Water Found in Tiny Dust Particles from Asteroid Itokawa

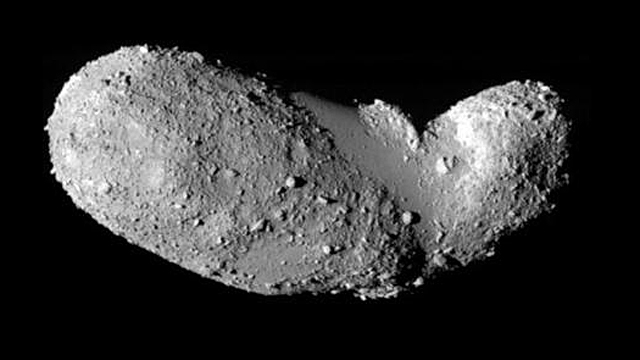

Japan's Hayabusa spacecraft brought the water-bearing asteroid dust to Earth in 2010.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Scientists have found traces of water in dust grains from the peanut-shaped asteroid Itokawa, and the discovery could shed light on how Earth got its water.

Researchers at Arizona State University (ASU) measured the water content in tiny particles of asteroid dust that were brought to Earth by Japan's Hayabusa spacecraft, which completed its sample-return mission in 2010. Although this isn't the first evidence of water on an asteroid, it is the first time that scientists have directly detected the water in a laboratory on Earth. Previous studies of water on asteroids have depended on data gathered by telescopes or instruments mounted on a spacecraft.

The first evidence of water on an asteroid was discovered in 2010, when astronomers using NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility in Hawaii spotted signatures of water ice and organic materials on asteroid Themis. Last December, NASA's OSIRIS-REx mission found hydrated minerals on asteroid Bennu while studying the space rock up close. Scientists now believe that water is common on asteroids in our solar system, whether it's in the form of water ice or hydrated minerals.

Article continues belowRelated: Hayabusa Asteroid Probe Returns to Earth (Gallery)

Based on their new findings, the ASU researchers suspect that S-type asteroids like Itokawa — stony asteroids made of silicates that are one of the most common types of space rocks in our solar system — could have delivered up to half of Earth's water supply early in our planet's formation history.

"We found the samples we examined were enriched in water compared to the average for inner solar system objects," Ziliang Jin, a cosmochemist at ASU's School of Earth and Space Exploration and lead author of the new study, said in a statement.

Jin and his co-author Maitrayee Bose, also a cosmochemist at ASU, measured not only the abundance of water in the samples, but also the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen — a chemical signature that can indicate an asteroid's origin and how similar its water is to the terrestrial water found on Earth. "The minerals have hydrogen isotopic compositions that are indistinguishable from Earth," Jin said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

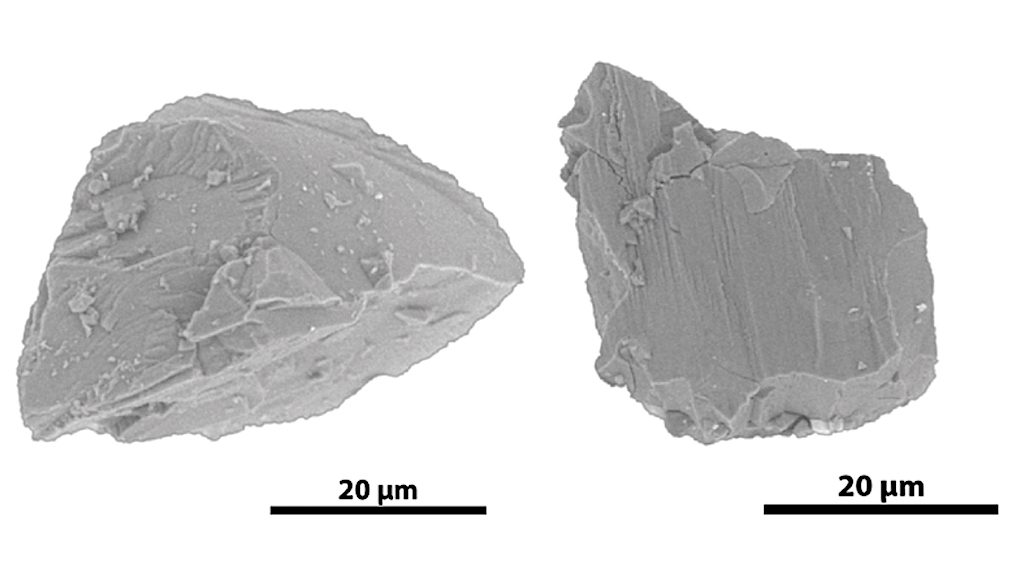

Of about 1,500 grains of dust that were contained in the sample from Hayabusa, the ASU team received five tiny particles, each about half the width of a human hair. Those particles come from the Moses Sea, a smooth and relatively featureless area near the middle of the peanut-shaped asteroid Itokawa.

Itokawa wasn't always shaped like a peanut; scientists believe that it was part of a larger parent body that broke apart some 1.5 billion years ago after a catastrophic impact with another space rock.

That parent body, which scientists think formed in the asteroid belt about 4.6 billion years ago, was about 12 miles (20 kilometers) wide before it was smashed to pieces. Some of the resulting rubble then clumped back together to form the "peanut," which is about 1,755 feet (535 meters) long and up to 1,000 feet (300 meters) wide.

For this study, they analyzed two of the particles from Hayabusa and determined that they contained rock-forming silicate minerals known as pyroxenes. Here on Earth, pyroxenes are known to contain water within their crystal structure. So, Jin and Bose thought the pyroxenes from Itokawa could contain water, too.

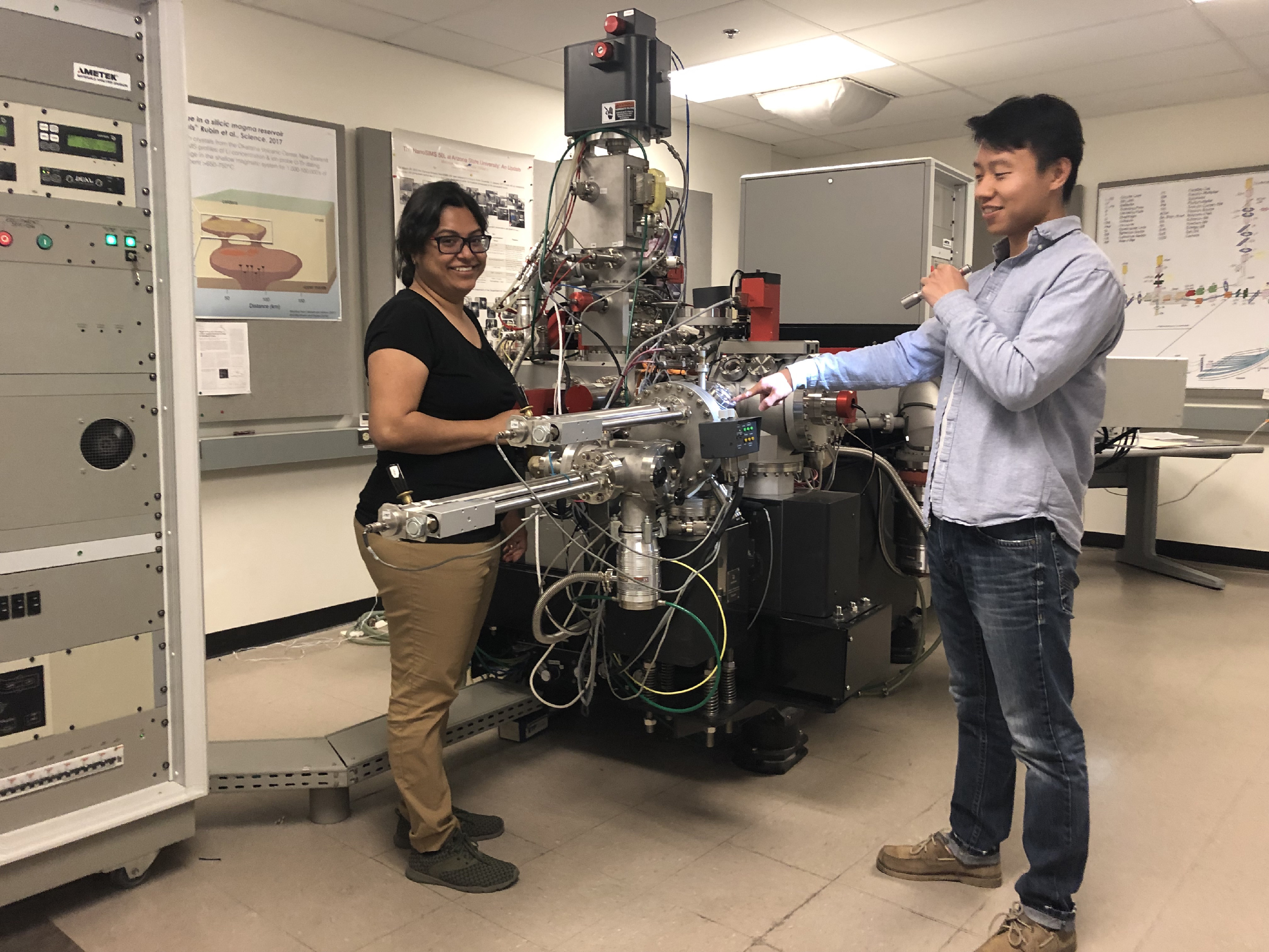

After the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) granted them the samples for this study, Jin and Bose used the Nanoscale Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometer (NanoSIMS) at ASU to measure the composition of the tiny particles.

They found Itokawa's samples to be "unexpectedly rich" with water, a discovery which they suggest could mean that "even nominally dry asteroids such as Itokawa may in fact harbor more water than scientists have assumed," ASU officials said in the statement.

The new study was published today (May 1) in the journal Science Advances.

- How Much Water May Be Tucked Away in Nearby Asteroids?

- Microscopic 'Speck' of Asteroid Dust Gets an Incredible Close-Up (Photo)

- In the Solar System: Water, Water Everywhere, But Where to Drink?

Email Hanneke Weitering at hweitering@space.com or follow her @hannekescience. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Hanneke Weitering is a multimedia journalist in the Pacific Northwest reporting on the future of aviation at FutureFlight.aero and Aviation International News and was previously the Editor for Spaceflight and Astronomy news here at Space.com. As an editor with over 10 years of experience in science journalism she has previously written for Scholastic Classroom Magazines, MedPage Today and The Joint Institute for Computational Sciences at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. After studying physics at the University of Tennessee in her hometown of Knoxville, she earned her graduate degree in Science, Health and Environmental Reporting (SHERP) from New York University. Hanneke joined the Space.com team in 2016 as a staff writer and producer, covering topics including spaceflight and astronomy. She currently lives in Seattle, home of the Space Needle, with her cat and two snakes. In her spare time, Hanneke enjoys exploring the Rocky Mountains, basking in nature and looking for dark skies to gaze at the cosmos.