Autumn Skywatching Treat: See Uranus and Neptune in the Night Sky

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Midautumn places the two outermost planets in excellent position for viewing.

We often speak of the five "naked-eye" planets (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn), but in actuality, there is a sixth that can be glimpsed with the unaided eye if you know precisely where to look — and another that can be seen when you use a good pair of binoculars. Uranus can also be seen by a sharp-eyed observer who knows where to look for it; Neptune is the only planet that requires optical aid in order to be seen.

Both planets were discovered after the invention of the telescope. Uranus was discovered more or less by accident in 1781. Uranus' failure to follow its predicted orbit seemed to be due to the gravitational pull of a planet farther out in space. Two astronomers independently calculated the position of the undiscovered planet, and when telescopes were turned to this region in 1846, Neptune was found. [Stargazing Maps: Best Night Sky Events of October 2017]

So, while our evening sky will soon be devoid of bright planets (Saturn will depart the scene by early December), Uranus and Neptune will be in excellent positions to be seen.

Of course, the trick is that you'll have to know exactly where to look!

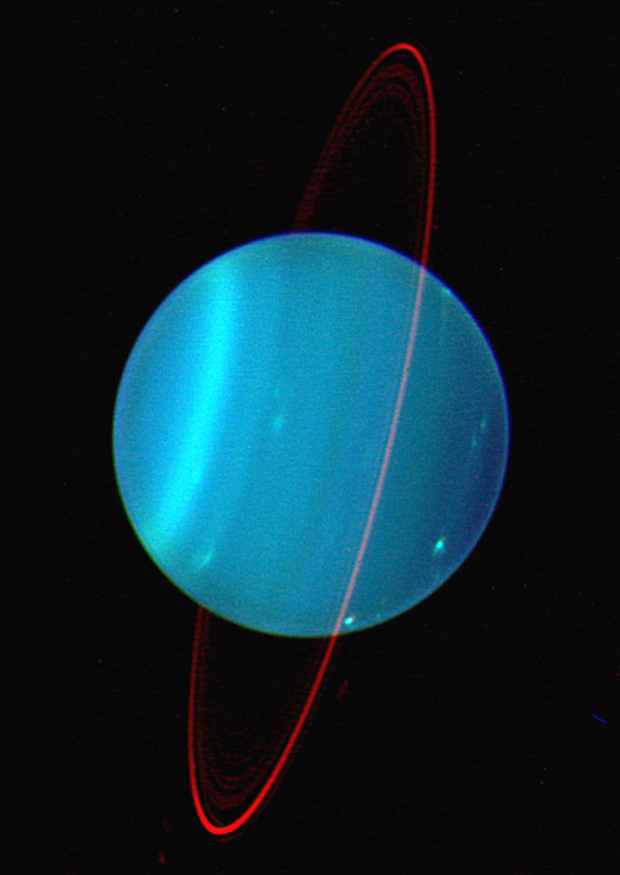

Uranus, the green planet

Barely visible to the unaided eye on very dark, clear nights, the planet Uranus — currently shining at magnitude 5.7 — is now visible during the evening hours among the stars of the constellation Pisces, the fishes. Pisces is shaped like two fishing lines tied together in a knot, with one fish dangling from each line; it resembles the shape of the letter V, tilted on its side. The star that marks the knot is known as Al Risha, a fourth-magnitude star. Above Al Risha is a star of similar brightness, known as Omicron Piscium.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The next step is to carefully study a star chart, then scan that region with binoculars. Uranus should be evident, set off by its greenish tint. Uranus just passed its opposition to the sun (on Oct. 19) and is currently visible in the sky all through the night. Right now, it appears at its highest at around midnight local daylight time, when it will stand roughly 60 degrees above the southern horizon; roughly two-thirds up from the horizon to the point directly overhead (the zenith).

Using a magnification of 150x with a telescope of at least three-inch aperture, you just might be able to resolve Uranus into a tiny, pale-green, featureless disk. While observing Uranus from the Susan F. Rose Observatory at the Custer Institute in Southold on Oct. 21, New York amateur astronomer Bart Fried wrote to New York's Amateur Observers' Society (NYAOS): "[At] 180-power for Uranus ... that's a speck!" Unless the seeing, or blurring and twinkling caused by Earth's atmosphere is "total chaos," Fried suggested trying a 300x telescope, "and next time, it will actually look like a planet. And maybe with [a larger aperture], some mottling or cloud feature will be visible."

Indeed, larger instruments will better resolve this planet's verdant disk.

Uranus currently is 1.85 billion miles (2.97 billion kilometers) from the sun and 1.76 billion miles (2.83 billion km) from Earth. It has a diameter of 31,518 miles (50,712 km), and according to flyby magnetic data from Voyager 2 in January 1986, it has a rotation period of 17.4 hours.

At last count, Uranus has 27 moons. They are all in orbits that lie in the planet's equator, in which there is also a complex of nine narrow, nearly opaque rings, which were discovered in 1978. Uranus likely has a rocky core surrounded by a liquid mantle of water, methane and ammonia, encased in an atmosphere of hydrogen and helium.

A bizarre feature is how far over Uranus is tipped. Its north pole lies 98 degrees from being directly up and down to its orbit plane. Thus, its seasons are extreme: When the sun rises at its north pole, it stays up for 42 Earth years; then it sets, and the North Pole is in darkness for 42 Earth years.

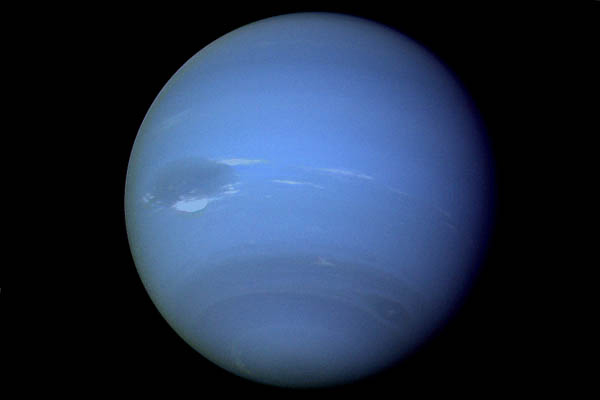

Neptune, the blue planet

Neptune, on the other hand, is much too faint to be perceived with the unaided eye. With Pluto's demotion to dwarf planet status in 2006, Neptune is now recognized as the most distant planet in the solar system. Currently, it lies at a distance of 2.78 billion miles (4.48 billion km) from the sun and 2.73 billion miles (4.39 billion km) from Earth.

It is slightly smaller than Uranus, with a diameter of 30,598 miles (49,232 km). Currently at magnitude 7.8, it's more than six times dimmer than Uranus. At this moment in time, Neptune can be found in the constellation of Aquarius, the Water Carrier.

You might try using the 3.7-magnitude star Lambda Aquarii to steer you toward Neptune. Currently, Neptune is only about a half-degree (about a full moon's width) to the south of this star. Neptune should be recognizable, thanks to its bluish color. If you have access to a dark, clear sky and carefully examine a star chart of this region, you should have no trouble in finding it with a good pair of binoculars.

From Long Beach, New York, amateur astronomer Larry Gerstman wrote to NYAOS: "For the last couple of months I have been following the motion of the planet Neptune in several of my binoculars. Its motion is like watching that of an asteroid, and much of the apparent motion is really more about the motion of the Earth. I have been using mostly my 20x60 Bushnell binoculars, which I just took out of my closet after many years of non-use since I have larger pairs, but I'm rediscovering how great they are — especially with their wide apparent field of 70-degrees (which is an actual field of 3.5-degrees at 20x) and crisp sharpness in a compact size."

Neptune is currently at its highest point in the sky at around 9 p.m. local daylight time, climbing about 40 degrees above the southern horizon; nearly halfway from the horizon to the zenith. [How to Measure Distances in the Night Sky]

With a telescope, trying to resolve Neptune into a disk will be more difficult for observers to do than it will be with Uranus. You're going to need at least an 8-inch telescope with a magnification of no less than 200x, just to turn Neptune into a tiny blue dot of light.

One of Neptune's 14 moons, Triton, has a tenuous atmosphere of nitrogen, and at 1,680 miles (2,703 km) in diameter, it's larger than Pluto. Because it is moving in a retrograde (backward) orbit, there has been some suggestion that Neptune's strong gravitational pull may actually have captured it in the distant past. Those who have access to a large telescope of 12 inches or more might even be able to get a glimpse of Triton, very close to Neptune itself.

Voyager 2 passed Neptune in August 1989 and relayed its possession of a deep-blue atmosphere, with rapidly moving wisps of white clouds. Also evident was a Great Dark Spot, rather similar in nature to Jupiter's famous Great Red Spot. Observations of Neptune using the Hubble Space Telescope suggest that the dark spot seen by Voyager 2 has dissipated; yet it has apparently been replaced by another. The atmosphere of Neptune is apparently chiefly composed of hydrocarbon compounds. Based on the rotation rate of its magnetic field, a rotation rate of 16.1 hours has been assigned to Neptune. Voyager 2 also revealed the existence of at least three rings around Neptune, composed of very fine particles.

Editor's note: If you take an amazing photo of Uranus or Neptune that you'd like to share with Space.com and our news partners for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Fios1 News in Rye Brook, NY. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.