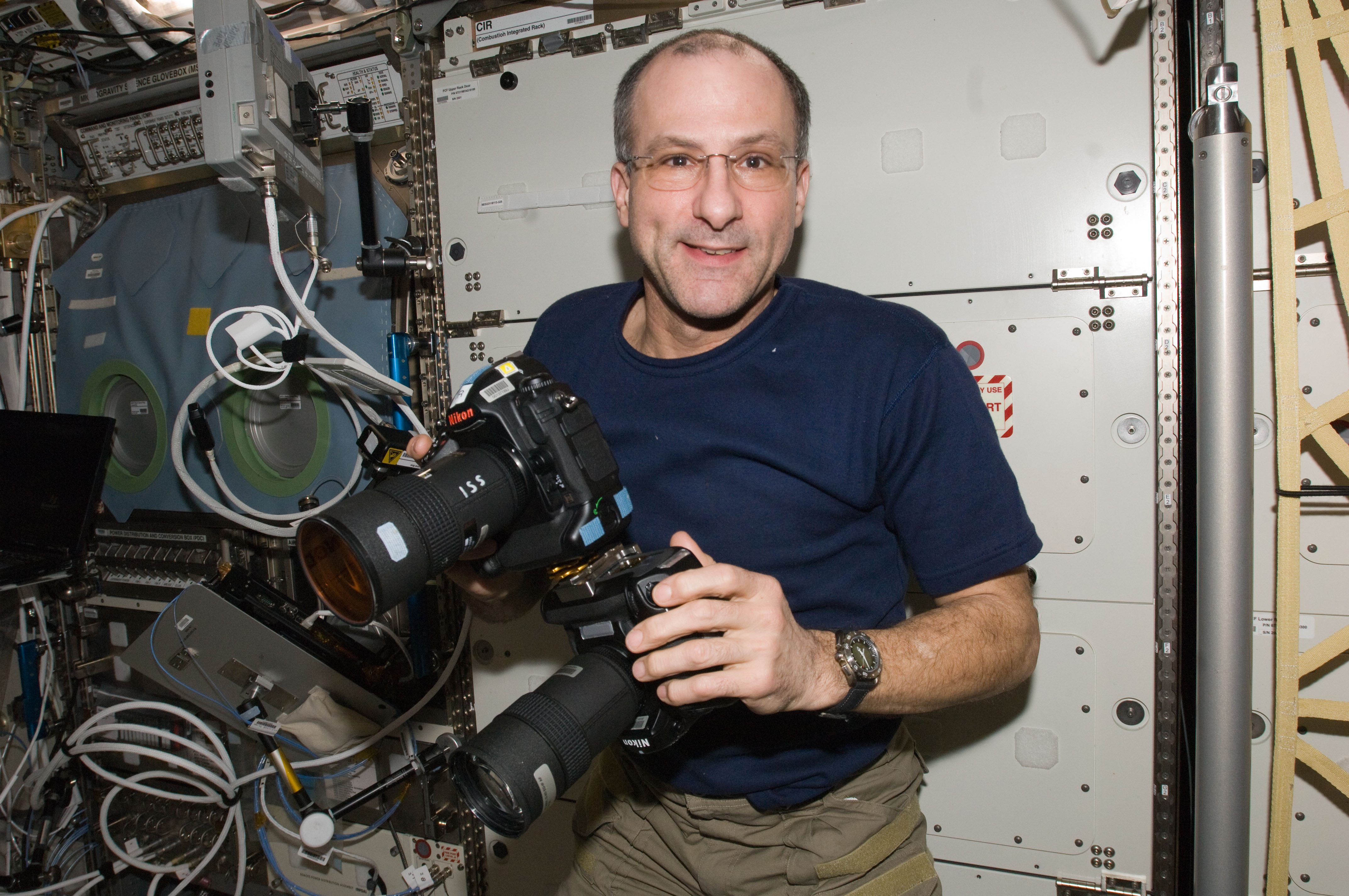

How to Live in Space: Astronaut Don Pettit Answers SPACE.com Reader Questions

NASA astronaut Don Pettit, who recently returned to Earth after a months-long stay at the International Space Station, answered some of your burning questions this morning (July 12) in a live satellite interview from the agency's Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Pettit and his two crewmates, Russian cosmonaut Oleg Kononenko and Dutch spaceflyer Andre Kuipers, landed on the steppes of Kazakhstan in Central Asia on July 1, after spending more than six months at the orbiting laboratory. The trio made up half of the station's Expedition 30 and 31 crews during their time in orbit.

As Pettit readjusts to life on Earth, he took some time Thursday to answer questions posed by SPACE.com readers. Here's what the veteran astronaut had to say about living in space, the most fascinating things he saw from his orbital perch, and what the International Space Station smells like.

SPACE.com: In space, when it’s so often dark outside, does your internal body clock get confused? (submitted by reader Gillian Finnerty)

Don Pettit: Actually, it does not. Your internal body clock seems to keep its own time. It has its own little mechanism, and you "wake up" in our morning, which is GMT time, and maybe it's sunny outside, maybe it's in the middle of a night pass, and you work through the whole day and you get hungry when it's about lunch time, and then at the end of the day, you start to get a little sleep-eyed. And by the time you're ready for bed, you just fall asleep. And that seems to be independent of the day-night cycles in terms of your orbit around Earth.

SPACE.com: What does the International Space Station smell like? (submitted by reader Sandy Hawkins)

Pettit: It smells like half machine-shop-engine-room-laboratory, and then when you're cooking dinner and you rip open a pouch of stew or something, you can smell a little roast beef. [Space Food Photos: What Astronauts Eat in Orbit]

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

SPACE.com: Do you think we can build greenhouses for food to live in space for long duration missions? (submitted by reader Joshua Michels)

Pettit: We can. And if you look at the energy balance and the volume and mass required to grow food, versus bringing it from Earth, I think for most of the food calories for the next series of explorations, you're better off to bring your major food calories from Earth in highly dense packages. But raising some food products, for just as condiments and as something to perk up the taste buds of the crew, that certainly has value-added. So I can see small aeroponic-type gardens, where crew will be raising things just to perk up their food a little bit.

SPACE.com: What kind of dreams do you have in space? Do they change in the microgravity environment? (submitted by reader Becky Graham)

Pettit: Well, dreams do change. When I'm on Earth, I dream about being in space, and when you're in space you dream about walking and being on Earth. And maybe it just figures that human beings are never satisfied with wherever they happen to be, which may be one of the reasons why we have the gumption to go off and explore in the first place.

SPACE.com: With over 300 days in space already under your belt, would you consider participating in a long duration mission, say to colonize another planet or moon? And what if there was a chance you couldn't return? (submitted by readers Tyler Crichton and William Stack)

Pettit: I would go back to space in a nanosecond — that's what I do for a living. Give me another couple of days here to get my feet on the ground, and I'm ready to go again. In terms of immigrating from Earth, I'd be willing to immigrate from Earth — immigrate into space, leaving Earth and never come back — so long as we had the technology so you could survive.

One-way missions to Mars where you go there and then run out of air and die, that's not in the cards. If you went to Mars, like people went from continental Europe to the New World in the 17th century, that model would be something I would do. I'd load my family up on the next rocket and we'd immigrate into space.

SPACE.com: What was the strangest or most fascinating thing you saw from the ISS – either in space or looking back at Earth? (submitted by readers Jay Lewis and Susan Cady)

Pettit: Well one of the most amazing things is to be able to see something like a comet from space. We saw a solar eclipse, and then the transit of Venus. So, there were a number of fairly rare, natural astronomical phenomenology that you can see from Earth, but when you see it from space, the vantage is slightly different and adds a new twist to it. And it allows you to see the physics of the situation. We see the shadow of the moon as it's cast, when it goes between Earth and the sun, and we call that an eclipse. And to see that shadow as a spot on Earth lets you know that, gosh, these guys that wrote the textbooks figured all of this out without seeing it from this viewpoint.

SPACE.com: How much micrometeoroid damage does the space station sustain on a yearly basis? And what do the astronauts feel or hear when something like that hits the station? (submitted by reader Joseph Fiet)

Pettit: Well fortunately we haven't been whacked by something big enough to do any real damage. The micrometeorites that do impact station, we can't hear them from the inside. They'll impact little structures and make little tiny divots, and we have micrometeorite shielding to protect the sensitive stuff — pressure halls and things like that.

You can see results of micrometeorite damage hitting things like hand rails and other pieces of equipment on the outside of station, and when we do a spacewalk, if we see something like that, we'll stop and take a picture of it so engineers on the ground can take a look at what's happening. And it's just something that's a continual occurrence. It's like a very small rain, a drizzle. It's just something you have to engineer around when you make a spacecraft.

Editor's note: Thank you to everyone who submitted questions for SPACE.com's interview with Don Pettit. Some of the selected questions were edited slightly for clarify, or to incorporate others that were similar. With so many great questions, we coudln't fit them all into the time available with Don, but we look forward to asking more reader questions in the future.

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.