Asteroid 2024 YR4 won't Earth but it could still ruin your day: Here's how

"The impact could pose some danger to equipment or astronauts on the moon, and certainly to satellites and other Earth-orbiting platforms, which are above our atmosphere."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

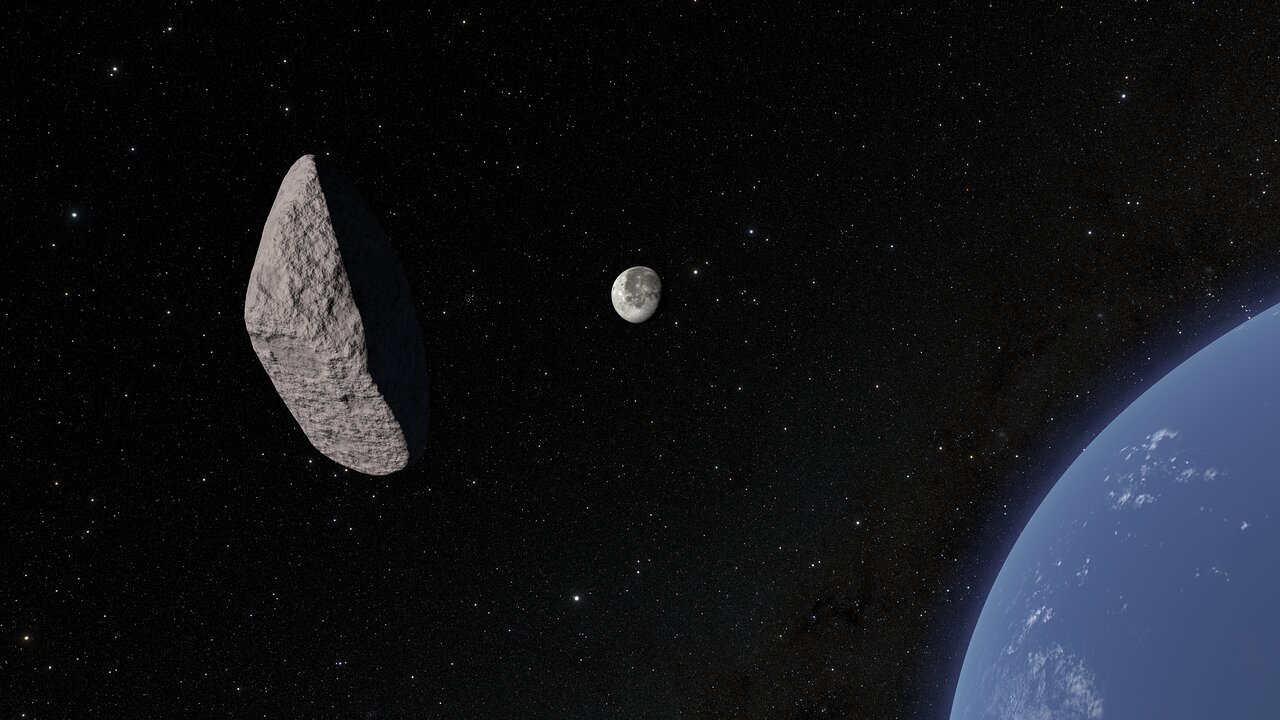

Earth may no longer be threatened by an impact from the asteroid 2024 YR4, but that doesn't mean this 200-foot-wide space rock can't still impact our lives.

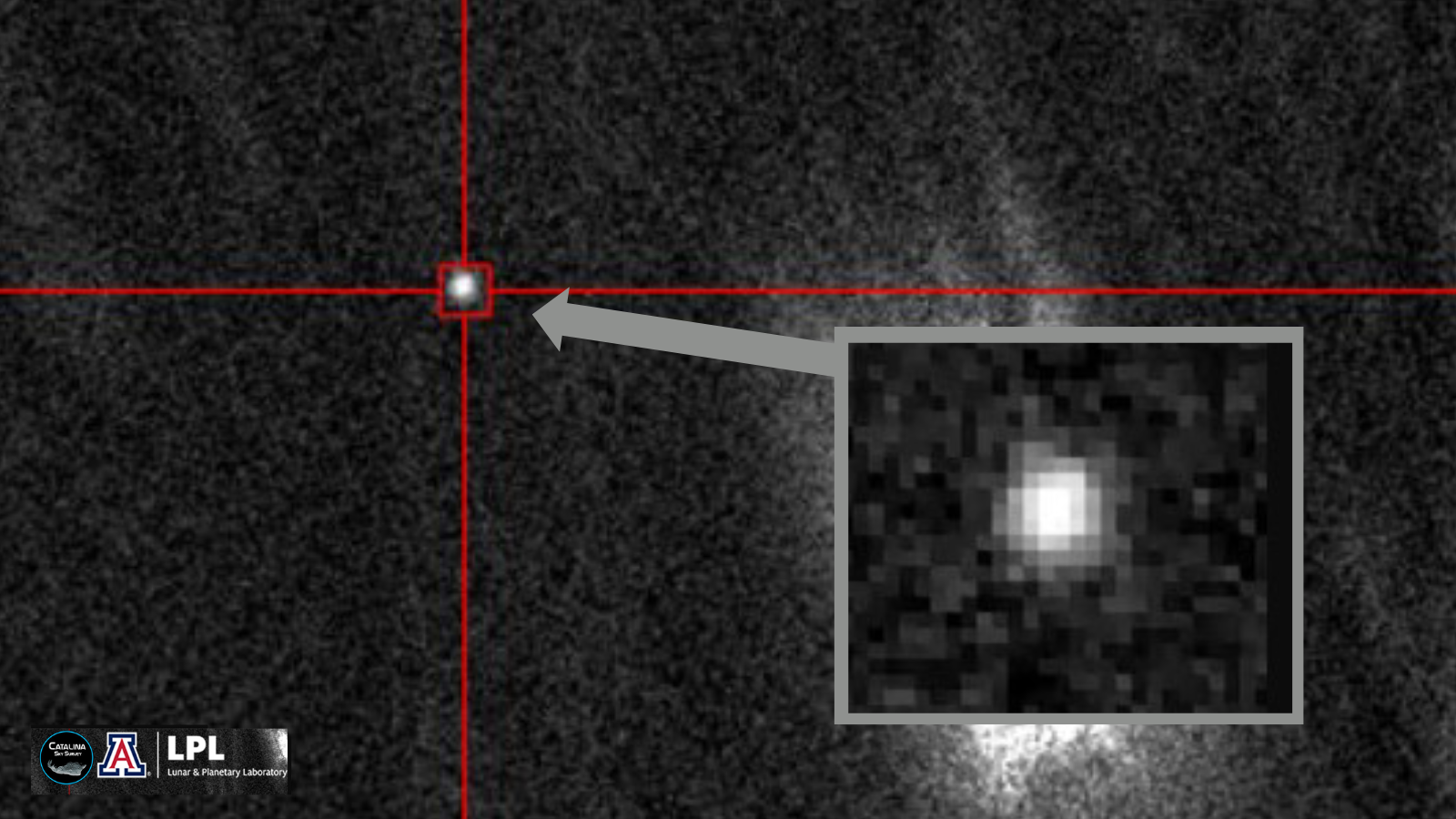

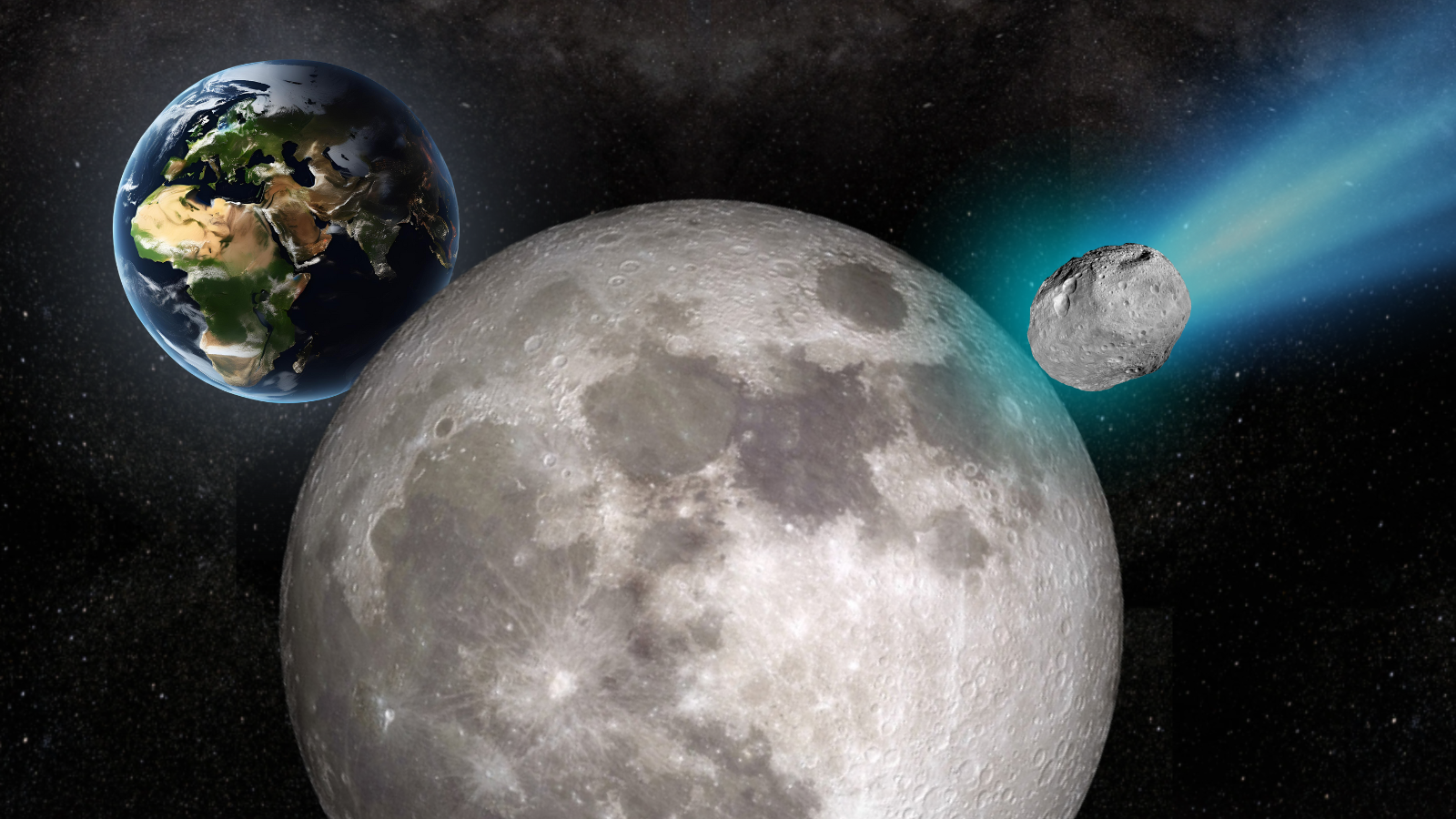

The asteroid, which at one point had a 1 in 43 chance of striking our planet, now has a 1 in 25 (4%) chance of hitting the moon in 2032.

New research suggests that if such an impact were to occur, ejecta blasted from the moon could damage satellites orbiting Earth. The resultant debris could also create a stunning meteor shower over Earth.

"A 2024 YR4 impact on the moon would pose no risk to anything on the surface of the Earth: our atmosphere will shield us," research author and University of Western Ontario astronomer Paul Wiegert told Space.com. "But the impact could pose some danger to equipment or astronauts (if any) on the moon, and certainly to satellites and other Earth-orbiting platforms, which are above our atmosphere."

What's the damage?

If 2024 YR4 were to strike the moon in 2032, it would be the largest lunar impact in approximately 5,000 years. Wiegert explained that the impact would release energy equivalent to the detonation of 6 million tons of TNT. That's comparable to the detonation of a large nuclear weapon.

For comparison, "Little Boy," the nuclear weapon that devastated Hiroshima, released an explosive yield equivalent to approximately 15,000 tons of TNT. Understandably, such a large blast on the lunar surface would create a lot of debris.

"The impact would excavate a crater about 0.62 miles (1 kilometer across)," Wiegert said. "Most of this material would fall back to the moon, but a small fraction, around 0.02% to 0.2%, could be ejected at high enough speeds to escape the moon."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Though that is just a small fraction of the total debris, it still equates to between 10 million and 100 million kilograms of lunar rock entering space.

"The YR4 impact, if it occurs and if it occurs in a favorable location, could produce a flux of meteoroids 10 to 1,000 times higher than the normal background for a few days," Wiegert said. "The debris would be travelling a bit slower than typical meteors, at around 22,400 miles per hour (10 km/s) rather than 44,700 to 67,100 mph (20 to 30 km/s), but this is still faster than most bullets."

In fact, that ejecta speed is about 11 times faster than a bullet fired by a rifle and 30 times as fast as a bullet from a handgun. That means these pieces of debris would have more than enough energy to damage satellites or other space-based technology.

To reach Earth-orbiting satellites, the debris would have to travel about 236,000 miles (380,000 km), meaning we would have hours to days of warning about the impending danger.

Fortunately, though this could disturb things here on the surface that rely on satellites, like communication, navigation, and weather monitoring, the direct risk is very low.

"The debris will burn up in Earth's atmosphere. We don't expect there to be many pieces large enough to survive passing through Earth's atmosphere," Wiegert said. "A rock would have to be 3.3 feet (1 meter) or more in diameter to survive entry, but we expect most of the debris to be inches or smaller."

Wiegert added that the impact of this debris to our immediete space enviroment could be long-lasting, lingering around Earth for years.

"We were surprised at how well material can be delivered to the Earth by this kind of impact, though it really depends on the asteroid impacting in a certain region of the moon, as impacts in other regions produce very little," he added.

So does the possible threat presented by 2024 YT4's potential impact on the moon warrant a new scale, similar to the Torino Scale (the method used to categorize the potential impact hazard of near-Earth objects like asteroids and comets)?

"No, the indirect consequences are too varied to compress into a single scale," Torino scale creator and planetary scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Richard P. Binzel told Space.com. "The Torino Scale is all about whether a passing asteroid merits attention in the first place, and of course, most asteroids don't."

Binzel added that probability is always the key element with asteroids and any risk they pose.

"What one can control, by obtaining more telescopic measurements, is determining with certainty whether you have a hit or miss. After all, at the end of the day, an object either hits or misses. The answer is deterministic," he continued. "As much as I would love to be a spectator watching those lunar fireworks, that is not the way to bet or something to get too concerned about.

"The only imperative that makes sense right now is to get the data and bring certainty to the question of hit or miss."

Whether 2024 YR4 impacts the moon or not, where this impact would occur on the lunar surface, and the risk that it poses to space-tech could be determined when the asteroid returns to Earth and becomes visible again in 2028.

"Now we wait. There is, as of right now, about a 4% chance of asteroid YR4 hitting the moon, and we probably won't get this number updated until the asteroid returns to visibility in 2028," Wiegert said. "At that point, we should know pretty quickly whether or not it will in fact hit the moon.

"The whole event would be exciting to watch in binoculars or a small telescope."

The team's research has been submitted for publication in the American Astronomical Society journals, and a preprint version is available on the repository website arXiv.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.