Private Spaceflight Symposium Gets Update on Colorado Spaceport Plans

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

LAS CRUCES, New Mexico – Members of the international spaceflight industry gathered in New Mexico for an annual meeting to discuss new developments, ideas and technologies.

The International Symposium for Personal and Commercial Spaceflight began here yesterday (Oct. 7) iand continues through today. According to the ISPCS curator, Pat Hynes, the two-day meeting is a "live update of what's happening in the [spaceflight] industry — a snapshot at the time of the conference."

Among the topics being discussed at this year's meeting is an update on the status of a proposed spaceport in Colorado. [6 Private Companies That Could Launch Humans Into Space]

Article continues belowSpaceport Colorado pushing toward FAA licensing

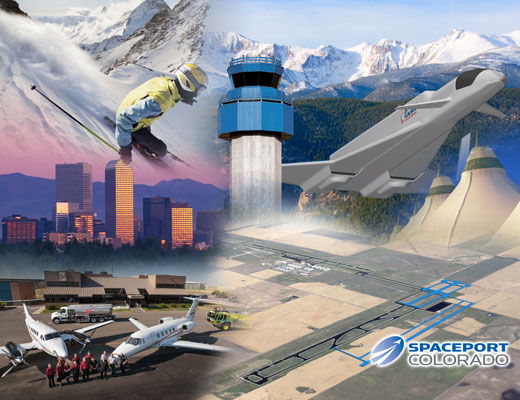

Spaceport Colorado, a facility about 6 miles from Denver International Airport, is getting ready to submit its application for a launch license from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The facility would service as a launch port for horizontal-launch space vehicles, including passenger space planes like Virgin Galactic's SpaceShipTwo and the XCOR Lynx. Spaceport Colorado would also provide a launch site for vehicles carrying small satellites, scientific experiments and other non-human cargo.

David E. Ruppel, airport director for Spaceport Colorado, told reporters that the spaceport expected to submit its application for a license sometime in the next few months. If all goes well, Ruppel says they can expect a decision by the second quarter of 2016. The spaceport does not have any specific customers lined up yet — Ruppel said those kinds of discussions will only start once a launch license is acquired.

Spaceport America, a licensed launch facility located about 90 miles north of El Paso, Texas, is also approved to launch large horizontal vehicles like the XCOR Lynx. Ruppel said both spaceports would have certain advantages, with Spaceport Colorado being very close to a major metropolitan area and international airport. This shortened travel time could be a major advantage for customers using commercial vehicles.

Staying in orbit

NASA has committed to keep its side of the International Space Station operating through 2024. But what will happen to the station when that contract expires, and how would the closure of the station affect the future of human spaceflight?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Former astronaut Chris Ferguson, who works in the commercial crew program at Boeing, made the argument that a crewed Earth-orbiting station is critical if humans ever hope to reach more ambitious space goals, like going to Mars or setting up a base on the moon.

"If Mars is [Mount] Everest, then a sustained [low-Earth orbit] presence is base camp," Ferguson said. "And as Megan Trainor said, 'It's all about the base." (Ferguson was making a play on the pop song by Trainor titled "All About That Bass." )

In his talk, Ferguson listed various technologies that have been developed on the ISS that would be crucial on a trip to Mars, like the water recycler that turns water vapor and urine into drinkable water for the astronauts. He also emphasized that astronauts need the opportunity to train in microgravity before they take a long, dangerous trip to Mars.

"The knowledge gained [on space missions] is perishable. The lessons learned, that we're learning today, quickly become diluted without constant reinforcement," Ferguson said.

If the private spaceflight industry isn't interested in sending people to Mars (yet), Ferguson said that the closure of the space station would remove a significant source of income for many major private spaceflight companies contracted to fly cargo and crew there.

Frank Culbertson, president of Orbital ATK's space system group, discussed a possible roadmap for gradually adding commercial elements to the space station's science facilities. In the short term, this could mean augmenting the current space station laboratory and making more room for commercial experiments, or even commercially owned scientific equipment. In the long term, it might mean building an entire commercial science module.

Culbertson noted that the commercialization of the ISS or the creation of a new, commercially owned low-Earth orbit station is not a new idea — but both he and Ferguson stressed that action should be taken soon to avoid a gap between the end of NASA's involvement with the station in 2024, and the next phase, whatever that may be. And while Ferguson said he felt that NASA would most likely need to be involved in developing a next phase, private industry could potentially be the initiator.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter