Catch Flurry of Meteor Showers with Mobile Apps

The biggest meteor shower of the year, the Perseid shower, happens every August, but October brings skywatchers the first in a series of showers occurring from now until January.

The longer nights of fall and winter provide more observing time, too. Moonlight can make or break a meteor shower, and knowing where and when to look makes a difference, too. A few handy apps can help you prepare for these events.

In this edition of mobile astronomy, we'll focus on meteors and how you can use mobile apps to predict the best showers, see them for yourself and even contribute some citizen science by reporting your sightings. [Moon Phases and 3 Meteor Showers in Oct. 2016 (Skywatching Video)]

Meteor shower basics

Meteor showers are annual events that occur when the Earth's orbit carries the planet through zones of debris left in interplanetary space by multiple passes of periodic comets. (It's analogous to the material tossed out of a dump truck as it rattles along. The roadway gets pretty dirty if the truck drives the same route a number of times!)

Over centuries, or longer, the dust-size and sand-size (sometimes larger) particles accumulate and spread out into a cloud. As the Earth encounters the particles, the planet's gravity catches some, which burn up as "shooting stars" while falling through the atmosphere at speeds on the order of 125,000 mph (200,000 km/h).

The duration of a meteor shower depends on the width of the zone — that is, how many days or hours it takes Earth to pass through it. A meteor shower commences on the particular date when the Earth first enters the debris field. The shower then builds to a peak on the evening on which Earth passes through the densest portion of the cloud, and then tapers off to nothing on the date when the planet departs that region of space. Since the Earth returns to the same location in the solar system on the same date every year, meteor showers are annual events occurring on the same dates.

The number of meteors that skywatchers can see depends on whether Earth passes through the densest region, or merely skirts the edges. The brightness of the meteors is dictated by the average size of the grains in the cloud. Some showers are known for having fewer, but brighter meteors, while others are dimmer, but much more prolific. Most showers are global events, but certain showers are better for observers in the Northern or Southern Hemisphere due to the Earth riding high or low through the cloud.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

What's in a name?

Many people use the phrase "shooting star," but that's misleading. The source material is right here at home in this solar system, completely independent of the distant background stars, and the flash of light is occurring in Earth's atmosphere. The term "meteor" is used for the streak of light across the sky.

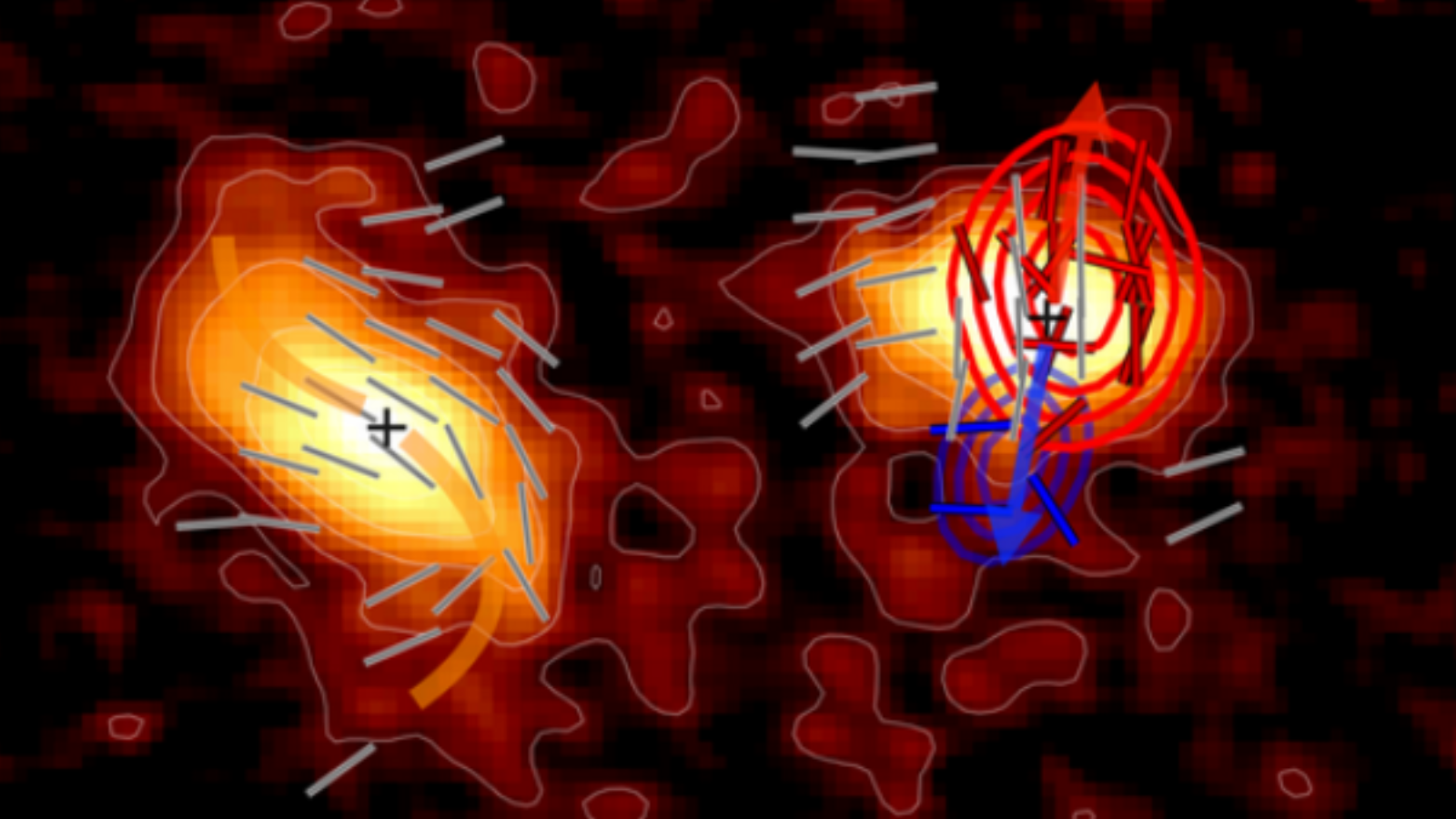

The bright light viewers see comes from a combination of factors. Red light is emitted by glowing molecules as the air is heated to a plasma by friction. Meteor material itself is being burned up during its high-speed passage. Oranges, yellows, blues, greens and violets are produced when minerals — such as sodium, iron and magnesium — in the dust particles are vaporized. Scientists can analyze the spectrum of color in a meteor trail and determine the composition of the material. If anything survives to land on the ground, it becomes a meteorite. An easy way to remember the difference is to recall that many rock names end with "ite," like granite.

How and when to see meteors

During a shower, meteors can appear anywhere in the sky, but they'll all be traveling away from a particular part of the sky called the radiant, and that always lies within the constellation that gives the shower its name: Orion for the Orionids, Perseus for the Perseids and so on. The radiant simply marks the direction in the sky that the Earth is heading toward while the planet is traversing the debris cloud. (This rule can be broken when two showers are underway at the same time, and by random meteors, called sporadics, which aren't part of the main debris field.) [Perseid Meteor Shower 2016: Amazing Photos by Skywatchers (Gallery)]

Throughout the shower period, the best time to see meteors occurs when the sky overhead is plowing straight into the debris field, like bugs splatting on a moving car's windshield. That's because, when the radiant constellation is overhead, the entire sky is available for observing. When a radiant lies near the horizon, the Earth will hide up to half the meteors. A common term used to rate the activity of a meteor shower is its ZHR, or zenith hourly rate. This is the estimated number of meteors you'll see in 1 hour when the radiant is overhead. It's based upon historical reports and computer models.

Try to find a dark viewing location that has as much open sky as possible. You can start watching as soon as it's dark. Don't worry about watching the radiant. Bring a blanket and a chaise to avoid neck strain. And remember that binoculars and telescopes will not help: Their field of view is too narrow.

SkySafari 5 and other sky-charting apps allow you to search for meteor showers by name, and will display the radiant location on the sky. The app provides information about the source comet; the start, end and peak dates; and some history. You can adjust the displayed time to show when the radiant is above the horizon for your location.

Because most meteors are quite dim, a dark sky is essential to see them. Unfortunately, the moon can ruin an otherwise terrific show. The new-moon phase, when the moon is near the sun, leaves the night sky dark. First-quarter moons set in early evening, and last-quarter moons don't rise until the wee hours, so skywatchers can work around them. Full moons stay up all night and can completely spoil a shower. Thankfully, phases of the moon vary year over year, so every shower gets good years and bad. Your astronomy app will tell you the phase of the moon at the peak of the meteor shower. Take a look at all the evenings around the peak to find evenings when the moon is less of a factor.

Some upcoming showers

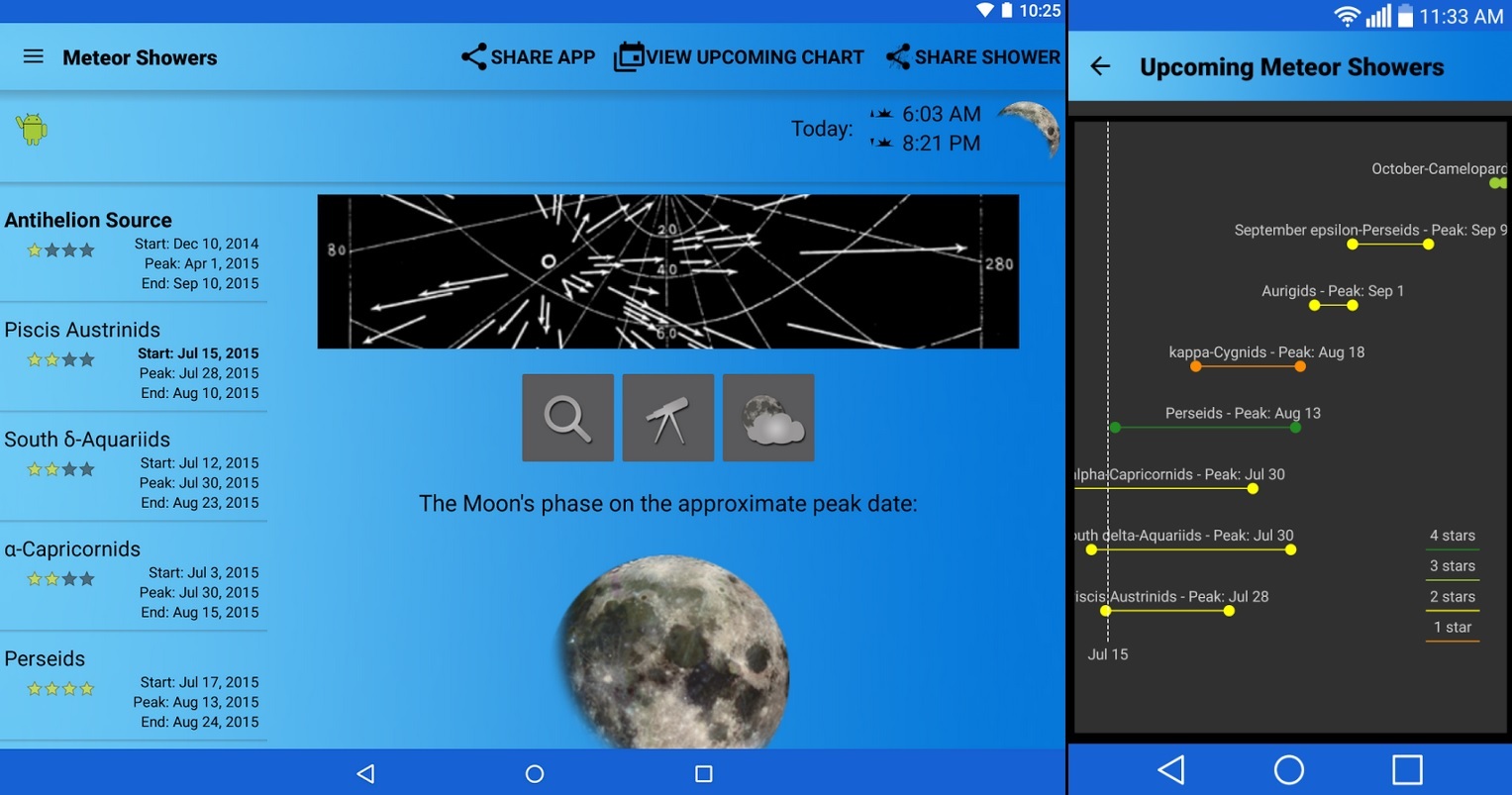

Here are some upcoming meteor showers to get you started, and a table of some others to mark on your calendar. You can also use dedicated apps to follow meteors. The free Meteor Shower Calendar app for Android and iOS issues notifications of upcoming showers and includes weather forecasts, moon phases and historical data.

The Draconid meteor shower is active from Oct. 5 to Oct. 9 this year, with the peak occurring on Saturday (Oct. 8). The radiant lies in southeastern Draco, the dragon, very close to a faint star known as Kuma (Nu Draconis). The material comes from the periodic comet 21P/Giacobini-Zinner. This shower is not very prolific, but sometimes produces a nice show. The following night is the peak of the Southern Taurids shower, caused by Comet Encke. This shower's radiant is southeast of Pisces, the fishes. This, too, is a modest shower, at three meteors per hour. During the peak nights this year, the moon is near first quarter and sets around midnight.

The Orionid meteor shower is most active between Oct. 4 and Nov. 14, and peaks after midnight on Oct. 21. Unfortunately, this year the moon will be near last quarter around the peak evenings and will be sitting near the radiant. Orionid meteors are debris left from long-ago passes of Halley's Comet. The radiant is above the bright red star Betelgeuse in Orion. Since Orion rises after midnight, your best bet is to look overhead in the wee hours. Orionids are known for being not too prolific (ZHR of 25), but bright. [Orionid Meteor Shower Photos of 2013 (Gallery)]

Perseids July 13 to Aug. 26 peak Aug. 11-12 ZHR 100

Leonids Nov. 17 to Nov. 30 peak Nov. 17-18 ZHR 15

Geminids Dec. 4 to Dec. 16 peak Dec. 13-14 ZHR 120

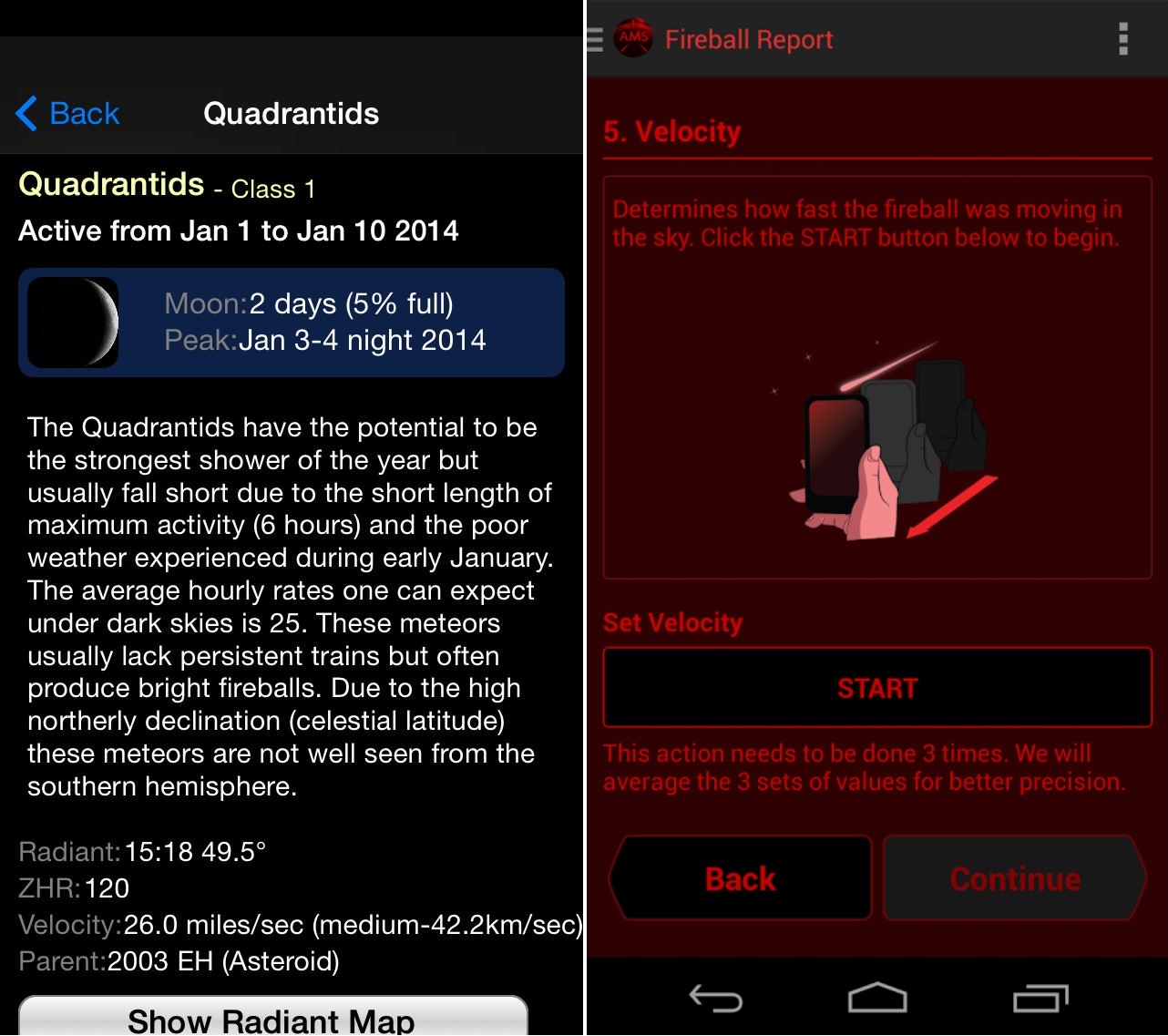

Quadrantids Jan. 1 to Jan. 10 peak Jan. 3-4 ZHR 120

Going beyond: Citizen science

An extremely bright meteor is referred to as a fireball, or bolide. Fireballs persist for many seconds, often spitting out fragments as they go, and sometimes leaving a vapor or smoke trail behind. If you spot one of these, chances are high that fragments of it will be found on the ground. A number of organizations have set up fireball-reporting websites that compare the sightings made by several people to triangulate where meteorite hunters should look. If you want to report your sighting, be sure to note the time it occurred, where you were, and the height and direction of travel. If enough observations from a single event are submitted, the errors are averaged out. [Fireball! Police Dash Cams Capture Meteor Streaking Over Northeast U.S. (Video)]

The American Meteor Society (AMS) is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1911 that focuses on all aspects of meteor-related science, including public education, scientific publication, and collection and tabulation of sighting reports. The AMS has a very extensive website where you can learn about meteors and report fireballs, or look up reports for one you may have witnessed. The group also offers the AMS Meteors app for Android and iOS, which allows you to check for current showers and capture a fireball sighting using gestures with your device!

The Fireballs in the Sky app for Android and iOS from the Curtin University of Technology in Australia provides plenty of meteor shower information and collects sighting reports used by scientists in the Desert Fireball Network. This fun app lets you build an animated virtual fireball that matches what you saw, and lets you replay it and submit your report.

Fresh meteorites, still containing interplanetary volatile gases and not yet contaminated by exposure to Earth's atmosphere and weather, are extremely valuable to scientists. If you find a fresh meteorite, avoid handling it, put it in an airtight container in your freezer, and contact your local university's geology department or natural history museum as soon as possible. The researchers will be extremely grateful!

In upcoming mobile astronomy columns, we'll review some new apps and gadgets, and tell you how to use astronomy apps in the classroom. Send me your suggestions! In the meantime, keep looking up!

Editor's note: Chris Vaughan is an astronomy public outreach and education specialist, and operator of the historic 1.88-meter David Dunlap Observatory telescope. You can reach him via email, and follow him on Twitter as @astrogeoguy, as well as on Facebook and Tumblr.

This article was provided by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of the SkySafari app for Android and iOS. Follow SkySafari on Twitter @SkySafariAstro. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Chris Vaughan, aka @astrogeoguy, is an award-winning astronomer and Earth scientist with Astrogeo.ca, based near Toronto, Canada. He is a member of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada and hosts their Insider's Guide to the Galaxy webcasts on YouTube. An avid visual astronomer, Chris operates the historic 74˝ telescope at the David Dunlap Observatory. He frequently organizes local star parties and solar astronomy sessions, and regularly delivers presentations about astronomy and Earth and planetary science, to students and the public in his Digital Starlab portable planetarium. His weekly Astronomy Skylights blog at www.AstroGeo.ca is enjoyed by readers worldwide. He is a regular contributor to SkyNews magazine, writes the monthly Night Sky Calendar for Space.com in cooperation with Simulation Curriculum, the creators of Starry Night and SkySafari, and content for several popular astronomy apps. His book "110 Things to See with a Telescope", was released in 2021.