US Makes First Plutonium in 25 Years, for Spacecraft

The United States has begun producing plutonium-238 again for the first time in a quarter century, marking a key step toward averting a feared shortage of this important spacecraft fuel, NASA officials say.

The U.S. Department of Energy's plutonium reboot has not yet advanced beyond the test phase, but NASA is confident that production will eventually ramp up enough to power space probes for several decades to come.

"That's going to revive our supply and allow us to be able to complete a number of potential plutonium-necessary missions over this decade, and position us well into the decade after that," Jim Green, head of NASA's planetary science division, said Monday (March 18) at the 44th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in The Woodlands, Texas.

Plutonium-238 is not a bombmaking material, unlike its isotopic cousin plutonium-239. But Pu-238 is radioactive, emitting heat that can be converted to electricity using a device called a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG). [Nuclear Generators Power NASA Probes (Infographic)]

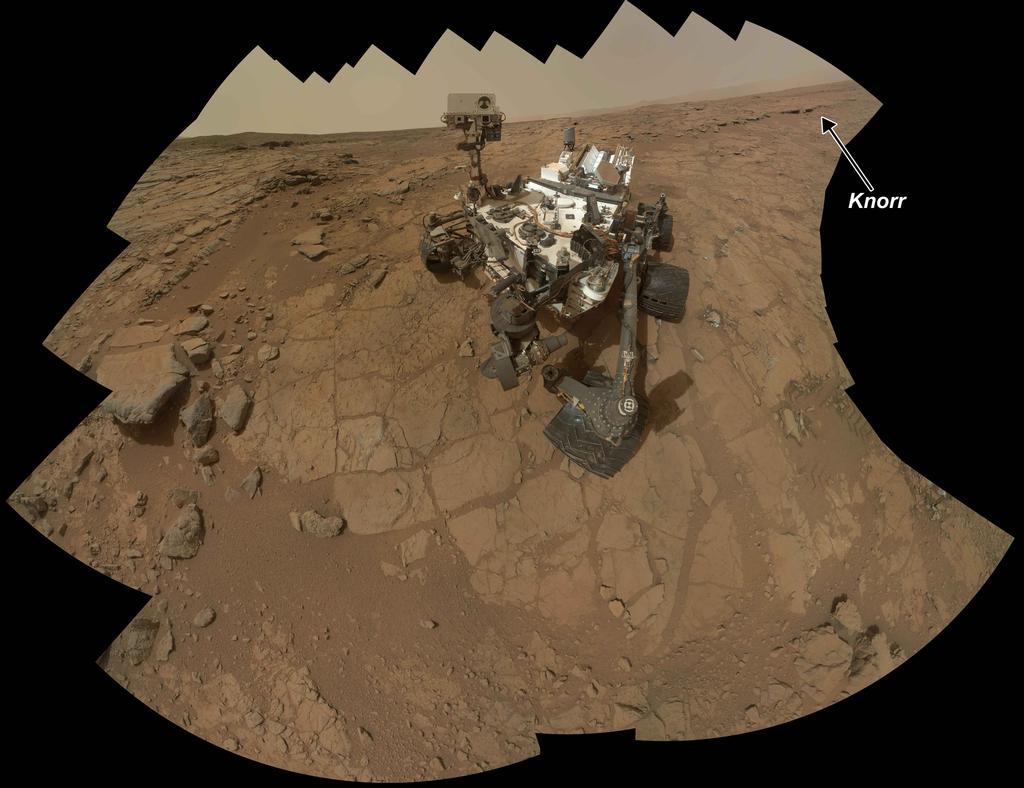

For decades, RTGs have been the power system of choice for NASA missions to destinations in deep space, where weak sunlight tends to make solar arrays impractical. For example, the agency's twin Voyager spacecraft, which are knocking on the door of interstellar space, both use RTGs, as does the car-size Mars rover Curiosity.

The Department of Energy (DOE) stopped producing plutonium-238 in 1988, after which time NASA began sourcing the material from Russia. But the space agency received its last Russian shipments in 2010, and its supplies have been dwindling ever since.

The DOE doesn't disclose the size of the nation's Pu-238 stockpile, but some scientists think it's alarmingly low. NASA officials have said the United States has enough of the stuff to power space missions through 2020 or so.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The DOE's Pu-238 restart could change those projections. At the agency's Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, engineers successfully produced small amounts of plutonium-238 by irradiating targets of neptunium-237 with neutrons, Green said.

While these activities were just a test, Green said the DOE should eventually be able to scale up plutonium-238 production to meet NASA's needs.

"We anticipate by the end of the calendar year that we'll have a complete plan from the Department of Energy — and not only a schedule, but costs — on how they'll be able to satisfy our requirement of 1.5 to 2 kilograms per year," Green said.

NASA and the DOE are also working together to develop a new power system called the Advanced Stirling Radioisotope Generator (ASRG), which will basically be a more efficient version of the trusty RTG.

Two flight-ready ASRGs should be completed by 2016, at which point NASA will put them into storage until selecting them for a mission, Green said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.