Russian anti-satellite missile test was the first of its kind

The "Nudol" anti-ballistic missile system had not destroyed a target before.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Russia's latest anti-satellite test this week was unlike anything we've seen from the nation before.

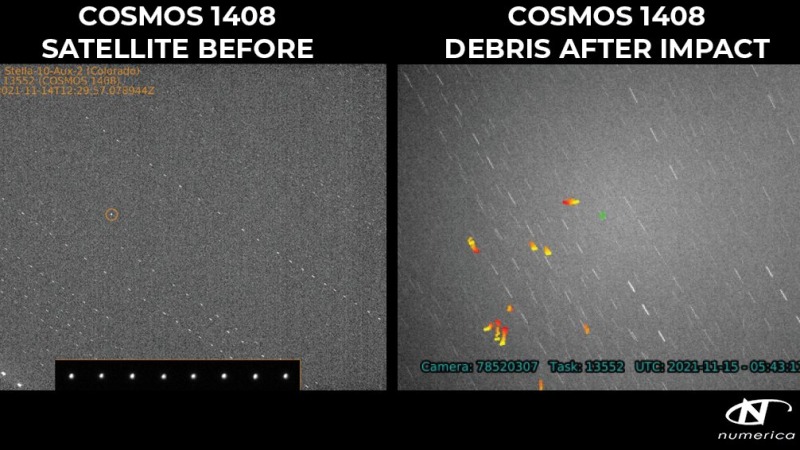

The Russian Ministry of Defense launched an anti-satellite (ASAT) missile on Monday (Nov. 15), destroying one of its own satellites and creating a cloud of space debris that is threatening astronauts at the International Space Station. While nations including Russia have conducted ASAT tests before, this test was something different.

Over the years, multiple nations including the U.S. have developed and tested ASAT technology. In 2007, China launched an ASAT missile at one of its own weather satellites, and India launched its first ASAT test in 2019. In 2020, Russia launched two ASAT missiles and separately tested another non-destructive space-based ASAT technology.

Article continues belowRelated: The worst space debris events of all time

But Monday's test was something different. This was Russia's first official intercept with its current ASAT system, known as Nudol, astrophysicist and satellite tracker Jonathan McDowell of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts told Space.com.

Different countries have different systems, but currently ASAT weapons that launch from Earth and are not space-based are relatively similar. "They're suborbital rockets that home in on a target satellite and destroy it by just sitting in the way while the satellite smashes into it at 17,000 miles an hour [27,000 kilometers per hour]," McDowell said.

Previously, with Russia, "the multiple tests we saw were all rocket tests or flight tests," space policy expert Brian Weeden, a director of program planning at Secure World Foundation, told Space.com. "This is like the 11th or 12th test of that system, but it will be the first one that was actually an intercept," meaning that the test mission actually impacted a satellite and destroyed it, Weeden said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

With earlier tests of this same ASAT system, Russia likely aimed its weapon at "an imaginary point in space, pretending there was a satellite there," McDowell said.

But this time, the test hit a real target in low Earth orbit: a defunct Soviet satellite called Cosmos 1408 that hasn't functioned since the 1980s. And, while Soviet-era ASAT tests launched from different systems, Monday's test was the first intercept with Russia's modern system, McDowell said.

Related: Don't panic about Russia's recent anti-satellite test, experts say

Russia took the unexpected step to conduct an intercept, a move that continues to place the space station's seven inhabitants (including two Russian cosmonauts) in danger and will have repercussions lasting years. But the test had other unique aspects as well.

"They took out a fairly large satellite," McDowell said, referring to the approximately 3,860-pound (1,750 kilograms) Cosmos 1408 satellite. "That's on the big end of targets that have been used."

"There's really no reason they should have used such a big target," McDowell said. "They could have used a smaller target and generated less debris." Additionally, while Russia's ASAT test occurred at a lower altitude than China's test, it happened at a much higher altitude than ASAT tests conducted by India and the United States.

"The implication of that is that the orbital debris will stay in orbit for an intermediate amount of time," McDowell said, adding that the debris from this test will likely stay in orbit for years. He estimated that the majority of the material will come down within about five years while China's test still has "a lot of debris" after 14 years and there is still material in orbit from old Soviet tests over 50 years ago.

This debris, experts expect, will continue to pose problems for satellites in orbit as well as the astronauts living on the space station.

This test was the first of its kind for Russia, but it begs the question of whether they will conduct other similar tests.

"It's a great question. How many tests do they need to do?" McDowell said. "[It] depends a little bit on whether they're seriously planning to deploy this system operationally," he said, adding that the U.S. response to the event and the political interactions between the two nations will likely play a role. But, "if they're really planning to employ an operational system, you might expect them to do it [conduct an intercept ASAT test] a number of times," he said.

Email Chelsea Gohd at cgohd@space.com or follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Chelsea “Foxanne” Gohd joined Space.com in 2018 and is now a Senior Writer, writing about everything from climate change to planetary science and human spaceflight in both articles and on-camera in videos. With a degree in Public Health and biological sciences, Chelsea has written and worked for institutions including the American Museum of Natural History, Scientific American, Discover Magazine Blog, Astronomy Magazine and Live Science. When not writing, editing or filming something space-y, Chelsea "Foxanne" Gohd is writing music and performing as Foxanne, even launching a song to space in 2021 with Inspiration4. You can follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd and @foxannemusic.