Watch balloon-like space station module explode (on purpose) during 1st full-scale burst test

It's the first full-scale test of Sierra Space's future space module.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

That's one big bang for space station safety.

Sierra Space deliberately blew up its first full-scale space station module prototype recently to get ready for future space missions that could take place as soon as 2030, the company announced on Monday (Jan. 22). The blast was equivalent to using 164 sticks of dynamite, officials said in an e-mailed statement to Space.com.

Sierra Space has been sending space equipment sky-high in a series of explosive tests at NASA's Marshall Space Center in Alabama, but all of the past testing was done on scale models.

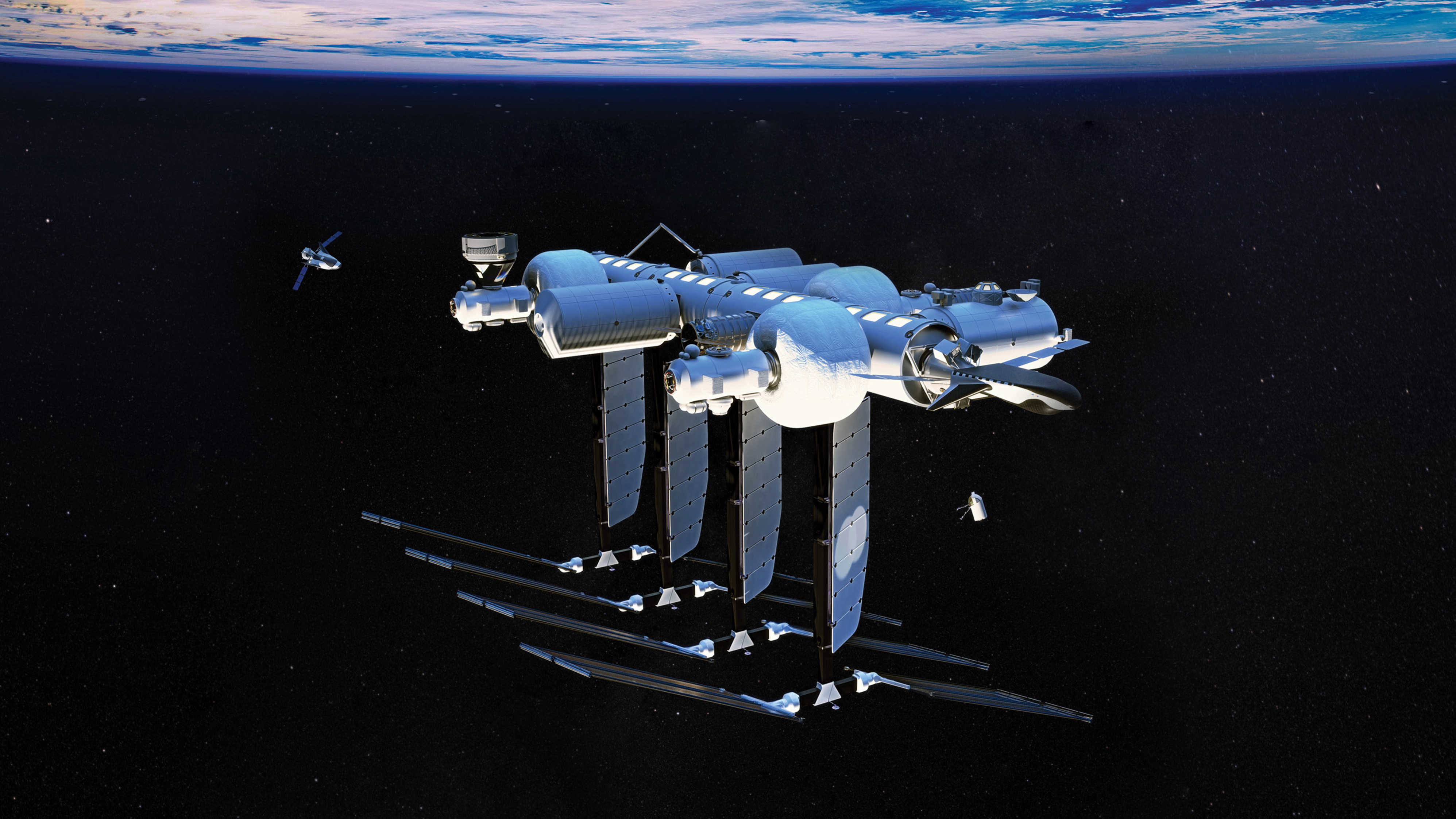

Article continues belowThe company's inflatable module type — which uses soft goods technology from ILC Dover, such as Vectran straps — will fly on the Sierra Space- and Blue Origin-led Orbital Reef space station. That's one of several concepts NASA has funded to replace the International Space Station (ISS) after the long-running, orbiting complex retires in 2030 or so.

Sierra Space says the dimensions of its modules are roughly equivalent to "an average family home," which, by U.S. Census 2022 numbers, would be 2,299 square feet or 213.5 square meters for single homes built that year. That said, Sierra Space officials work in cubic feet because microgravity allows for all parts of the space inside a room to be used. If you'd like to do the math yourself: the module is three stories (20.5 feet, or 6.2 meters) tall, with a diameter of 27 feet, or 8.3 meters, Sierra Space has stated.

Related: NASA looks to private outposts to build on International Space Station's legacy

Few inflatable modules have flown in space before, although they are no strangers to the ISS; for example, a module made by Bigelow Aerospace has been in testing for years there to evaluate how well it holds up to tough space conditions, such as radiation and microgravity.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

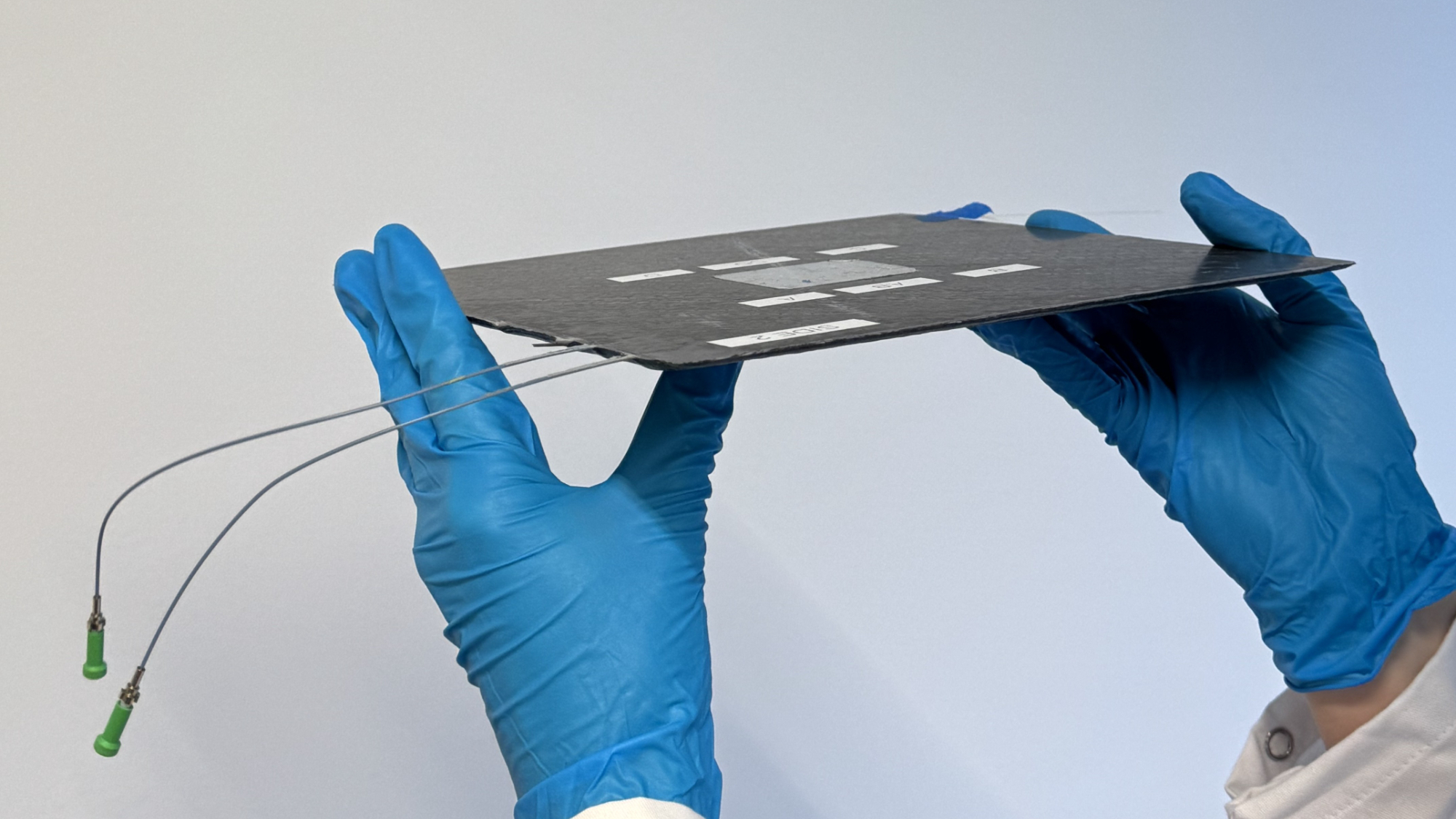

Sierra Space's Large Integrated Flexible Environment (LIFE) habitat prototype has been undergoing a series of "burst tests" that deliberately keep pumping air into the structure until it fails, ultimately popping apart like a balloon. In this test, the results exceeded NASA's safety requirements by 27 percent. In other words, it withstood a pressure of 77 pounds per square inch (psi) before bursting, which is well above the 60.8 psi agency guidance.

"We are driving the reinvention of the space station that will shape a new era of humanity's exploration, and discovery," Tom Vice, Sierra Space CEO, said in the statement. As justification, Vice highlighted the cost value of an inflatable module, citing its ability to crunch into a five-meter (60-foot) rocket. That'd mean it can save on packing space, and be more than lightweight enough for a launch into orbit.

In theory, LIFE could send up three of these modules to beat the equivalent size of the ISS. There are bigger versions forthcoming, too. One 50,000 cubic-foot (1,400 cubic-meter) design, for instance, could surpass the ISS's capacity in a single launch, according to Sierra Space.

Sierra Space aims to continue its burst tests using full-scale and scale modules, as well as test how the structure fares against micrometeorites. Although, how ready any concept could be to replace the ISS in six years is still, so to speak, up in the air.

Last year, NASA officials repeatedly emphasized that they are working to reduce any potential gap that may occur between stations as much as possible, considering the technological and funding challenges that arise in the inflationary environment we've been seeing and the 2024 election year. The White House also issued high-level guidance in March 2023 concerning how NASA will continue to attract research to commercial stations after the ISS program concludes.

Then. in October 2023, NASA opened a new solicitation asking for early industry "feedback on requirements for new commercial space stations," particularly in making clear the strict requirements of NASA's human rating standards for space vehicles.

That same month, NASA's Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel recommended the agency swiftly create a "comprehensive understanding" of what those human safety requirements would be, according to SpaceNews, per announcements given during the Oct. 26, 2023 public meeting in Washington, D.C.

David West, a member of the panel, called the 2030 timeline "very tight", and said industry would require a "clear, robust business case" for commercial stations to be able to fill the forthcoming low Earth orbit research gap.

NASA has funded space station design work now being undertaken by two commercial teams: one with Blue Origin and Sierra Space as co-leaders, and the other with Voyager Space. (Northrop Grumman announced Oct. 4 that it would switch its own, independent work initially funded by NASA in favor of joining with Voyager Space.)

Separately, NASA is also funding Axiom Space so the company can create commercial modules for the ISS itself. Late in the orbital complex's lifetime, Axiom plans to detach the modules as a united set, to create its own free-flying space station.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.