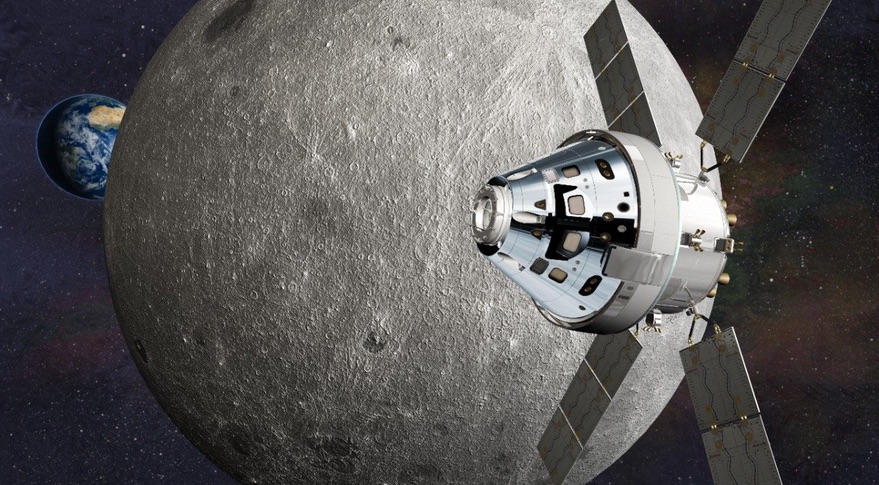

Meet the Orion Service Module, the European-built brain of NASA's new spacecraft for moon trips

The Orion's capsule European Service Module uses engines inherited from the space shuttle.

A precious cargo has arrived from Europe at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida this week: The European-built service module that, in 2023, will power the first human mission to the moon since the Apollo era.

But what exactly is the European Service Module (ESM), and why did NASA entrust the old continent's engineers with building the critical component for the historic mission?

In fact, this is already the second Orion service module developed by the European industry. The one currently mated with the crew capsule that will fly empty to the moon and back later this year or in early 2022 was also built by a consortium led by the European aerospace giant Airbus.

Assembled in Germany's northern city of Bremen, that first European Service Module (or ESM-1) is named in honor of its hometown, Catherine Koerner, NASA's Orion program manager said during an Airbus press briefing on Wednesday (Oct. 6).

Building the service module, which will handle propulsion, power and thermal control for the empty Orion capsule (and later also life-support for flights with astronauts) has been a big deal for the Europeans. The last time humans went for the moon, they were left out. Now, not only are they providing a mission-critical piece of technology but also have earned three seats for European astronauts on the planned Artemis missions.

So far, six Orion Service Modules are being built under a contract between the European Space Agency (ESA) and Airbus, and another batch of three is being negotiated. Despite the COVID 19 pandemic-related delays, Airbus managed to deliver ESM-2 on schedule and is on track to producing one service module per year, ESA said in a statement.

The ATV legacy

When designing the 14-foot (4 meters) wide, 14-foot-high cylindrical service module, Airbus engineers drew on their experience with the Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV), the autonomous expendable cargo ship that hauled supplies to the International Space Station between 2008 and 2014. The Airbus-led consortium had built five ATVs, each the size of a double-decker bus, in that period, each of which could take up to 14,330 lbs. (6,500 kilograms) of cargo to the orbital outpost. Unlike SpaceX's Dragon cargo ship, the ATVs burned upon entering the Earth's atmosphere filled with trash and unneeded items from the space station.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The ATVs, which were capable of docking on their own, were Airbus' springboard to the flagship NASA Artemis program, which promises to usher in a new era of space exploration.

"The development of the Orion Service Module started 10 years ago," Didier Radola, Orion Service Module project manager at Airbus said during the briefing. "Now we have a major solid program, which is running at full-speed. The first service module is now integrated with the Orion vehicle for the first Artemis mission. The second service module is ready for shipment to Kennedy, the third one is undergoing integration."

Space shuttle engines

Just like the ATV, the Orion service module is fitted with four 23-foot (7 m) solar wings arranged in an X-shape. Each of these wings consists of three panels that provide enough electricity to power two three-bedroom homes, according to NASA.

The service module inherited its main engine from the space shuttle. Built by Aerojet Rocketdyne, the AJ10 engine swivels from side to side to control the direction of the flight. The one on ESM-2 is a refurbished engine from space shuttle Atlantis, the fourth out of the five shuttles built by NASA and the last to fly to space. In the future, a new engine will have to be found for the Orion service module since the supply of space shuttle engines will run out with ESM-6, Airbus representatives said in the briefing.

The module also features eight R-4D-11 engines, descendants from the Apollo era, and six pods of four reaction control system engines custom-designed by Airbus that will take care of maneuvering and position control.

For its debut 25-day journey to the moon, the spacecraft will carry 8.6 tons of fuel, enough to demonstrate its capabilities by flying more than 40,000 miles (64,000 kilometers) beyond Earth's natural satellite, Airbus said in a statement.

A lot of moving parts

The 13-ton service module consists of more than 20,000 components including the engines, electrical equipment, solar panels, fuel tanks and life support parts. All that is bound together with several kilometers of cables and tubing.

After completing its trans-Atlantic voyage, ESM-2 will be mated with the Orion Crew Module and undergo two years of testing before the ground-breaking crewed launch of the Artemis 2 mission, which is currently scheduled for September 2023.

During the crewed mission, the service module will carry water and oxygen and manage the technology maintaining breathable atmosphere and comfortable temperature for the four pioneering astronauts.

Future Orion spacecraft will dock with the new space station to be built in the orbit around the moon, the Lunar Gateway.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.