NASA's Gateway moon-orbiting space station explained in pictures

1) Introduction

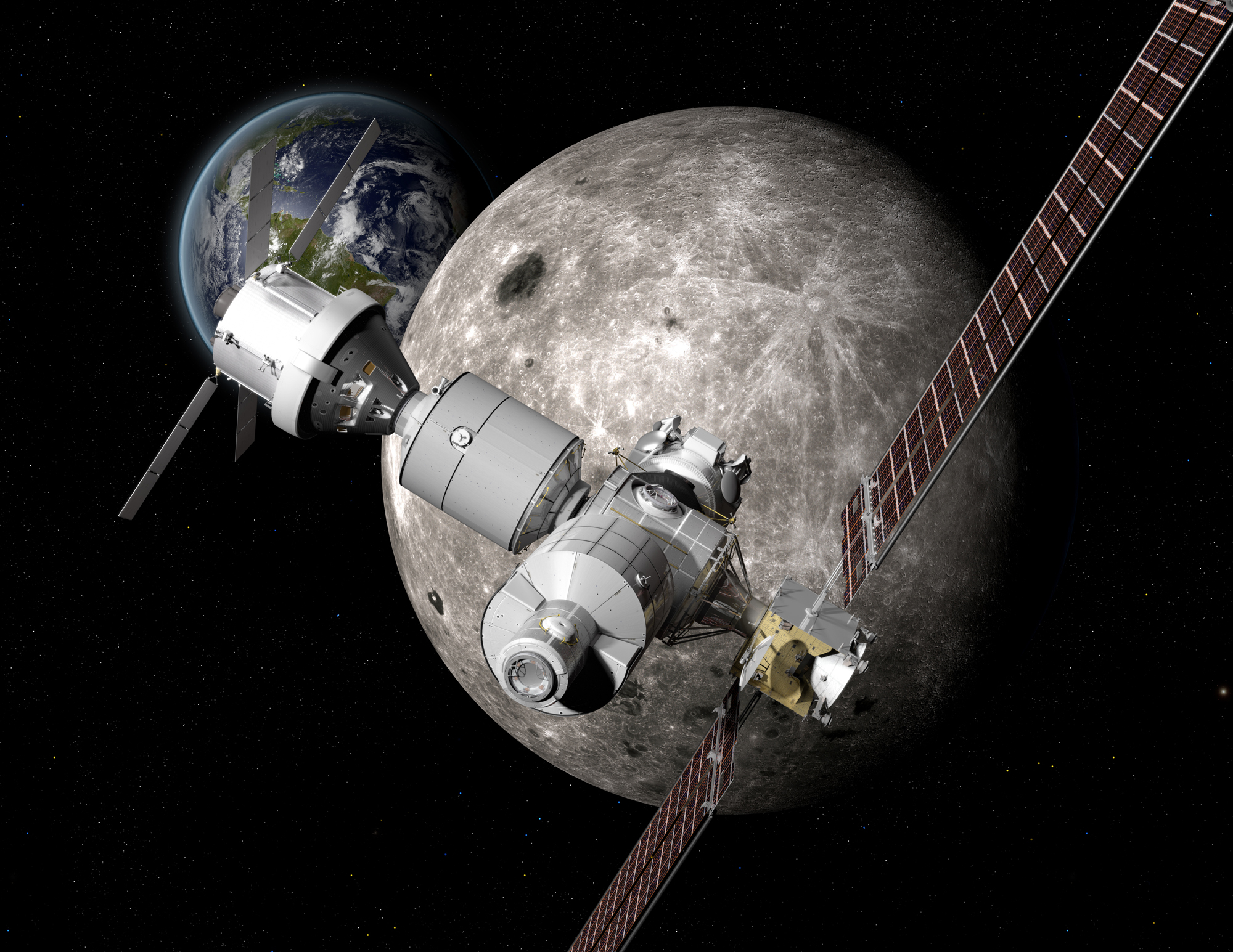

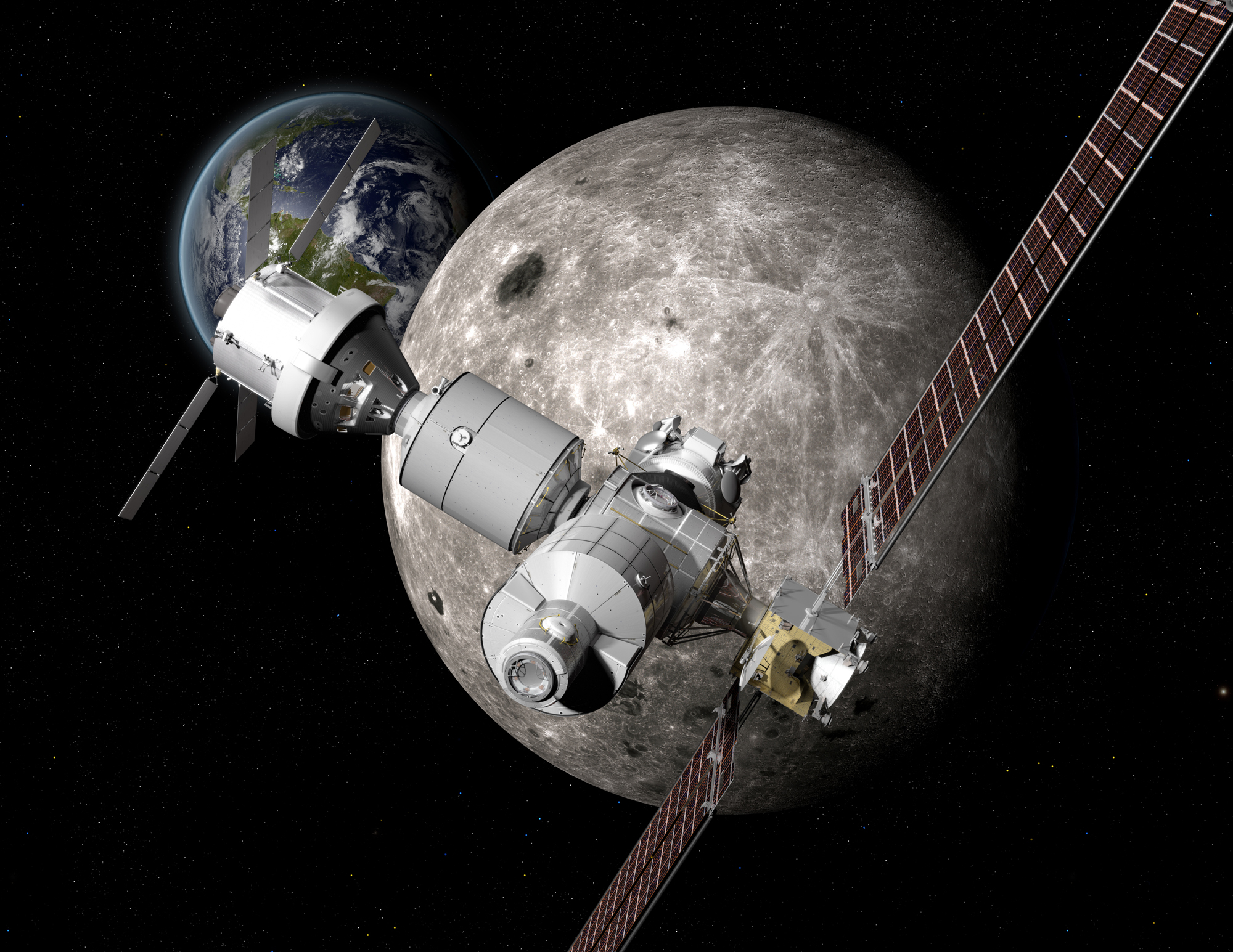

NASA's next crewed space station will be near the moon. The planned lunar Gateway space station will house crews for between one and three months so they can perform a series of ambitious jobs: to conduct science experiments further away from Earth for long periods of time; to support missions on the surface; and perhaps to even do far-out engineering work such as telerobotics.

This gallery details some of the main history and components of Gateway, as well as what it may be used for in the future. For now, NASA plans to bring astronauts to Gateway sometime in the 2020s, possibly in support of the Artemis moon-landing program. Artemis was targeting a 2024 moon landing, although an August 2021 report from the Office of the Inspector General said this target is "not feasible" due to spacesuit development delays. More timeline changes may therefore be in store.

Related: NASA's grand plan for a lunar Gateway is to start small

2) Gateway history

NASA has wanted a lunar space station for decades, and the Gateway concept dates back at least to the early 2010s. In 2012, NASA publicly discussed the idea of a lunar station on the moon's far side — then called the Deep Space Habitat. Around 2014 and 2015, NASA began to publicly discuss "cislunar habitats" to fly humans on longer missions in the 2020s.

Gateway's name has also changed a few times. NASA documentation in 2017 refers to a Deep Space Gateway space station around the moon. In 2018, the space station was renamed the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway (LOP-G) in NASA's proposed 2019 budget. These days, the agency prefers using the simpler term "Gateway."

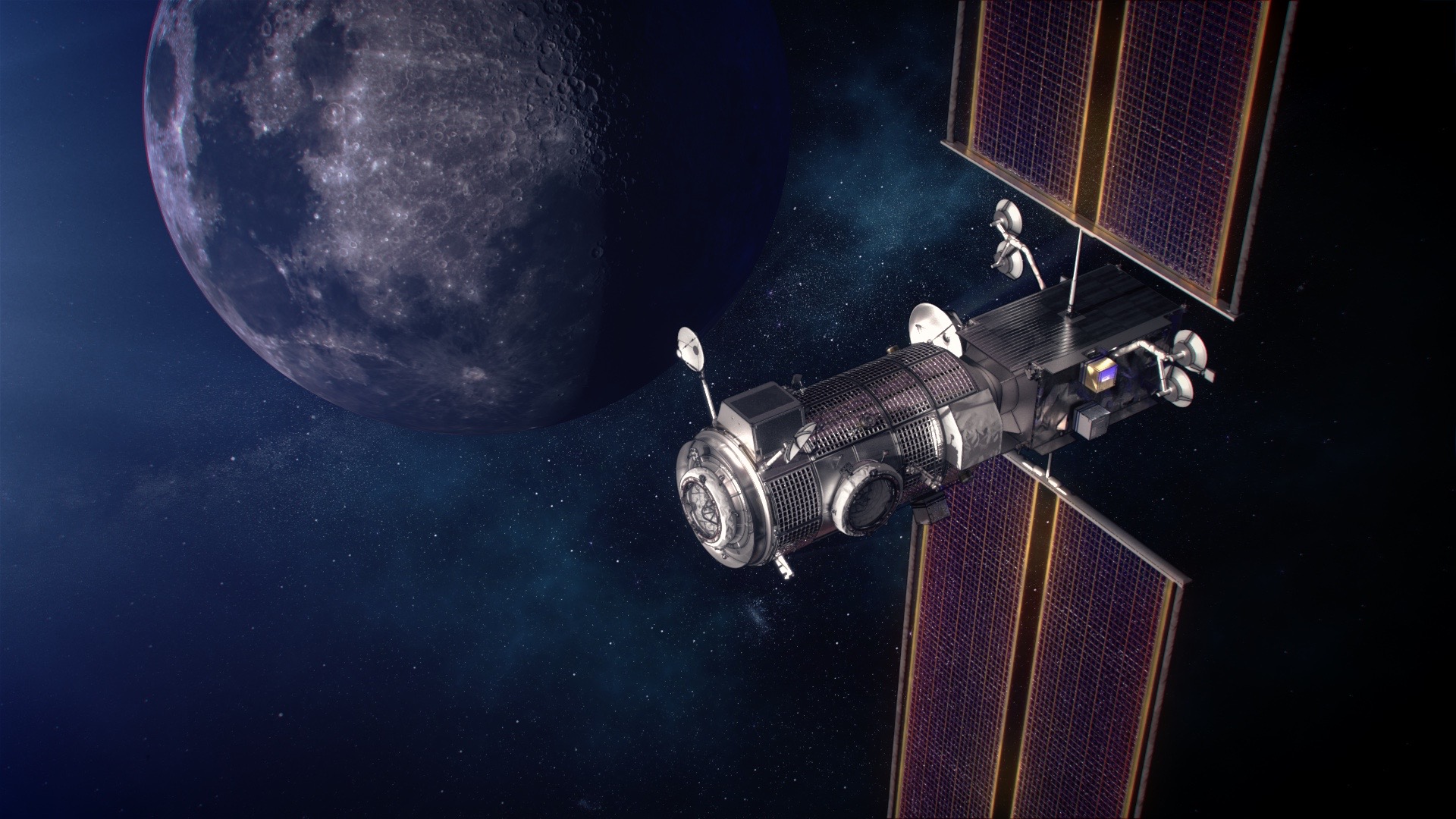

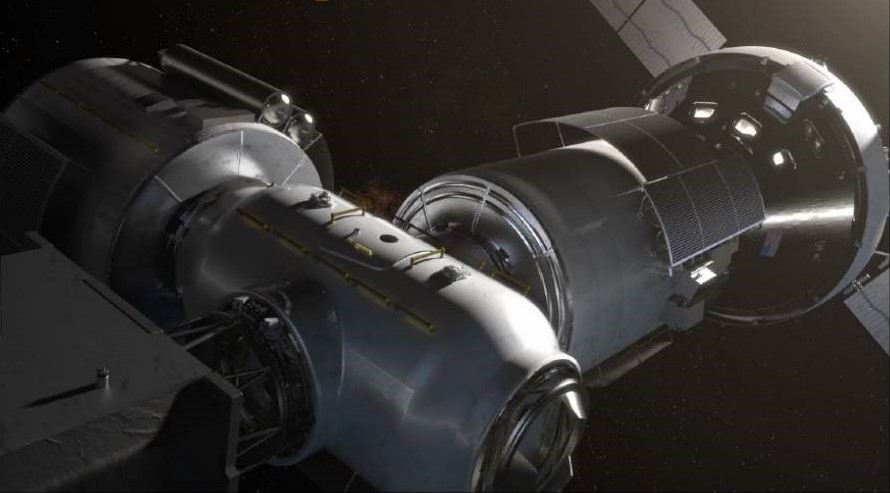

3) Habitation and logistics outpost (Northrop Grumman)

In 2019, NASA tapped Northrop Grumman to build the habitation and logistics outpost (HALO). The design of the habitation module is based on the Cygnus cargo spacecraft, which regularly ferries equipment and supplies to the International Space Station (ISS). NASA also made its selection of Northrop Grumman because the company made progress on modifying Cygnus for a habitation module, and Cygnus is small enough to be launched on existing commercial launch vehicles (simplifying the development of Gateway).

The habitat, Northrop Grumman said, "can sustain up to four astronauts for up to 30 days as they embark on, and return from, expeditions to the lunar surface." Northrop Grumman received a further $187 million to design the habitat module in June 2020 to prepare for its preliminary design review, which was completed that November. The company then received a $935 million contract from NASA in July 2021 to complete the design and development of HALO. The module is scheduled to launch to the moon's vicinity in 2024 aboard a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket.

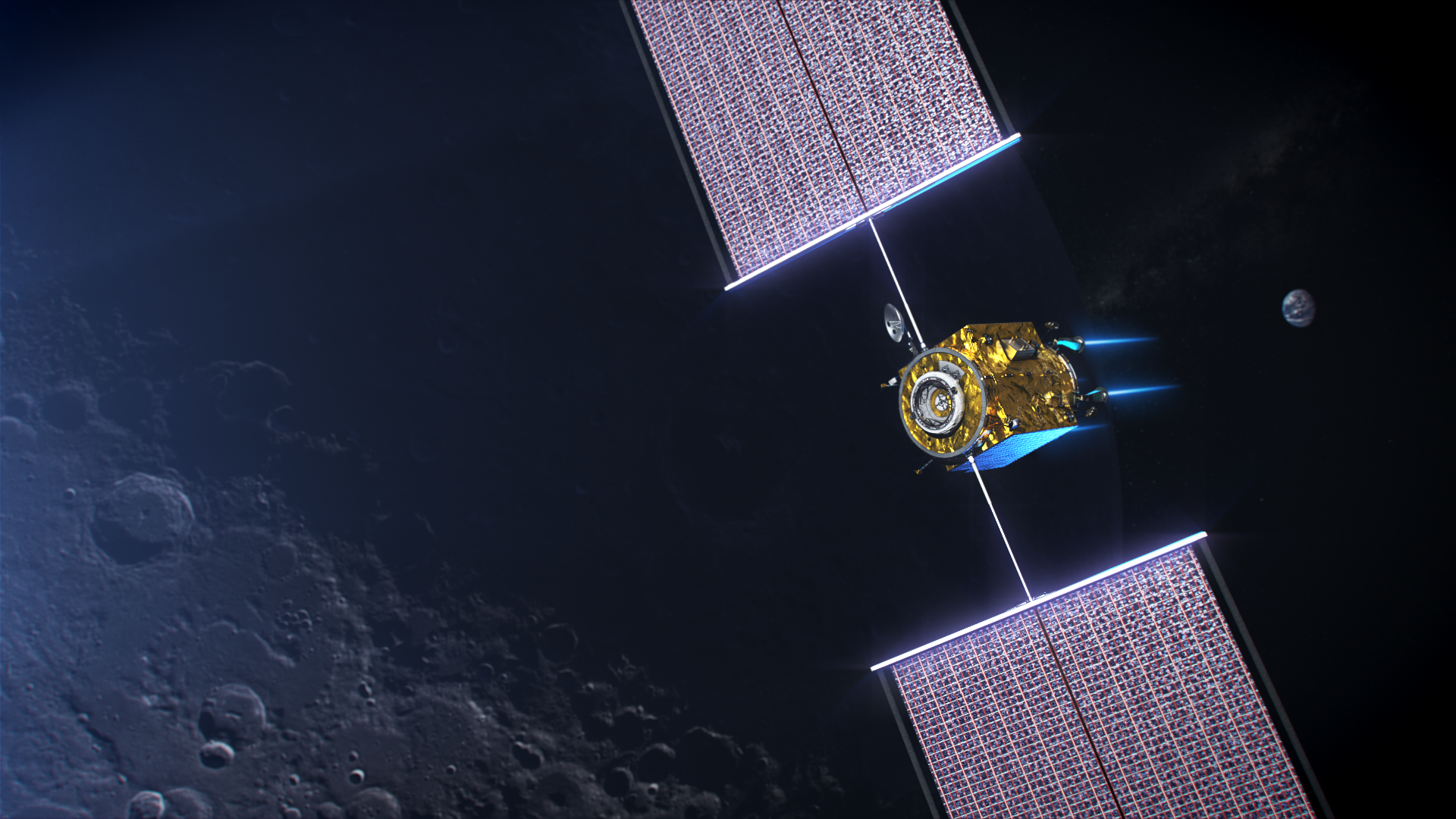

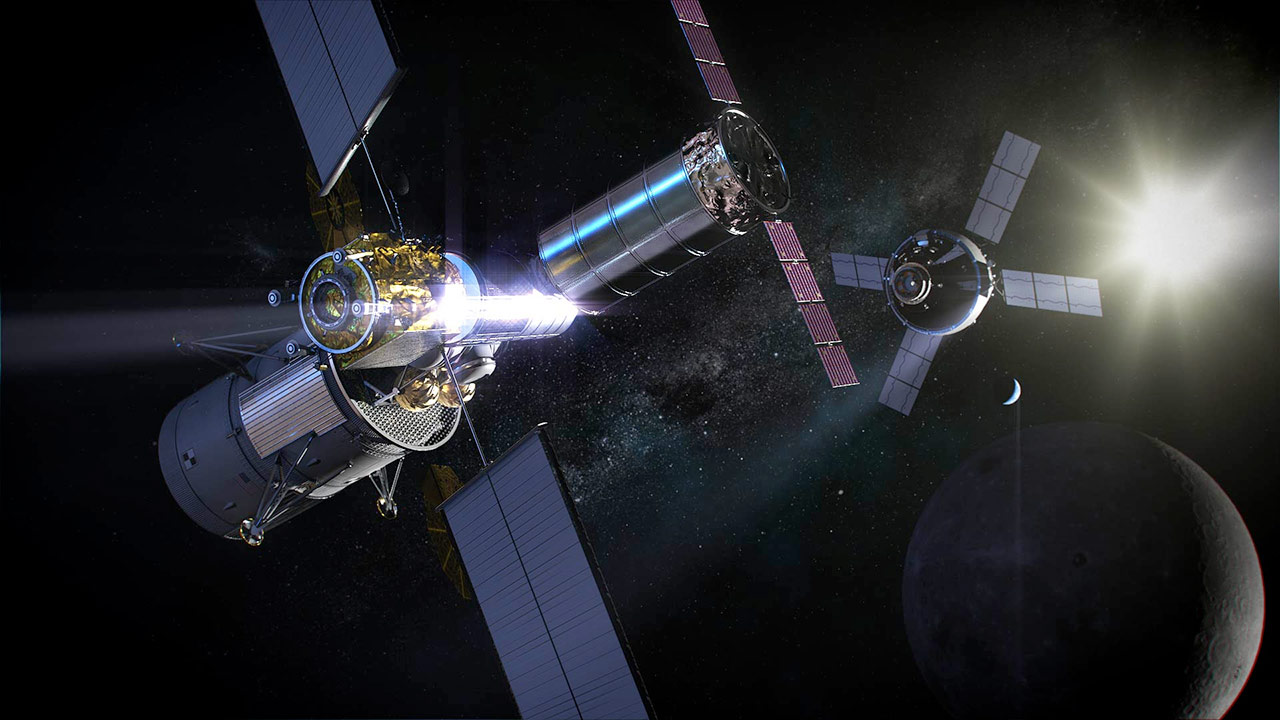

4) Power and propulsion module (Maxar Technologies)

The power and propulsion module of Gateway will be based on a salvaged design from propulsion studies related to NASA's Asteroid Redirect Mission, which was canceled in 2017. In May 2019, NASA selected Maxar to build the power and propulsion element of the Gateway. The element will be a solar electric propulsion unit that can be maneuvered around the moon and adapted for a Mars journey as well, according to NASA. Maxar is best known in space tech for a large fleet of Earth-imaging satellites.

Maxar completed a system requirements review for the module in 2019, and passed two other key reviews in early 2021. Along with HALO, the power and propulsion module is expected to launch toward the moon aboard a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket in 2024.

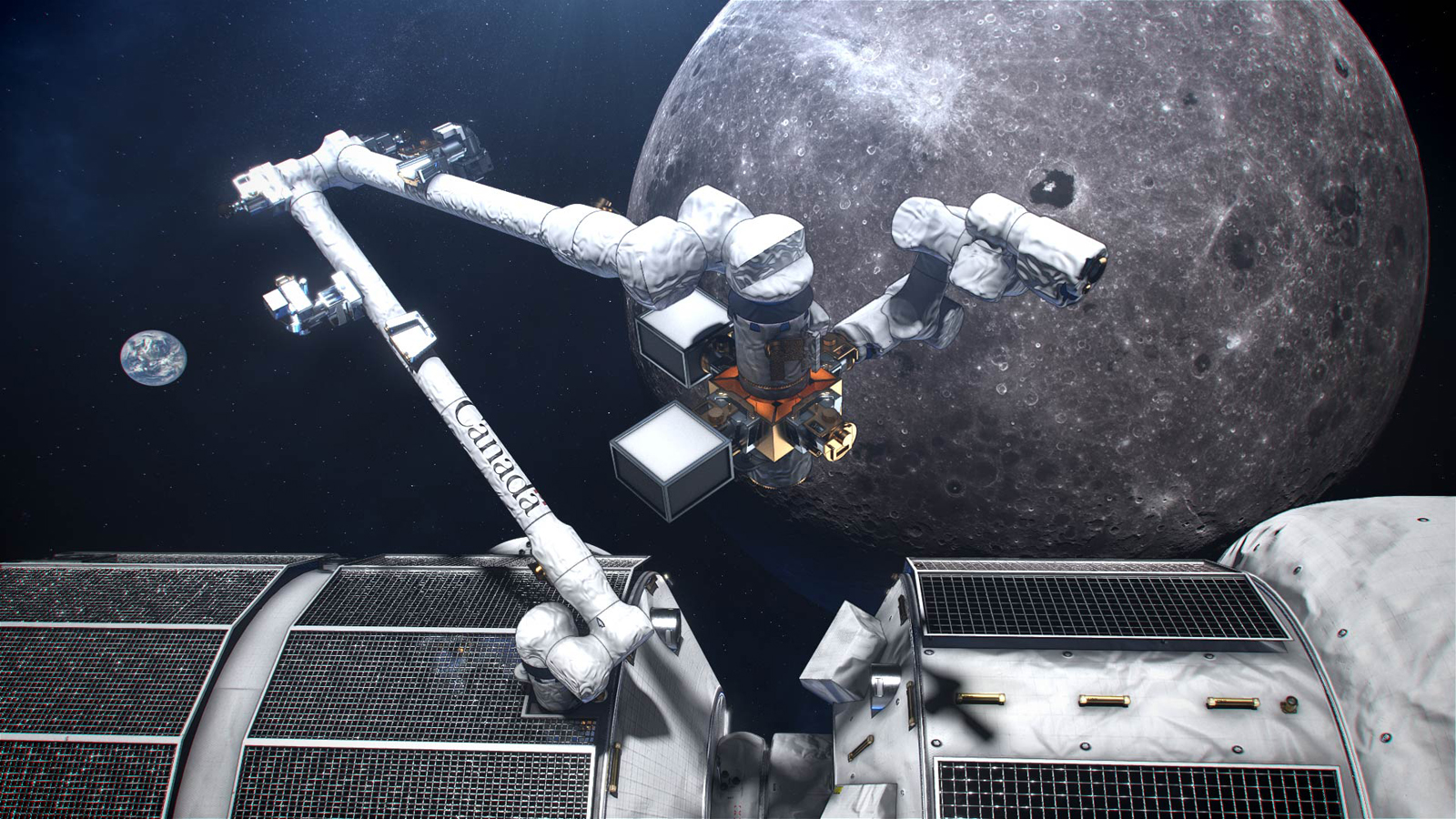

5) Canadarm3 (MDA)

The Canadian Space Agency announced in May 2019 that it would supply a next-generation robotic arm to Gateway called Canadarm3, building on previous generations of robotic arms supplied to the space shuttle and ISS programs. Canadarm3 is designed to be built with a measure of machine learning so that the arm can do maintenance and surveillance on Gateway in between astronaut missions, as the lunar space station won't be continuously occupied. In exchange, NASA pledged in 2020 to fly a Canadian astronaut on Artemis' first moon-orbiting mission — continuing a long-standing tradition of rewarding Canadian space robotics contributions with astronaut seats and orbital science time.

Canada pledged to spend $2.05 billion Canadian dollars ($1.56 billion USD at the time) on Canadarm3 and a Lunar Exploration Accelerator Program (LEAP) over 24 years. LEAP is a Canadian program meant to encourage businesses to research lunar missions with applications in robotics, health and artificial intelligence. The Canadian company MDA (which also managed Canadarm and Canadarm2) received a series of Canadarm3-related contracts, most recently $35.3 million in July 2021 for the preliminary and detailed design of external robotics interfaces that will enable Canadarm3 to operate.

6) Cargo ships (SpaceX)

In August 2019, NASA issued a request for proposals from American companies to create spacecraft that could carry and deliver pressurized and unpressurized cargo to Gateway. Similarly to ISS cargo ships, the craft would launch on a commercial rocket and remain docked at Gateway for up to six months before being removed for autonomous disposal.

And in March 2020, SpaceX was announced as the provider of Gateway's cargo services, using a future version of its cargo spacecraft, Dragon. Dragon is already one of the main supply ships for the ISS. The newer ship, called Dragon XL, will carry more than 5.5 tons (5 metric tons) of cargo to Gateway, SpaceX representatives said via Twitter. Other companies may be selected to join SpaceX for resupply services, NASA said at the time, with the total value of all deals capped at $7 billion.

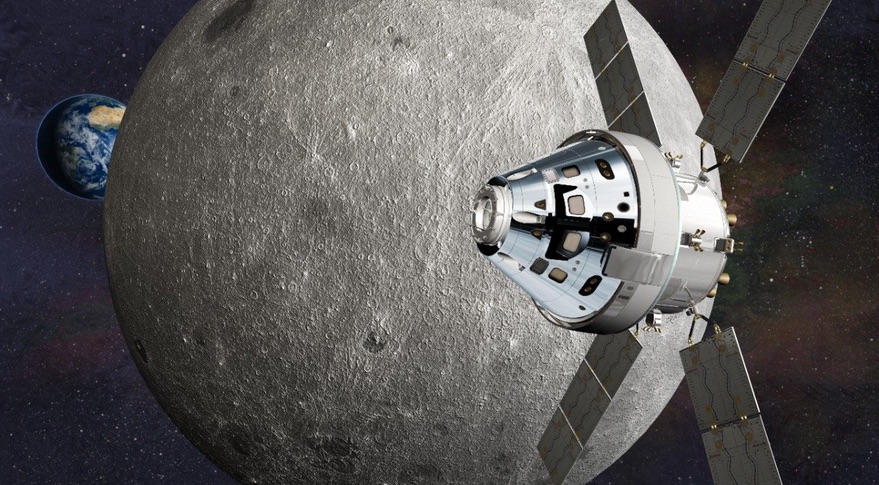

7) Crew ships (Lockheed Martin)

The first Gateway missions will likely be performed by Lockheed Martin's Orion spacecraft, although other crewed vessels may venture to the space station in later years. The Orion spacecraft's development history long predates Artemis: It has outlived several since-canceled NASA initiatives, including the administration's Constellation program to bring humans to the moon and Mars, and a flexible-destination approach NASA adopted for almost a decade after the 2010 cancelation of Constellation.

Orion has successfully performed one test flight to date — a high Earth-orbiting mission called Exploration Flight Test-1 (EFT-1) — on Dec. 5, 2014. Orion's next flight, Artemis 1, is expected in late 2021,but it has been delayed several times since 2017 due to issues with the Space Launch System rocket. The spacecraft will include a crew module and service module, with vital spacecraft systems for power, fuel and oxygen generation — similar to the Apollo command module that orbited the moon in the 1960s and 1970s.

8) Strange 'halo' orbit

Gateway will operate in a new orbit that’s not yet used by lunar spacecraft, either crewed or uncrewed. The pathway is called a "near rectilinear halo orbit" (NRHO), which enables the spacecraft to swoop low over the south pole while flying high at other points in its orbit.

NRHO will range between 1,860 miles and 43,500 miles (3,000 and 70,000 kilometers) from the surface of the moon, according to the European Space Agency, and will rotate together with the moon. The orbit will take roughly seven days to complete and will pass through a minimum of eclipses, allowing the sun to keep Gateway powered for much of the time. The multi-partner CAPSTONE Cubesat mission will test out the orbit after launching no earlier than October 2021.

9) Non-continuous crew occupation

Unlike the ISS, which has been continuously occupied since 2000, Gateway will not see crews constantly trading duties in a series of unbroken rotations. Instead, the crews will only remain on the space station for about 30 to 90 days at a time, and will leave Gateway uncrewed in between.

This situation is largely because flying NASA astronauts to lunar orbit is very expensive compared to low Earth orbit, requiring combinations of Space Launch System rockets and Orion spacecraft. This will likely leave Gateway uninhabited for most of its lifetime, unless other providers choose to send crews out to the outpost in between to fill in the gap, as Interoperability standards will allow international companies and crews to dock with and use the space station.

10) Waystation for lunar landings or telerobotics

One of Gateway's main functions could be acting as a waystation for spacecraft and crew on their way to and from lunar landings. NASA's vision is to have an Artemis Base Camp in Shackleton Crater, a region of the moon that appears rich in water ice, based on uncrewed spacecraft data. The facility will eventually require supplies for water, waste disposal, landing vehicles, communications and radiation shielding, NASA said. The facility is also anticipated to include astronaut mobility systems and a far-side radio telescope, along with a host of experiments.

Lunar telerobotics may also be possible from Gateway. Astronauts could operate a series of rovers or movable craft that examine craters or construct radio antennae for telescopic observations. That said, it remains to be seen whether such activities are a good use of astronauts' valuable — or if it’s better to do these activities from Earth, where there would be a two-second time delay between issuing a command and it being received on the moon's near-side surface.

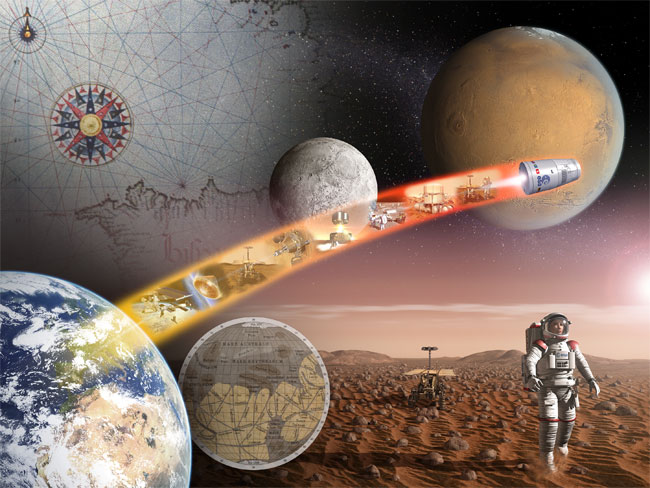

11) Waystation for Mars?

Gateway's design is still evolving, and it is hard to make predictions about how it will support lunar exploration, let alone Mars exploration. In 2020, for example, media reports indicated that Gateway would be removed from the "critical path" to Artemis exploration. However, NASA maintains that many of the "lessons learned" from Artemis and Gateway will be useful for eventual Mars exploration, ranging from how to supply astronauts from far away, to keeping crew members safe, to learning to "live off the land" on another world via in-situ resource utilization.

While Mars connections remain speculative and subject to change, past proposals for Gateway with regard to the Red Planet include using it as a waystation for samples, building up international partnerships with an eye to preparing for Mars, and using Gateway as a "Mars analog" to prepare for Red Planet missions.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.