Damage control for the Perseid meteor shower: 2022 dark sky opportunities

Blame it on the moon.

For Northern Hemisphere observers, August is usually regarded as "meteor month" with one of the best displays of the year reaching its peak near midmonth. That display is, of course, the annual Perseid meteor shower beloved by everyone from meteor enthusiasts to summer campers. But sky watchers beware: You will be facing a major obstacle in your attempt to observe this year's Perseid performance, namely, the moon.

Unfortunately, as luck would have it, 2022 will see the moon will turn full on August 11th and as such will seriously hamper, if not all but prevent observation of the peak of the Perseids, predicted to occur for the overnight hours of August 12-13. Bright moonlight will flood the sky all through that entire night and will certainly wreak havoc on any serious attempts to observe these meteors.

The Perseids are already around, having been active only in a very weak and scattered form since around July 25th. But a noticeable upswing in Perseid activity is expected to begin during the second week of August, leading up to their peak night. They are typically fast, bright and occasionally leave persistent trains. And every once in a while, a Perseid fireball will blaze forth, bright enough to be quite spectacular and more than capable to attract attention even in bright moonlight.

Related: August's full moon likely to outshine Perseid meteor shower this year, NASA astronomer says

Moon avoidance

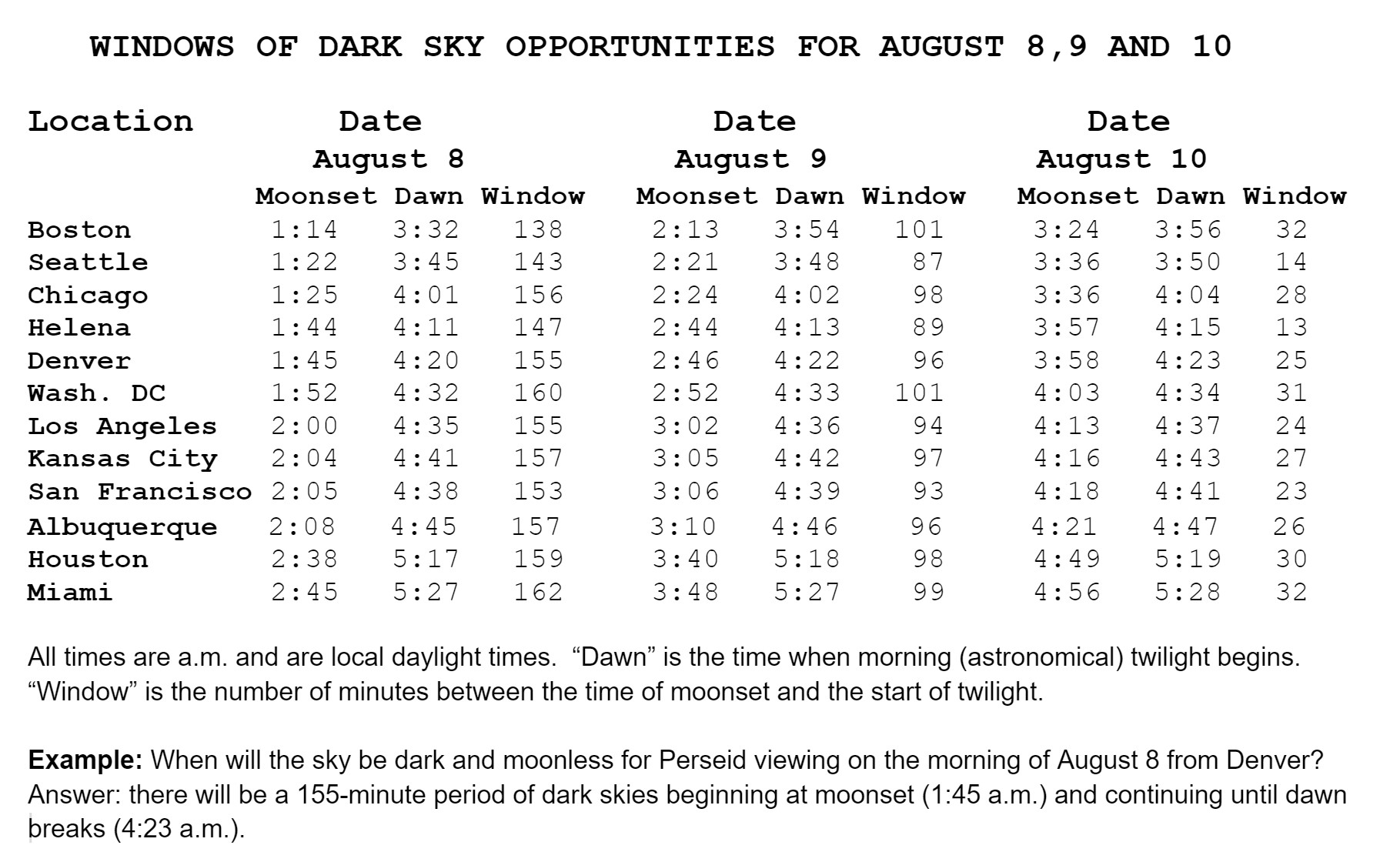

With this as a background, perhaps the best times to look this year will be during the predawn hours several mornings before the night of full moon. That's when the constellation Perseus (from where the meteors get their name) will stand high in the northeast sky. In fact, three "windows" of dark skies will be available between moonset and the first light of dawn on the mornings of August 8, 9 and 10.

Generally speaking, there will be about 154 minutes of completely dark skies available on the morning of the 8th. This shrinks to about 95 minutes on the 9th, and to only about 26 minutes by the morning of the 10th. Check the table below for examples at twelve selected cities.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Perhaps up to a dozen or so forerunners of the main Perseid display might appear to steak by within an hour's watch on these mornings.

In the absence of moonlight, a single observer might see at least 60 meteors per hour on the peak night; those blessed with exceptionally dark skies might see double this rate, but thanks to the moon, those kinds of hourly rates, sadly, cannot be hoped to be approached in 2022.

Last year: surprise!

In 2021, Perseid watchers were caught off guard by an unexpected outburst. The predicted peak of the shower came and went but by normal standards it underperformed. Spaceweather.com noted that the ". . . shower was good, but not great. When the shower peaked on Aug. 12-13, international observers counted 60 to 70 Perseids per hour—about half of the expected maximum."

But little did anyone know that the best was yet to come.

In the hours just before dawn on August 14th, about 36 hours after the predicted peak of the shower, skywatchers got a huge surprise when meteor activity spiked sharply. Canadian meteor observer Pierre Martin, observing Ottawa, Ontario, reported "multiple Perseids per minute with many bursts, sometimes 3-4 in a second." In San Diego, Robert Lunsford of the International Meteor Organization also witnessed rapid-fire streaks, 2 to 3 at a time. "It made me realize something unusual was going on," Lunsford says, "especially so far from the predicted maximum."

A repeat this year?

Peter Jenniskens, an astronomer at the SETI Institute and NASA/Ames, believes it may have been something he refers to as the "Perseid Filament," an unexpectedly dense ribbon of dust inside the broader Perseid debris zone. Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle supplies the dross that crashes into our atmosphere each summer producing the annual Perseid display. The comet loops around the sun every 133 years, shedding dust as it goes. Over time, much of Swift-Tuttle's dust is perturbed by the gravity of Jupiter, helping scatter it into the diffuse cloud that we experience every year as the Perseid meteor shower. But there is a part of the comet's orbit in a "mean motion resonance" with Jupiter where dust actually accumulates instead of dispersing. During the 1990's we interacted with the filament on multiple occasions producing unusually high numbers of meteors, but there has been little or no interaction with it during the 21st century.

Until last year.

The big question now is, can we expect the filament to return with the 2022 Perseids? The honest answer is, we simply don't know, but in spite of the unfavorable situation regarding the moon, it still would not hurt to go out before daybreak on August 14th, and check to see if anything unusual happens again. One factor that may unfortunately work against us, is the timing. Last year's outburst occurred at around 8:48 Universal Time. This year, we would be crossing the same part of our orbit where last year's meteor show took place at around 15:00 UT. That's daytime for North America and Hawaii. But skies will be dark over Japan and the western Pacific Ocean.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.