Pulsar caught binging on star before brilliant x-ray blast

You can't rush the universe.

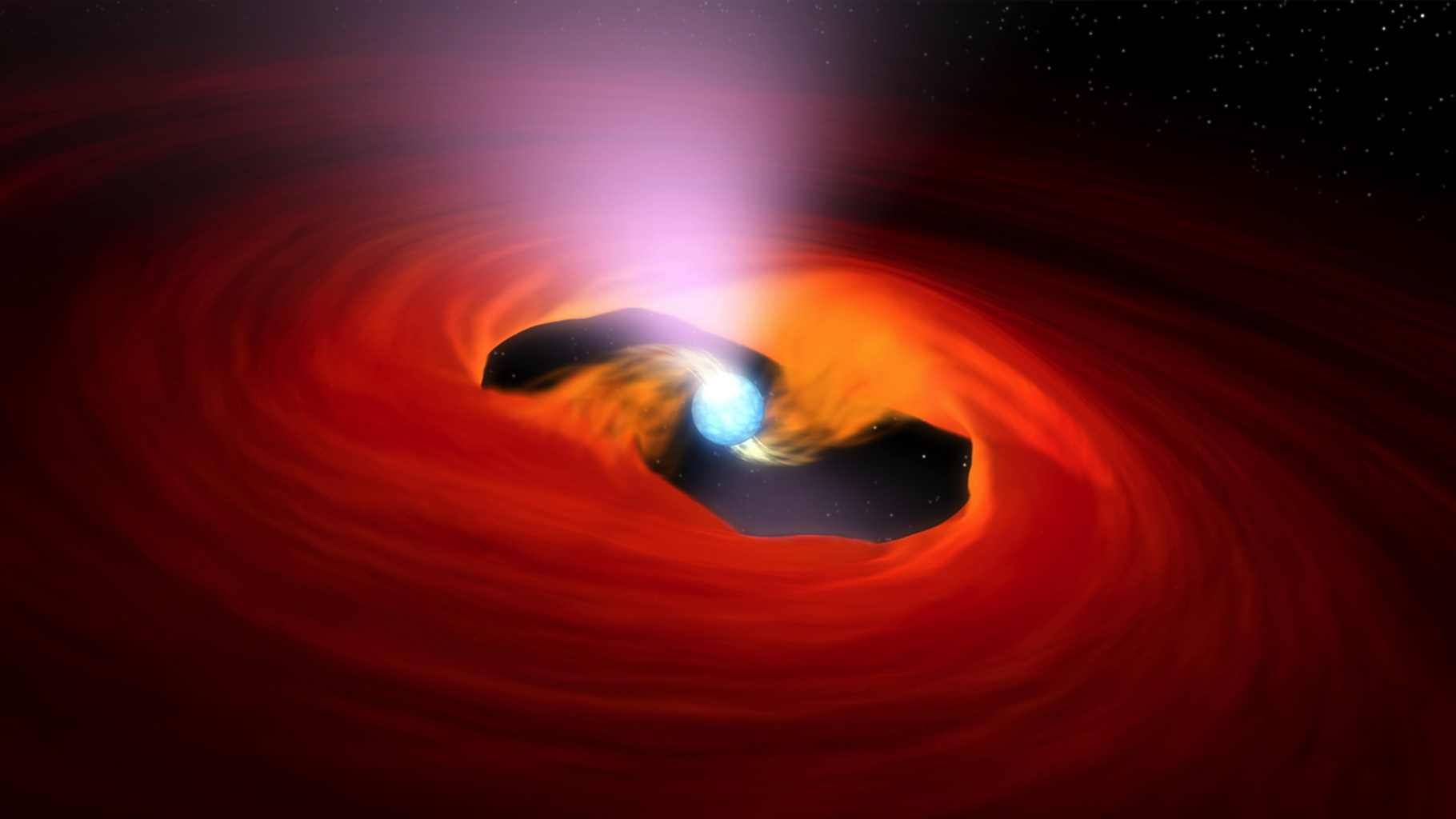

You definitely can't rush a superdense star as it gobbles up bites of a neighbor for nearly two weeks before shooting off a burst of X-rays thousands of times brighter than our sun. But thanks to some lucky timing, that process is exactly what scientists were able to watch last summer, according to new research focused on an object called SAX J1808.4−3658.

"When we first saw that optical rise, we got really excited because the underlying theory suggested and we thought that we would get the X-ray rise two to three days later," lead researcher Adelle Goodwin, a doctoral candidate in astronomy at Monash University in Australia, said during a news conference held at the virtual 236th American Astronomical Society meeting on June 1. "You can imagine how we were feeling about 10 days later, when there was still no X-ray detection and we were beginning to think that there wasn't going to be an outburst."

Related: Jocelyn Bell Burnell looks back on her incredible pulsar discovery

Goodwin had a sense of what she and her colleagues were getting into starting the research. The object they studied is a binary, or two-body system 11,000 light-years away from Earth that includes a superdense pulsar that spins 400 times per second and a tamer companion star. The pulsar, which is the rapidly spinning remnant of a star that exploded in a supernova, feeds off its companion, eventually triggering occasional bursts of X-rays.

"The pulsar will quietly pull this material from the companion star for months to years, until the disk reaches a critical size and material starts transferring directly onto the neutron star," Goodwin said, referring to the pulsar. "When this happens, this releases a massive amount of energy and is so luminous it emits high energy X-rays."

Astronomers first spotted the system in 1996, and every four years or so, scientists have noticed a massive outburst. Goodwin's team hoped that they would catch sight of just that happening during the new observations gathered last year by NASA's Swift space-based telescope. But of course, there was no guarantee.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We definitely did get lucky," Goodwin said. "It's been getting longer between the outbursts, so you never know exactly when it's going to come into outburst. By the time we put in for this monitoring proposal, the source was overdue for its outburst. So we were expecting it, but we were not even sure it was going to go off anymore."

But late in July, things started to get interesting: the object began to glow more brightly in wavelengths detectable to the human eye. Goodwin and her colleagues hustled to get a total of seven observatories focused on the object to catch the outburst in detail.

And then, they waited. Despite hypotheses that suggested the outburst should gain speed in more energetic X-rays in a few days, the object's activity stayed strictly in the optical part of the spectrum. It wasn't until 12 days later that the X-ray emissions began.

The scientists believe that delay reflects the ingredients of this particular system, which is rich in helium. Helium requires more energy to ionize and glow than the main ingredient of most such systems, hydrogen, which could explain the delayed outburst, Goodwin said. "Because this system has so much helium, we think that it needs to get to a hotter temperature, and that's why it takes longer for the rise to actually happen," she said.

In addition to the conference presentation, Goodwin said the research has been submitted to the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

- Watch NASA's X-ray-hunting pulsar detector do a cosmic dance in space

- Tour the colorful Crab Nebula with this stunning new 3D visualization

- Powerful pulsar knocks star's block off

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.