Everyday Tech From Space: Cell Phone Cameras Have Space Origins

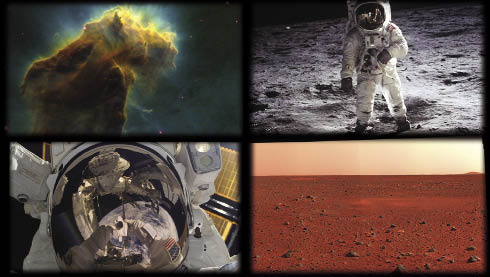

The iconic views of our universe provided by space telescopes like Hubble and cameras toted by Apollo astronauts on the surface of the moon have fueled scientific inquiry and inspired countless minds for decades. But the same technology that helped us see the vast plains of Mars and the brilliant, shimmering galaxies around us is also more prevalent in our everyday lives than you may think. In fact, one in every three cell phone cameras on the planet uses technology that was invented for NASA spacecraft.

The first digital camera may have been built in 1975 by Eastman Kodak – the photographic materials and equipment company – but the very concept of digital photography was developed in the 1960s by an engineer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in Pasadena, Calif.

At JPL, Eugene Lally investigated ways of using mosaic photosensors to digitize light signals that could then be used to capture still images. The idea spurred decades of research at NASA, as engineers sought ways to create small, lightweight image sensors that could withstand the harsh environments in space.

An image sensor contains photodetectors called pixels that collect photons, or single particles of light. Photons enter the pixel and are converted into electrons. This creates anelectrical signal that a processor then assembles into a still picture. It was a JPL engineer named Frederic Billingsley who first published the word "pixel" (short for "picture element"), in 1965.

In the 1990s, a team of researchers at JPL led by Eric Fossum studied ways to improve specific types of image sensors, called complementary metal-oxide semiconductor image sensors (CMOS), which would significantly miniaturize cameras onboard interplanetary spacecraft while maintaining high image quality for scientific purposes.

CMOS sensors, which are manufactured in the same way as microprocessors and other semiconductor devices, were easier to build and more cost-effective than the image sensors being used at the time. [10 Profound Innovations Ahead]

With their components and functions integrated onto a single chip, these new sensors also consumed as little as a hundredth of the others' power. This all meant that smaller cameras could be made at a lower cost without sacrificing state-of-the-art quality.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

At JPL, Fossum invented an active-pixel sensor, in which amplifiers within each pixel boost the electrical output generated by each collected photon, greatly improving image quality.

A series of miniature imaging system prototypes was created at JPL, and Fossum soon realized that the technology not only had broad applications in space but could be used to capture the marvels on Earth. In 1995, he presciently helped found a company called Photobit. Based in Pasadena, Photobit exclusively licensed the technology and became the first company to commercialize these new image sensors.

By June 2000, Photobit had shipped 1 million sensors for use in everything from digital cameras to dental radiography.

In 2001, Photobit was acquired by Micron Technology, a leading semiconductor company based in Boise, Idaho. Around this time, the popularity of cell phones with built-in cameras skyrocketed. The same technology that led to miniaturized cameras onboard NASA orbiters, landers and rovers proved ideal for integrating cameras into slimmer and slimmer cell phones that could capture crisp and vibrant images without hampering the phone's battery life.

The imaging group within Micron has since become Aptina Imaging Corp., now based in San Jose, Calif. In 2008 Aptina shipped its 1 billionth sensor.

Aptina's image sensors have led to advanced camera features such as tilt, zoom, electronic pan, motion detection, target tracking and image compression. The image sensor technology that had its roots at NASA is now used in one of every three cell phone cameras and is integrated into personal and notebook computer cameras worldwide.

The sensors also have found applications in the medical industry — in endoscopes and pill cameras — and in the automotive and surveillance industries. Rear-view cameras inside cars help motorists drive in reverse and park safely. Imaging technology is also used to develop network surveillance systems to catch intruders, and is used in many casinos to detect suspicious behavior.

More than 10 years since Photobit was founded, Aptina now often ships more than 1 million sensors in a day. As demand rises for improved cell phone cameras and high-end capabilities like HD imaging, this NASA-developed technology is likely to continue playing a significant role in everyday life.

You can follow SPACE.com Staff Writer Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.