Inflatable Habitats: From the Space Station to the Moon and Mars?

The upcoming launch of a private inflatable module toward the International Space Station could help pave the way for colonies on the moon and Mars.

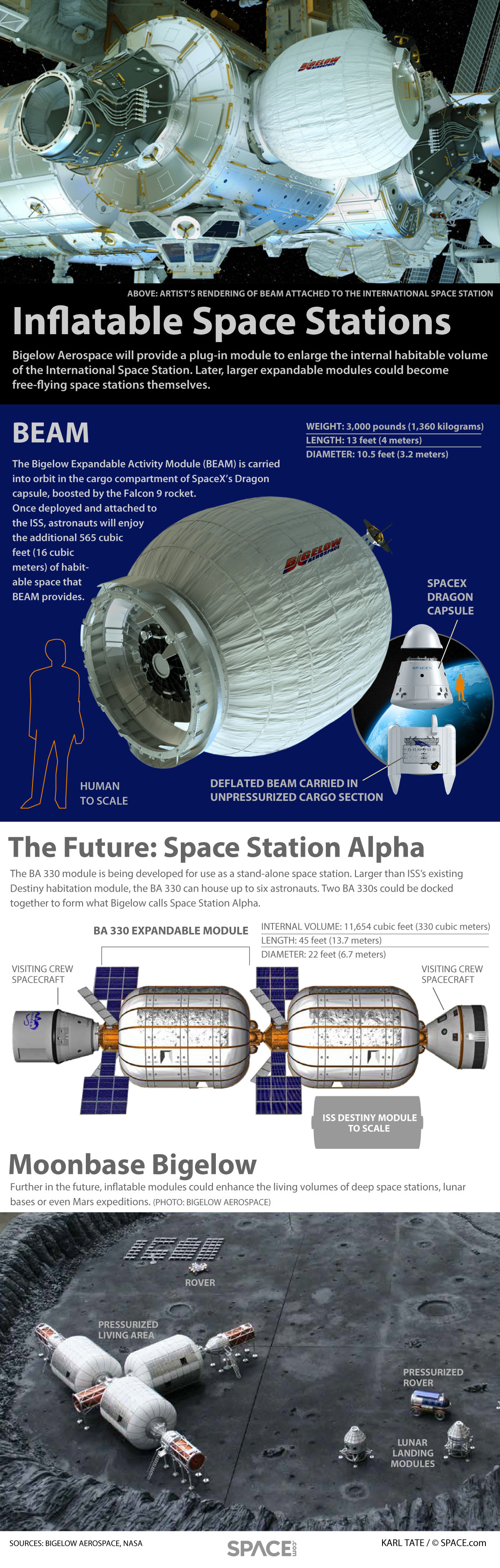

Bigelow Aerospace's Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM) will blast off on SpaceX's next robotic cargo mission to the space station for NASA. That flight was originally scheduled for September, but the disintegration of SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket during the company's last cargo run in late June will likely delay it.

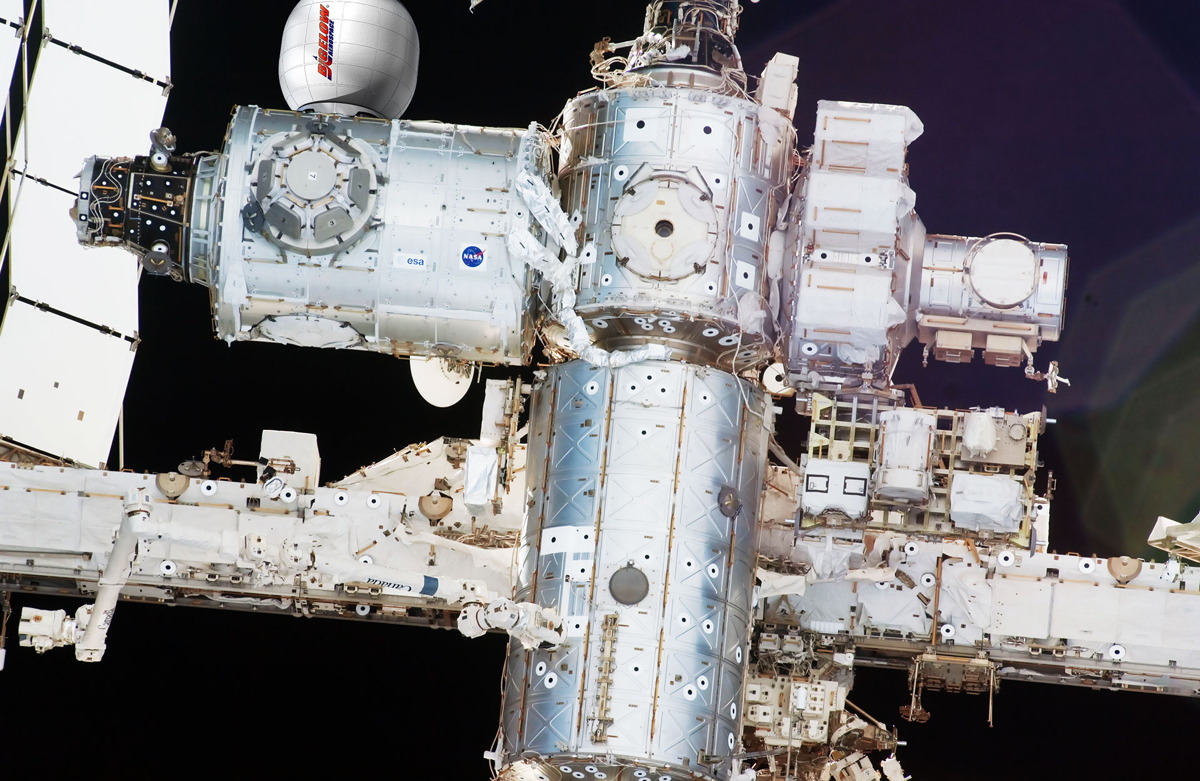

Whenever BEAM ends up reaching orbit, the module's addition to the International Space Station (ISS) will be a big milestone for inflatable spacecraft in general and Bigelow Aerospace in particular, company representatives said. [Bigelow's Inflatable Space Station Idea in Photos]

"This will give us the opportunity to demonstrate expandable-habitat technology as part of a crewed system for the very first time," said Michael Gold, director of Washington, D.C., operations and business growth for Bigelow Aerospace. "This will be a very big step."

The inflatable advantage

Inflatable habitats such as BEAM launch in a tightly packed configuration and then expand significantly when they get to space. Therefore, they take up less room in a rocket fairing than traditional metal habitats do and offer much more living space when they reach their destinations, advocates say.

Expandable spacecraft also offer greater protection against space radiation and debris strikes than metal modules do, Gold said. Indeed, he added, NASA recognized the potential of expandables for human spaceflight more than 50 years ago, even developing a model inflatable space station by the early 1960s.

But that early model was made of rubber — the contractor was Goodyear — and would almost certainly have been destroyed by any meteoroid or piece of space junk that hit it, Gold said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

So "the idea of inflatable or expandable habitats had to be shelved to allow the materials science to mature to the point that you had Kevlar-like weaves, or materials that were flexible yet strong enough to withstand the space environment," Gold said last month during a presentation with NASA's Future In-Space Operations working group.

NASA revived the idea of expandable habitats for the Space Exploration Initiative (SEI), a long-range plan announced by then-President George H. W. Bush in 1989, Gold said. SEI aimed to construct a space station, establish a permanent moon colony and, eventually, send astronauts to Mars. [5 Manned Mars Mission Ideas]

But SEI was dead four years later. NASA kept working on inflatables throughout the 1990s via its TransHab program — short for Transit Habitat, since the technology was envisioned as helping astronauts reach Mars — with the idea that expandables could still be incorporated into the ISS. In 2000, however, Congress explicitly prohibited NASA from continuing work on TransHab.

And that's when Bigelow Aerospace entered the picture. The Nevada-based company, founded in 1999 by hotel magnate Robert Bigelow, bought the rights to NASA's TransHab technology and continued to develop it.

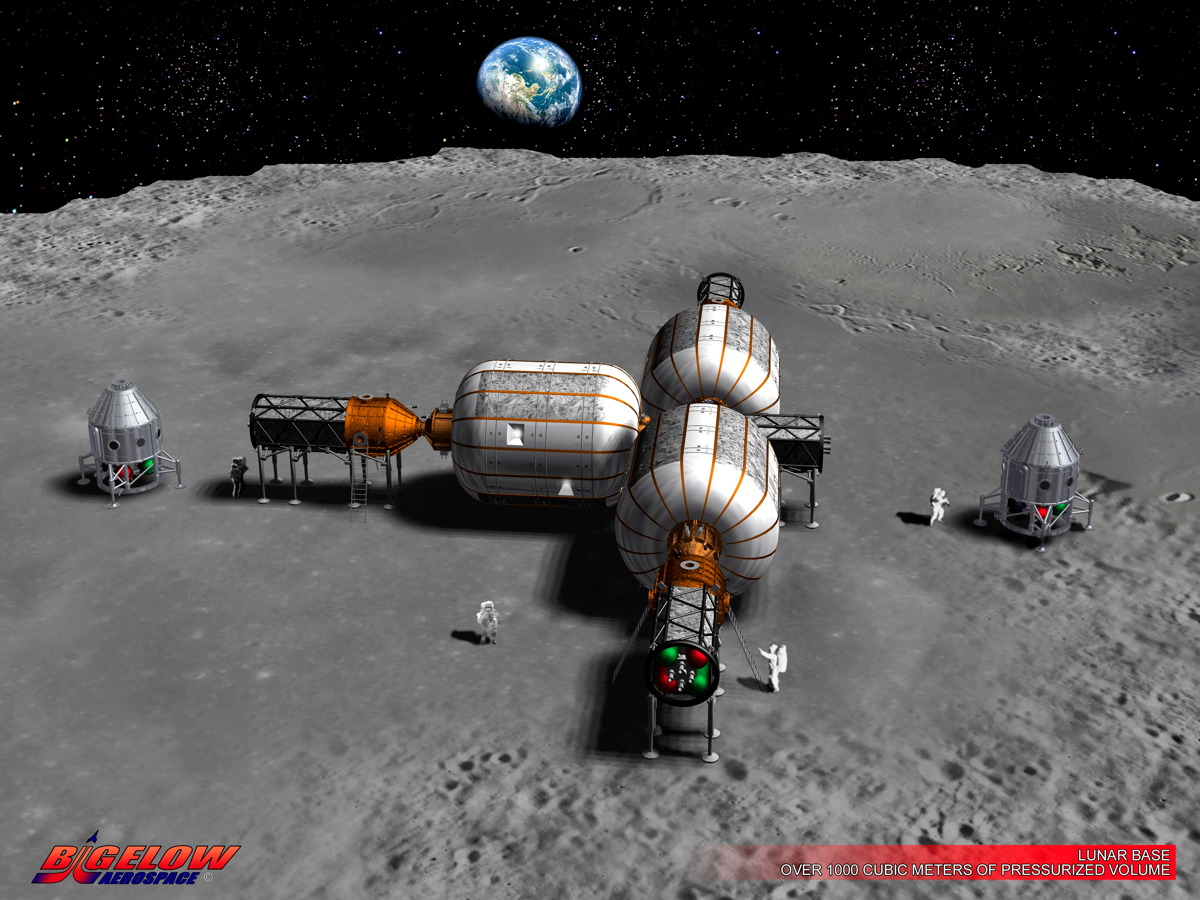

Bigelow aims to provide expandable habitats in low Earth orbit and, eventually, on the surface of the moon and Mars, for use by governments, private companies, academic institutions and other customers.

Flight-tested

BEAM won't be the first Bigelow module to reach space. The company launched its Genesis I test module to orbit in July 2006, and then lofted Genesis II a year later. Both free-flying spacecraft, which were launched from Russia, measure 14.4 feet long by 8.3 feet wide (4.4 by 2.5 meters) when inflated and offer 406 cubic feet (11.5 cubic m) of usable internal volume.

Both spacecraft have performed very well, showing that expandable modules can handle the space environment, Gold said.

"If anything, Genesis I and II were far too successful; you kind of only learn from problems," he said. "Very successful, very clean missions."

BEAM is the next step along Bigelow's path. The company won a $17.8 million NASA contract to install BEAM on the ISS; the agency intends to keep the module attached to the orbiting lab for at least two years, in the first space test of an expandable habitat in a crewed environment.

BEAM's mission is primarily a technology demonstration, and Gold said he is unaware of any specific utilization plans for the module — which, when inflated, will measure 13 feet long by 10.5 feet wide (4 by 3.2 m) and will provide 565 feet (16 cubic m) of living space — at the moment.

BEAM doesn't have any water or power hookups, so the options for use are somewhat limited. Still, Gold said the module could provide storage space, serve as a testing ground for tiny cubesats before they're deployed from the orbiting lab and host certain scientific experiments that would benefit from a level of isolation, among other potential uses.

"I also hear it'll be the quietest location on the ISS, so throw in a couple of sleeping bags, and maybe even the astronauts can stay there," Gold said.

Commercial space stations, the moon and Mars

Bigelow is dreaming much bigger than BEAM. The company is also developing a module it calls the B330, because the craft offers 330 cubic meters (11,650 cubic feet) of internal space. One 31-foot-long (9.45 m) B330 can support a crew of six astronauts, company representatives say.

Bigelow envisons the B330 — or multiple B330s joined together, as the habitats are designed with modular expansion in mind — serving as a self-contained commercial space station that could enable and support a variety of activities in orbit, from microgravity research and manufacturing to space tourism.

The timetable for the first B330 deployment is uncertain at the moment, since it's tied to the development of private astronaut taxis that can get people to orbit, Gold said.

In September 2014, NASA awarded $2.6 billion to SpaceX to finish its work on the manned Dragon capsule and $4.2 billion to Boeing for its CST-100 capsule. The agency hopes one or both of those spacecraft will be able to start ferrying astronauts to and from orbit by 2017.

"We'll be ready when they are," Gold said.

Furthermore, with a few minor variations, the B330 could also serve as the living quarters for astronauts during the long journey to Mars, as well as colonists' homes on the surface of the moon, Mars or other worlds, Gold said.

"It's a very versatile system," hesaid. "We like to think of ourselves as using the B330 in the same way that Southwest Airlines uses the [Boeing] 737 [jet] — that it's a standard module that could become the backbone in terms of future habitation."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.