Powerful Pulsar Knocks Star's Block Off

A super-dense spinning star punched a hole right through its stellar neighbor, knocking off a giant cloud of dust and ejecting it away at nearly 15 percent the speed of light, images from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory reveal.

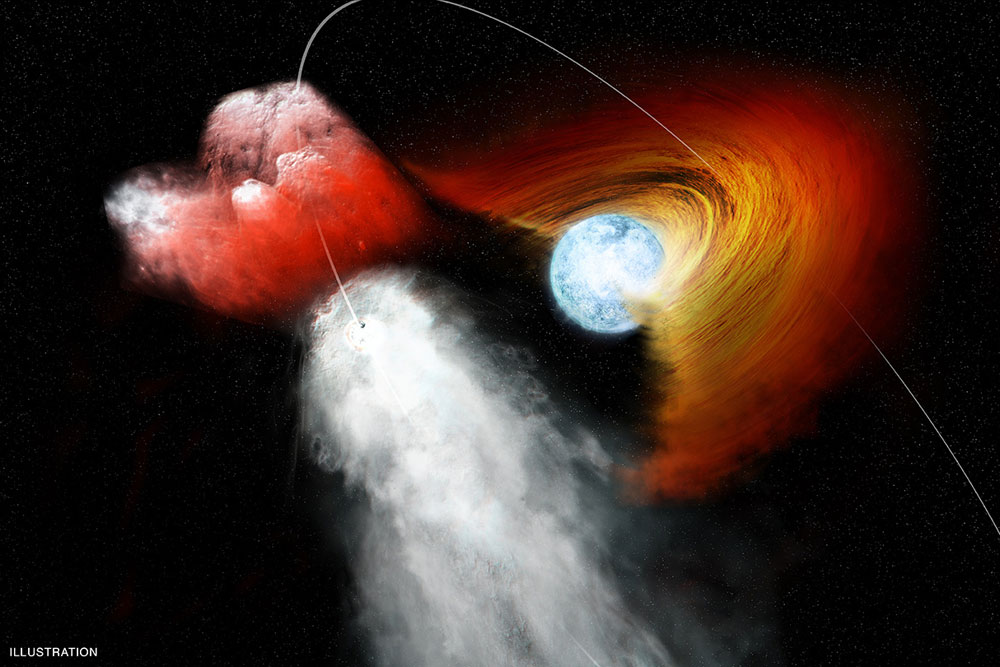

The fast-spinning neutron star, known as a pulsar, is part of a double-star system about 7,500 light-years from Earth. Its partner star is about 30 times the size of Earth's sun and also spins quickly, generating a dusty disk around itself as material flies off. Observations from the Chandra observatory show that every so often, the pulsar pierces its partner's dust disk.

"These two objects are in an unusual cosmic arrangement and have given us a chance to witness something special," study lead author George Pavlov, a researcher at Penn State University in Pennsylvania, said in a statement. "As the pulsar makes its closest approach to the star every 41 months, it passes through this disk."

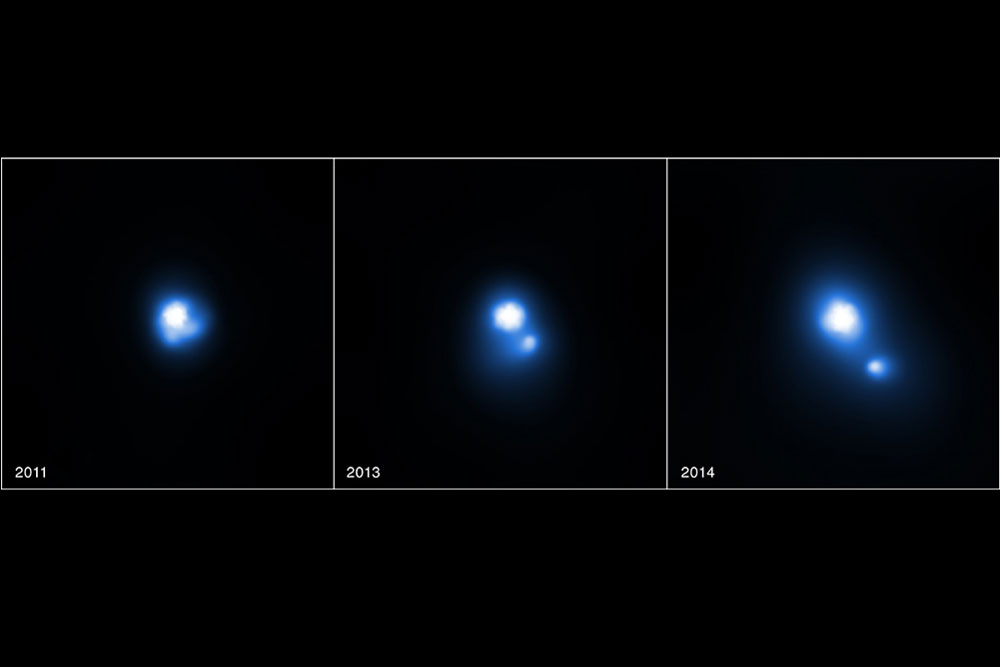

Chandra's observations of the double-star system, which scientists call PSR B1259-63/LS 2883, captured the violent interaction in X-ray light as a section of the dust disk more than 100 times our solar system's width broke free and flew off into space. [The X-Ray Universe Revealed by Chandra]

"After this clump of stellar material was knocked out, the pulsar's wind appears to have accelerated it, almost as if it had a rocket attached," study co-author Oleg Kargaltsev, an astrophysicist at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., said in the same statement.

The massive dust clump fled the star at an average of 7 percent the speed of light, but by the time the researchers looked again, a year later, it had sped up to 15 percent. The X-ray signals that Chandra picked up were probably generated from the shock waves as particles let loose by the pulsar's activity, flying at near the speed of light, hit the dust over and over and sent it blasting forward, the researchers said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And the stellar disk it came from might not be around for much longer, cosmically speaking.

"This just shows how powerful the wind blasting off a pulsar can be," co-author Jeremy Hare, also from George Washington University, said in the statement. "The pulsar's wind is so strong that it could ultimately eviscerate the entire disk around its companion star over time."

Pulsars are spinning neutron stars that can whip up an intense wind of high-energy particles as they turn, giving them a pulsing appearance. Neutron stars are stars so compact that they are only the size of a city, but so dense that the protons and electrons fuse into neutrons.

The research was detailed in the June 20 edition of the Astrophysical Journal.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.