Curious Kids: Why does it matter if Pluto is a planet or a dwarf planet?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Samantha Lawler, Assistant professor, Astronomy, University of Regina

"Why does it matter if Pluto is a planet or a dwarf planet? Because for me it just makes it more confusing in our solar system. I know that some things in space are planets and some are stars and some are other names like moons or comets. Dwarf planet is a more different name and I think it just makes it more confusing." — Timmy, 11, Kitchener, Ont.

Article continues below"Comet," "star" and "planet" are category names that immediately tell you something important about what they describe.

Our solar system consists of the sun, planets (which orbit around the sun) and small bodies (which either orbit around the sun or planets). The "small bodies" category is divided up into even smaller categories, mostly depending on the shape and size of orbits.

In 1801, astronomers discovered Ceres, which was initially categorized as a "planet." Astronomers measured that it was much smaller than the other known planets. Soon, a lot of smaller objects were discovered on orbits very close to Ceres. These small bodies were categorized as "asteroids" and we have since discovered hundreds of thousands of these in the asteroid belt.

Pluto flyby anniversary: The most amazing photos from NASA's New Horizons

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

New discoveries

A similar process of discovery and re-categorization happened for small bodies further out in the solar system.

Pluto was discovered in 1930 and was called the ninth planet in our solar system for many decades. But astronomers soon learned that Pluto was pretty different from the other eight planets: it's on a tilted orbit and it’s way, way smaller than the other planets.

Over the years, astronomers discovered more and more small, planet-like objects that crossed Pluto's orbit. These are now categorized as "Kuiper Belt objects." It was looking more and more like Pluto might fit in better with the category of Kuiper Belt objects than with planets.

In 2005, a new object was discovered in the outer solar system, Eris, that is even heavier than Pluto. This led astronomers to consider if both Eris and Pluto are planets or not. Astronomers thought this was an important enough decision that the International Astronomical Union voted on it in 2006. Astronomers decided that rather than demoting Pluto to a plain old Kuiper Belt object, they would make a new category of small body called a "dwarf planet." Pluto and Eris would both be part of this new category.

How planets form

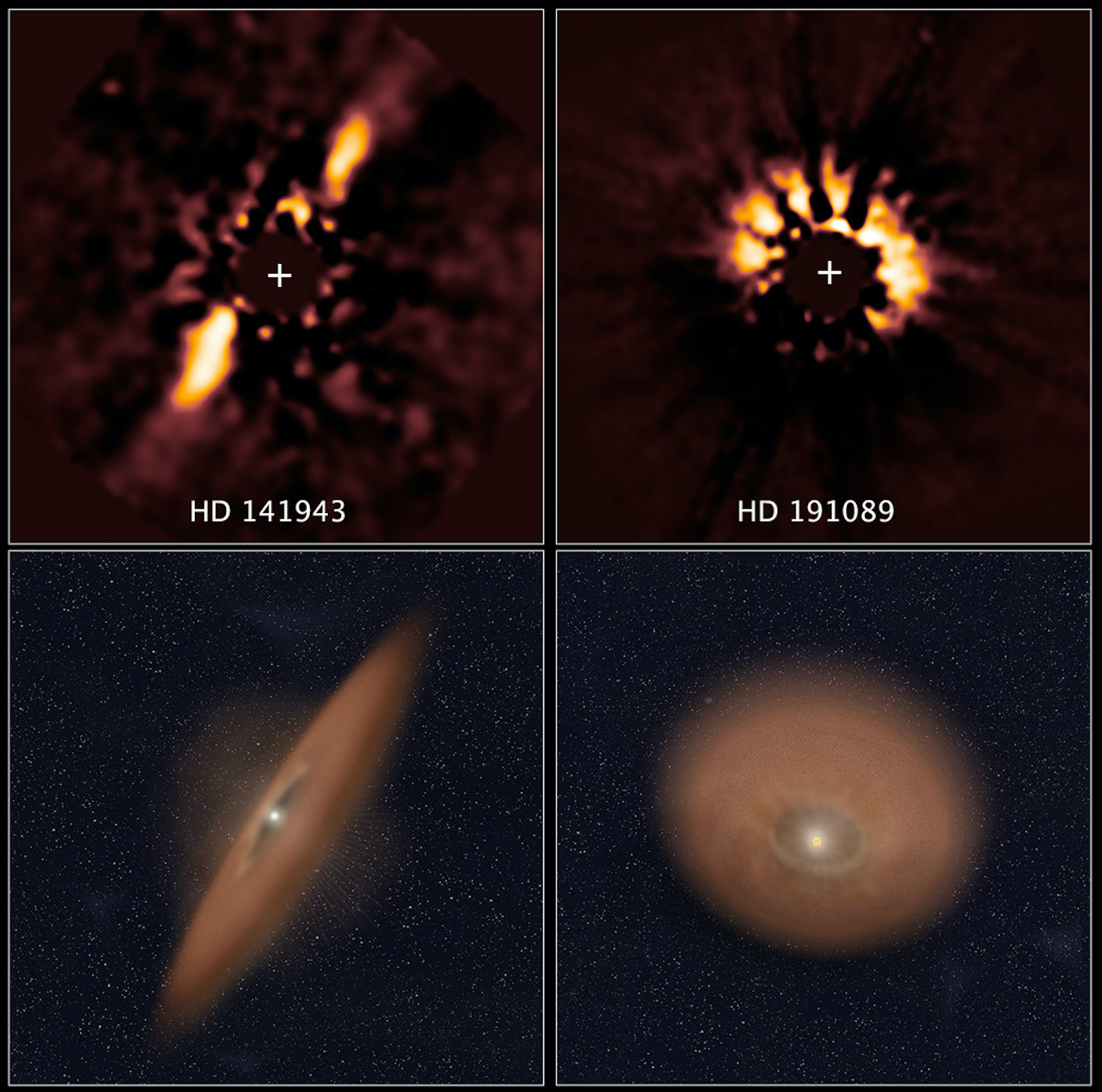

Solar systems like ours form from big clouds of dust and gas that collapse into disks around young stars, but astronomers are still learning exactly how that process works. We use telescopes to look carefully at forming solar systems far away, but they are so far that it’s really hard to see the planets forming directly.

A planetesimal — a baby planet — first forms from clumps of dust in a disk orbiting a young star. Planetesimals then grab nearby pebbles, dust and sometimes even smaller planetesimals with their gravity, which gets stronger as they get bigger. When they get to be a few hundred kilometers across, they have enough gravity to pull themselves into a round shape, which is the definition of a dwarf planet.

Measuring small bodies in our solar system, including dwarf planets, and comparing them with computer simulations is another way to see how our solar system formed. Our current theory is that there must have been a lot of dwarf planets that formed in our solar system.

Ceres, in the asteroid belt, and Pluto, Eris and about a dozen other Kuiper Belt objects are big enough to be in the dwarf planet category. This means that while they are planetesimals that grew big enough to be round, they did not develop a gravity strong enough to grab all the other planetesimals near their orbit.

Other solar systems

Astronomers have now measured more than 5,000 exoplanets, planets in other solar systems. We won't be able to measure dwarf planets there for a very long time, but the ones we've found in our own solar system can teach us about how planets form everywhere.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook and Twitter. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

I am a dynamical modeler with a strong background in observational astronomy. Lately much of my work involves "observing" imaginary planets and dust using computer code, but I still get a lot of opportunity to compare my predictions with real data from real telescopes.

I study the orbits of planets and how they evolve over time. By studying the orbits of Kuiper Belt objects and carefully taking into account observational biases, we can learn about how the giant planets migrated in the early days of the Solar System. In exoplanet systems, we can use the structure of debris disks (dusty disks around stars made by colliding asteroids) to find exoplanets that would otherwise be invisible. PhD in Astronomy from University of British Columbia, and currently an assistant professor of astronomy at the University of Regina.