal, Kepler team members have said.

A lot of other data still needs to be analyzed as well, Dotson stressed.

And Kepler will continue to live on in the exoplanet revolution it helped spark. For example, in April, NASA launched a new spacecraft called the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which is hunting for alien worlds circling stars that lie relatively close to the sun (using the transit method, just like Kepler).

Some of TESS' most promising finds will be scrutinized by NASA's $8.9 billion James Webb Space Telescope, which is scheduled to launch in 2021. Webb will be able to scan the atmospheres of nearby alien worlds, looking for methane, oxygen and other gases that may be signs of life.

Kepler's death "is not the end of an era," Kepler system engineer Charlie Sobeck, also of NASA Ames, told Space.com. "It's an occasion to mark, but it's not an end."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.