Boom! Watch an inflatable space station module explode on video

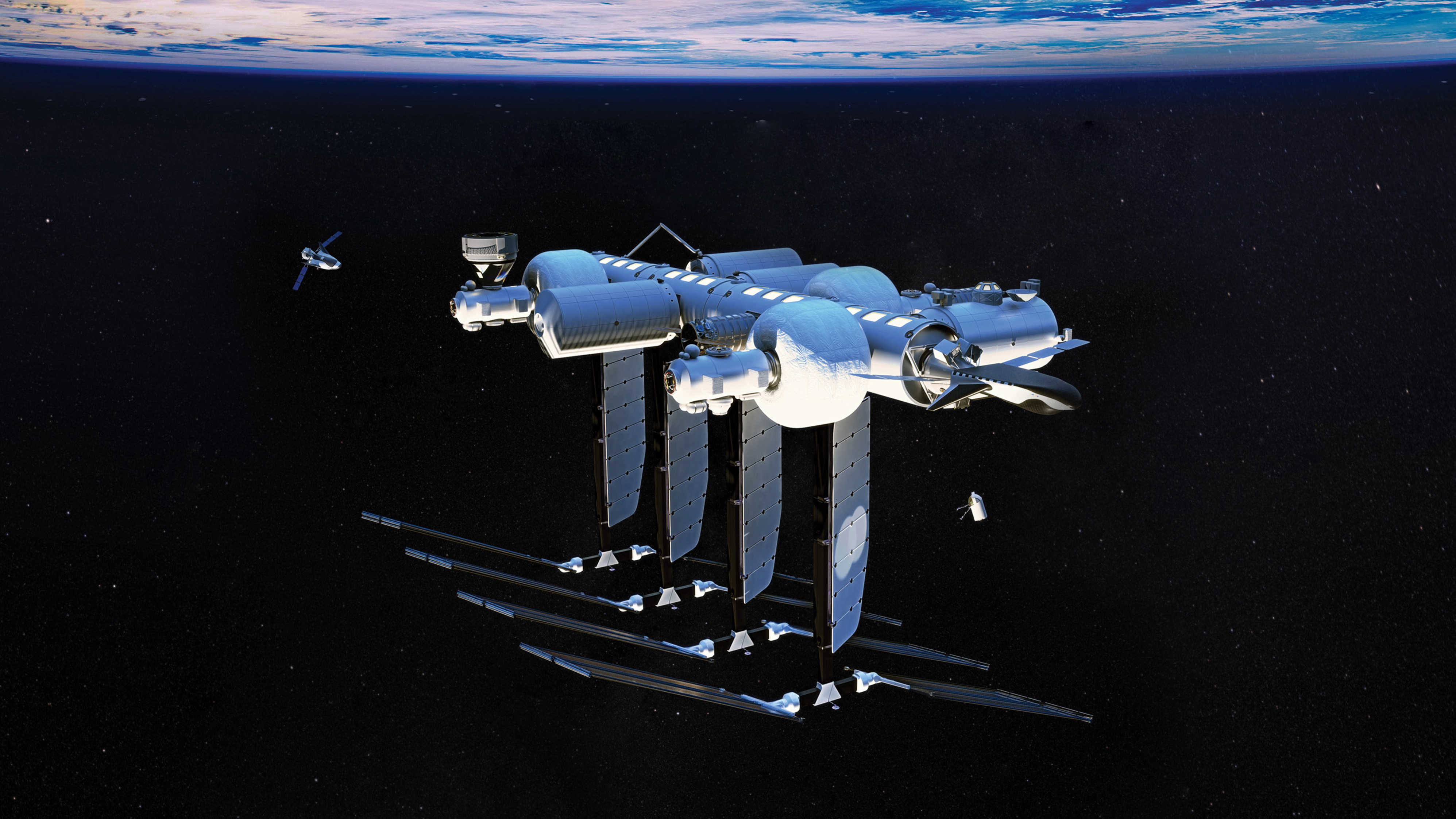

Sierra Space completed this test to prepare for Orbital Reef, a private space complex to replace the International Space Station.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

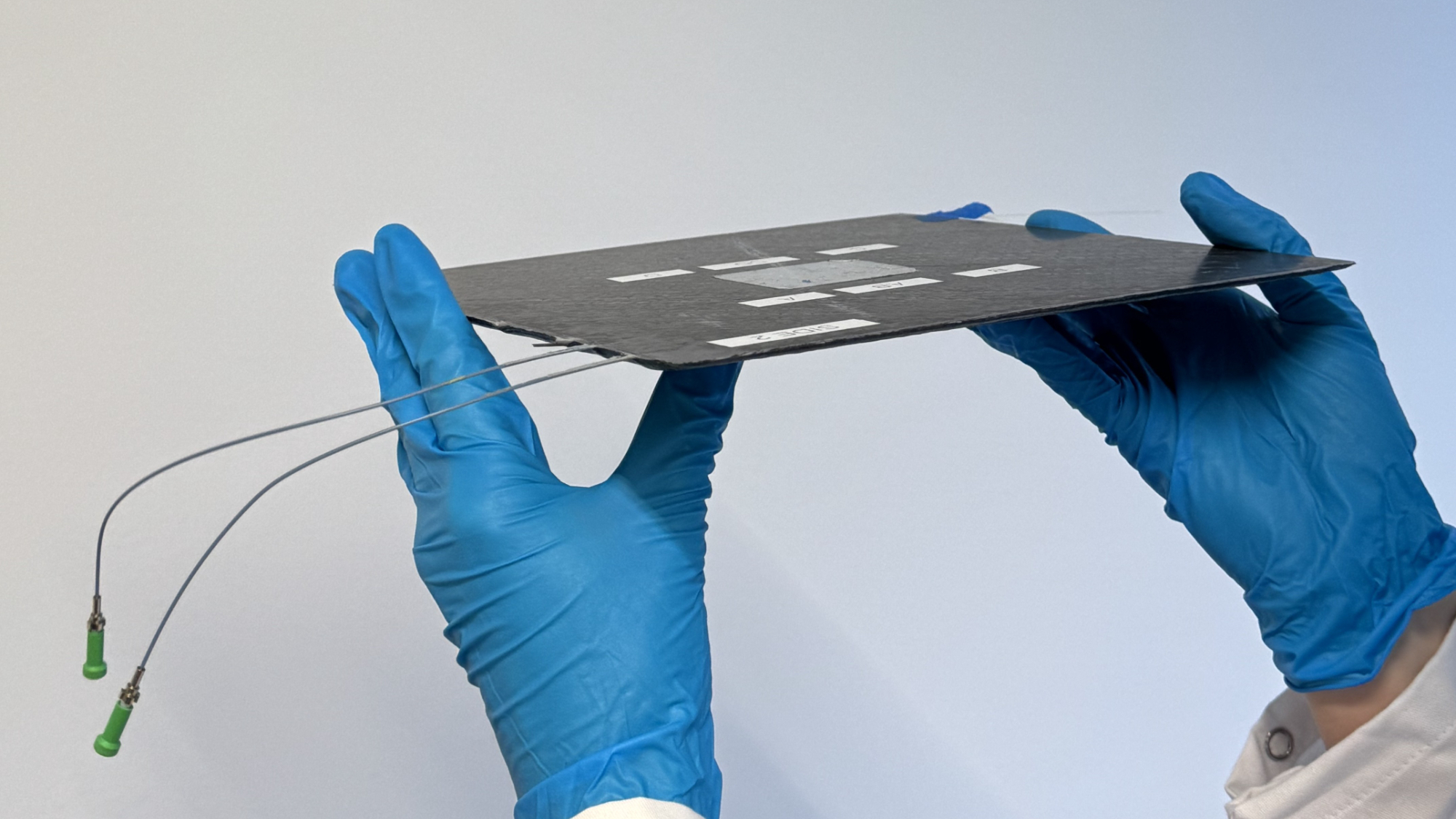

Sierra Space deliberately exploded a small prototype for an inflatable astronaut habitat to get ready for spaceflight.

The company conducted what it calls the "ultimate burst pressure test" (UBP) as it progresses along the long road to helping develop a private replacement to the International Space Station (ISS). The inflatable module, called Large Integrated Flexible Environment, or LIFE, will form part of the larger Orbital Reef space station led by Blue Origin. NASA seeks to replace the aging ISS in the 2030s with industry-led private stations, and Orbital Reef is among them.

The recent test was the second in 2022 to explode a Sierra Space module prototype for Orbital Reef, following a similar procedure in July. Simply put, by testing a smaller prototype of the module to its literal limit, engineers can make spaceflight safer for future astronauts.

Article continues below"This second successful UBP test proves we can demonstrate design, manufacturing and assembly repeatability, all of which are keys areas for certification," Shawn Buckley, Sierra Space's LIFE chief engineer and senior director of engineering, said in an e-mailed statement.

Related: NASA looks to private outposts to build on International Space Station's legacy

The Sierra Space team blew up the module on Nov. 15 inside the flame trench of a Saturn 1 and 1B test stand at the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, performing the burst test in the same area where NASA tested rockets for the Apollo moon program of the 1960s and 1970s.

NASA, past spacesuit maker ILC Dover and Sierra Space all worked together on the test. Analysis is ongoing, but early work shows that Sierra Space met its obligations for the test, according to the company.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

NASA tasked Sierra Space to blow up two prototype modules, which are smaller than those that will be used on Orbital Reef and had maximum burst pressures of 192 and 204 pounds per square inch (psi), respectively. Both modules easily held up past the safety requirement of 182.4 psi set by NASA in designing Orbital Reef.

In photos: Inside Sierra Nevada's inflatable space habitat for astronauts in lunar orbit

A year ago, NASA awarded $415 million split across three concepts for early private space station development. The money was split almost evenly among the three teams: the Orbital Reef team led by Blue Origin that includes Sierra Space received $130 million, Nanoracks LLC's team $160 million and Northrop Grumman Systems Corp.'s team $125.6 million.

Sierra Space plans to push forward on Orbital Reef development with Blue Origin in 2023 by doing burst tests on full-size prototypes. Sierra Space intends to use its Dream Chaser cargo plane and a future crewed version to bring astronauts and supplies to the private complex.

Inflatable modules are already being tested on the ISS by Bigelow Space. The Bigelow Expandable Activity Module, or BEAM, shipped to orbit in 2019; ISS astronauts periodically assess its performance in orbit against solar radiation and the vacuum of space.

Elizabeth Howell is the co-author of "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022; with Canadian astronaut Dave Williams), a book about space medicine. Follow her on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.