NASA Shapes Science Plan for Deep-Space Outpost Near the Moon

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

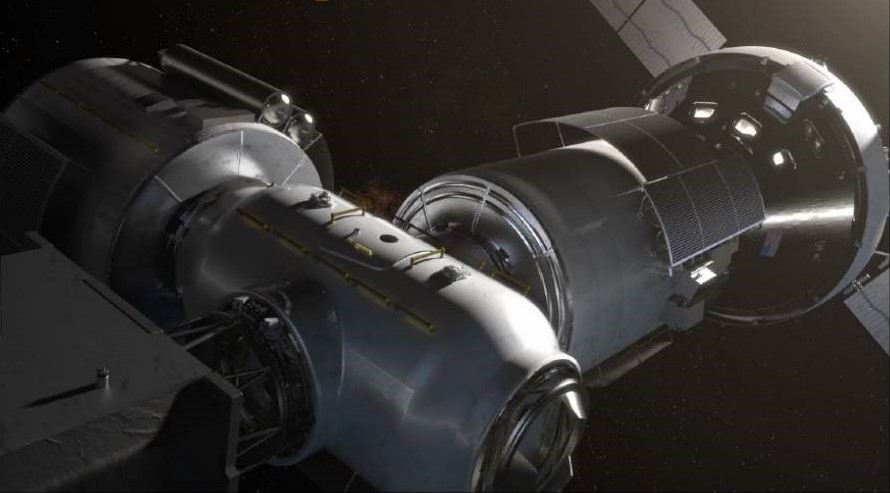

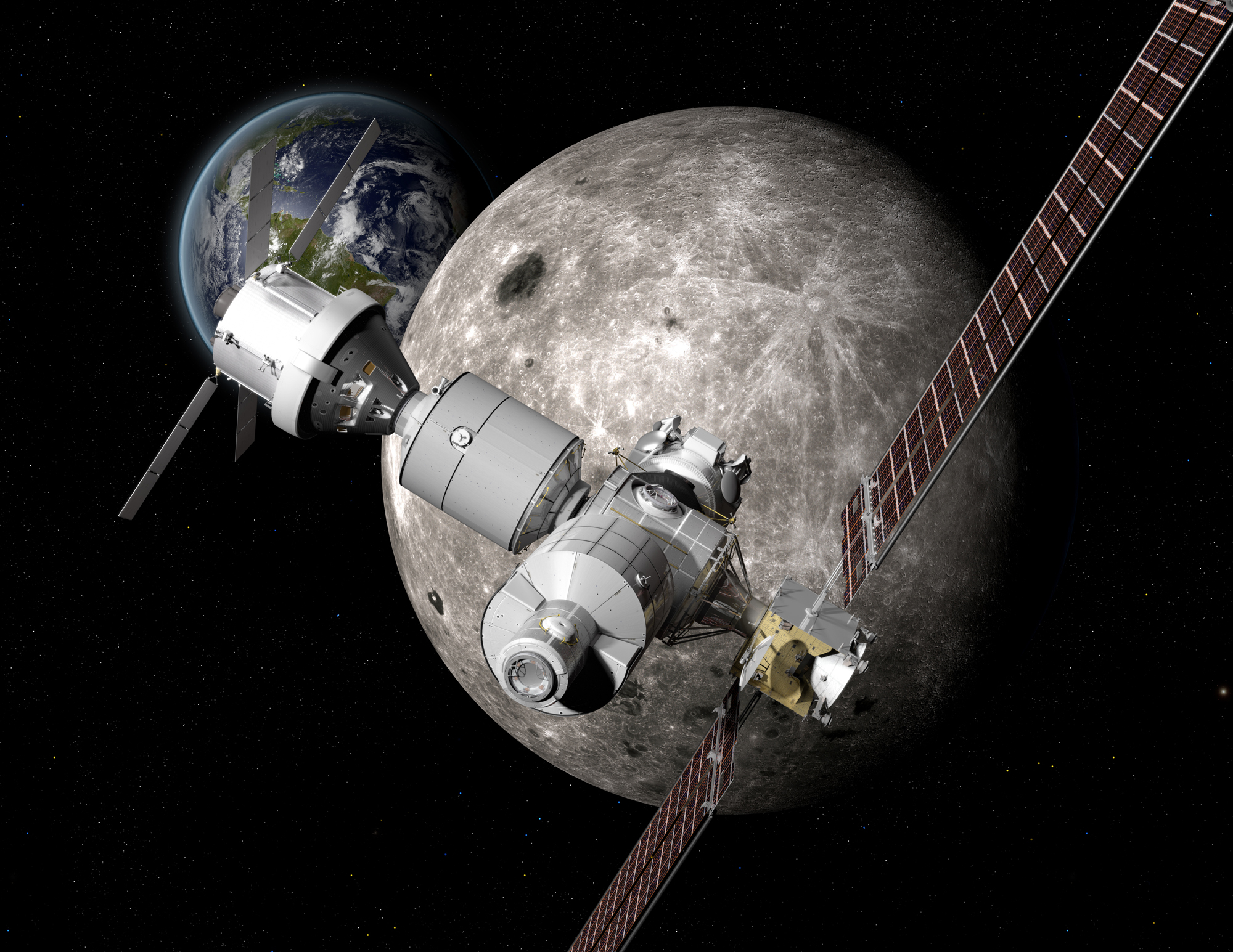

DENVER — NASA is pressing forward on plans to build a Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway, an outpost for astronauts positioned in the space near Earth's moon.

According to NASA, the Gateway will not only be a place to live, learn and work around the moon but will also support an array of missions to the lunar surface. And scientists foresee a host of uses for the station.

By making use of a suite of instruments housed on or inside the structure itself, or free-flying nearby, scientists could make Earth and solar observations.They could also carry out astrophysics and fundamental physics experiments as well as human physiology and space biology studies.

NASA's fiscal year 2019 budget request calls for launching the first element of the Gateway – its power and propulsion module – into space in 2022. NASA plans to launch the module through a competitive commercial launch contract in an effort to both speed up establishment of the Gateway and advance commercial partnerships in deep space. Under that plan, construction of the Gateway would be complete after two additional launches by 2025, rounding out the complex with habitation, logistics and airlock capabilities. [6 Private Deep-Space Habitat Concepts for Mars]

Breadth of science

Several hundred scientists gathered here between Feb. 27 and March 1 to take part in a Deep Space Gateway Concept Science Workshop that discussed how best to use what is billed by NASA as developing "a strategic presence" in cislunar space (or the space near the moon).

"We invited scientists from a wide range of disciplines and thrilled with the breadth of science that's represented," said Ben Bussey, chief exploration scientist in NASA's Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate.

"The different science areas are really embracing the idea of a human-tended Gateway around the moon and it doesn't compete with what they currently do. It represents a new opportunity for them," Bussey told Space.com. Even though the Gateway isn't science-driven, he said, NASA would like science to be performed at the facility and wants to identify what the Gateway could enable.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

One thing is clear: Don't think of the Gateway as International Space Station 2.0.

"It's a lot smaller," Bussey said, and would be an uncrewed platform that has a crew once a year.

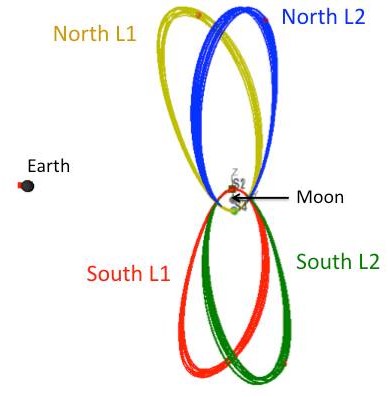

The Gateway could be parked in what scientists call a Near Rectilinear Halo Orbit (NRHO), an orbit in cislunar space that could serve as a staging area for future missions.

Such orbits, which make close passes by the moon and loop far out, have the advantage of being near the moon, but always keep a station within the line of sight of flight controllers on Earth, as well as in sunlight for solar arrays.

"It ends up being a very interesting orbit," Bussey said, with NRHOs now seen as a viable candidate for long-term cislunar operations and aggregation.

Multiple priority goals

"A Gateway in the vicinity of the moon has been the goal of scientists and designers of space exploration scenarios for almost two decades," said Harley Thronson, a senior technologist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

More than a half century later, Thronson said, professionals at the Deep Space Gateway workshop discussed how a habitation system might be adapted to achieve multiple priority goals in space and Earth sciences. "The Gateway, as planned, offers some of the same advantages to scientists as the space shuttle and the International Space Station , although in a much different location," he said.

Learning from the experience of NASA's space shuttle missions' servicing of the Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers at the workshop presented concepts for upgrading future very large observatories "or even one day actually assembling them in space, taking advantage of both astronauts and robots on site," Thronson said.

Whole-Earth observations

The Gateway's unique vantage point permits astronaut operation of telerobots on the lunar surface, Thronson said.

These could include exploring the youngest craters on the moon, or laying out radio antennae to investigate the faint radio emission from hydrogen, emitted when the universe was a tiny fraction of its present age, he said. No other planned observatory will observe the universe any younger, he added.

"The Earth itself could become a target of observation from the Gateway," Thronson said. "Remarkably, there have been very few whole-Earth observations from space that closely duplicate how Earth-like planets might appear to future astronomical observatories. A telescope at the Deep Space Gateway might accomplish this."

Lunar telerobotics

The role of exploration telepresence from the Gateway also garnered discussion at the meeting.

"But we really don't have a lot of information about the value of doing lunar telerobotics from the Deep Space Gateway, as opposed to doing it from the Earth," said Dan Lester, a senior research scientist at Exinetics in Austin, Texas.

Lester said that telepresence depends a lot on the cognitive load of what you're trying to do, and the price of modest control latency. "If you're trying to pick up a rock … probably not that much. If you're trying to tie a shoelace, it would make a big difference," he said.

Some would say that telerobotic control from the Gateway, or from an Orion spacecraft, enables operation on the moon's far side, Lester added. On the other hand, it is cheap and easy to put a relay satellite at, for example, the Earth-moon Lagrangian point (L2) that would provide direct communications from Earth to the lunar far side.

"[There's] no question, however, that the value of low latency telepresence for Mars is enormous, and implementation of that control strategy on the moon is exquisite practice for doing it on Mars in the future," Lester said.

Agency alignment

Just like the International Space Station today, where 15 different countries work together in space, there will be a role for international cooperation on the NASA's Lunar Orbiting Platform-Gateway.

"The NASA Gateway Science workshop was a valuable meeting that highlighted the many opportunities that the Gateway presents for science," said James Carpenter, a strategy officer in the European Space Agency's (ESA) Directorate of Human and Robotic Exploration.

What was discussed at the workshop was very much aligned with recent discussions within a European science community event held by ESA last December, Carpenter told Space.com.

"It is exciting to see the alignment of international ideas about the future of exploration and the opportunities that could be offered by the Gateway on our journey to the moon," Carpenter said.

Moondoggle?

Not everyone is thrilled with NASA's Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway plan.

The concept has received a thumbs-down from Robert Zubrin, president of the Colorado-based Pioneer Astronautics as well as founder and president of the public advocacy group, the Mars Society.

Zubrin did not attend the recent gathering, but in a recent Op-Ed piece he labeled the Gateway as a "boondoggle" that has a price tag of several tens of billions of dollars, at the least, and serves no useful purpose.

"We do not need a lunar-orbiting station to go to the moon, or to Mars, or to near-Earth asteroids. We do not need it to go anywhere," Zubrin said.

"There is nothing worth doing in lunar orbit, nothing to use, and nothing to explore," Zubrin said. "It is true that one could operate rovers on the lunar surface from orbit, but the argument that it is worth the expense of such a station in order to eliminate the two-second time delay involved in controlling them from Earth is absurd."

"We are on the verge of having self-driving cars on Earth that can handle traffic conditions in New York City and Los Angeles," Zubrin added. "There's a lot less traffic on the moon."

Leonard David is author of "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet," published by National Geographic. The book is a companion to the National Geographic Channel series "Mars." A longtime writer for Space.com, David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.