The 1st photo of the Milky Way's monster black hole has scientists over the moon. Here's why.

"What's more cool than seeing the black hole in the center of our own Milky Way?"

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

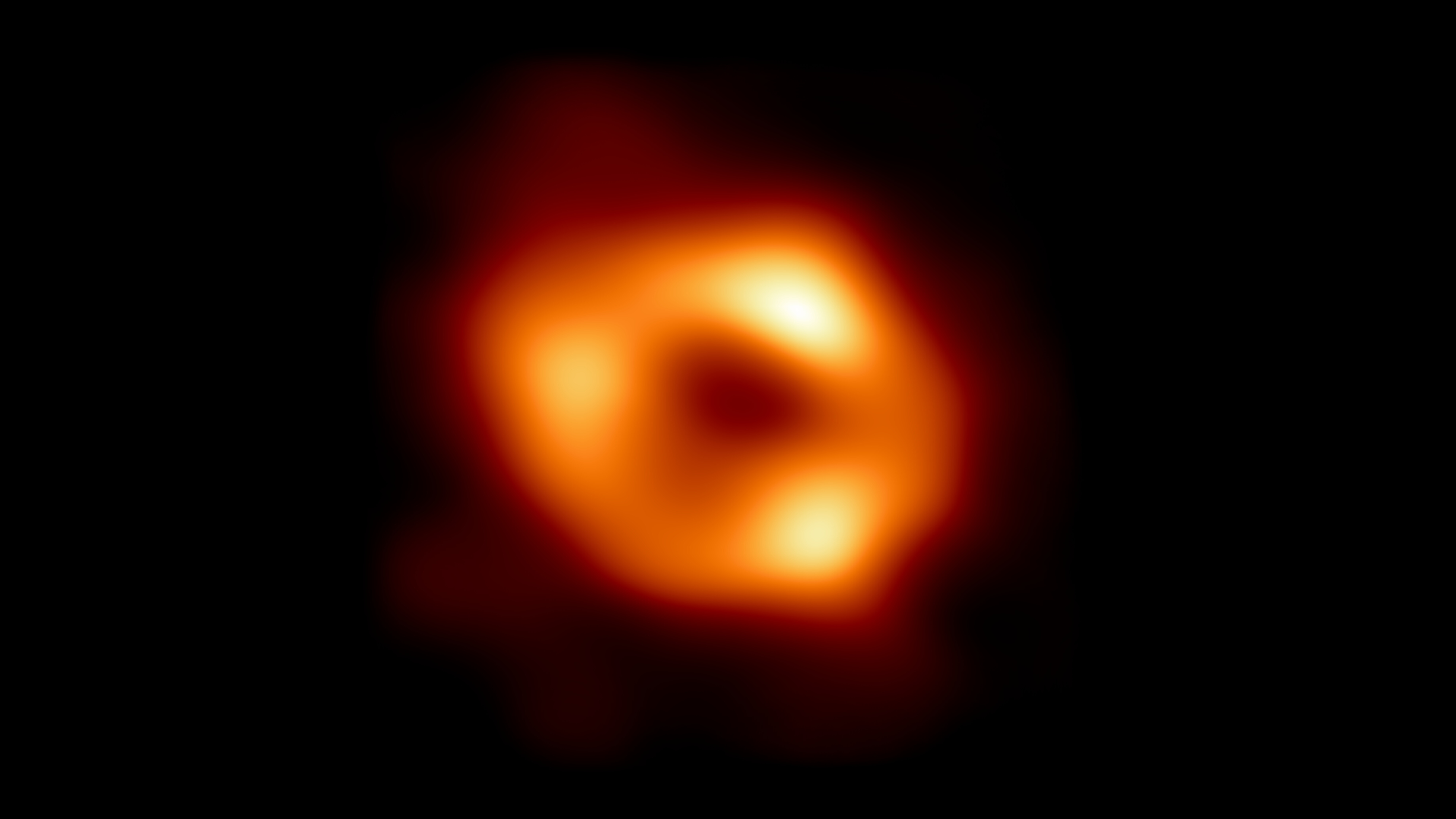

For decades, astronomers have wondered what's at the heart of the Milky Way galaxy. Today, scientists unveiled the first-ever photo of the supermassive black hole that lurks there, offering a completely new view of our home galaxy.

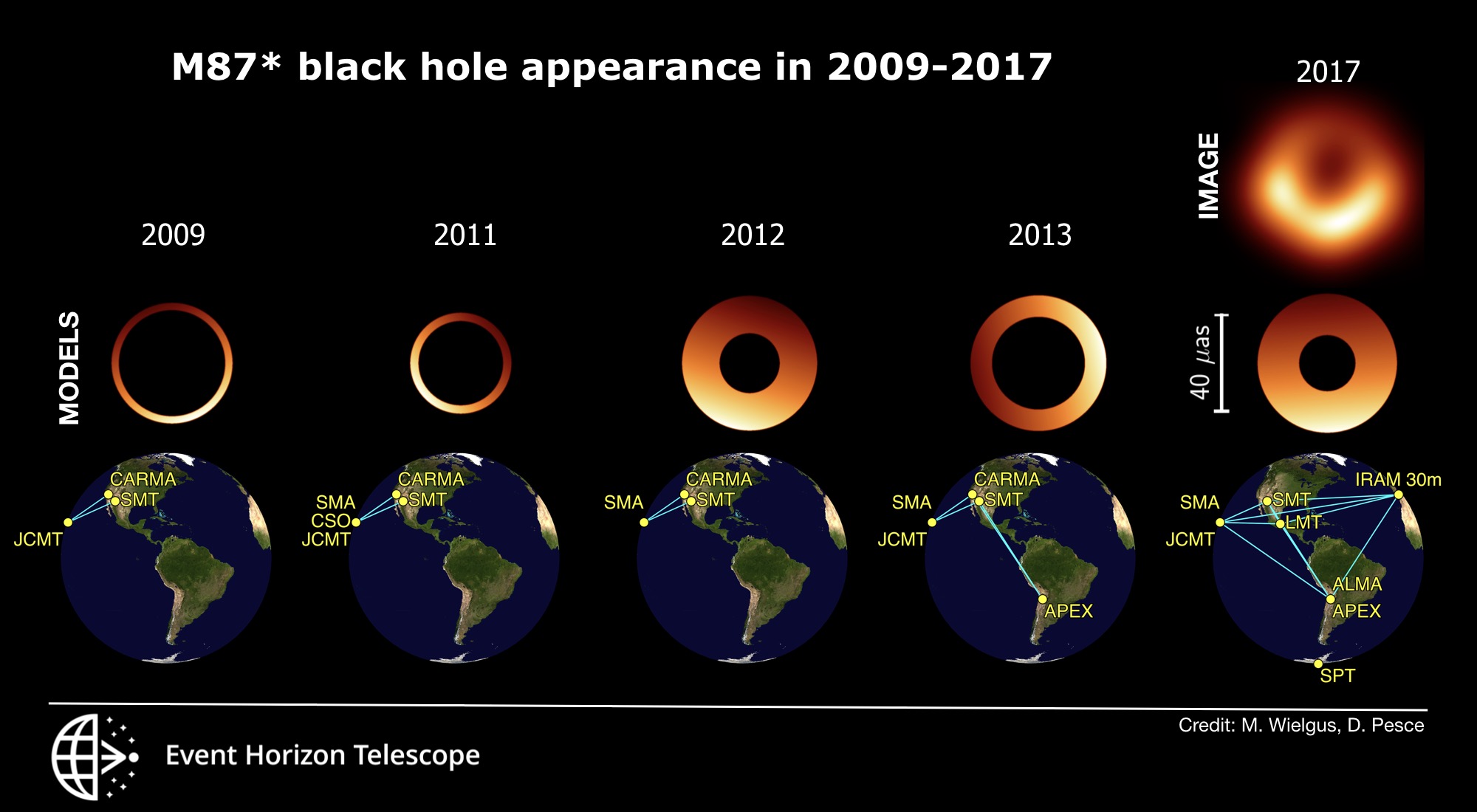

The historic image of what scientists call Sagittarius A*, captured by a worldwide telescope array called the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) and released Thursday (May 12), confirms a black hole in the heart of the Milky Way feeding on a hydrogen gas. EHT is most famous for capturing the first-ever black hole image of M87's supermassive black hole in 2019, but for scientists on the project, today's image is a still more remarkable milestone.

"I wish I could tell you that second time is as good as the first one imaging black holes. But that wouldn't be true. It is actually better," Feryal Özel, EHT modeling lead and a professor of astronomy and astrophysics at the University of Arizona, said during a press conference Thursday.

Sagittarius A* in photos: The Milky Way's monster black hole discovery in images

Related: 8 ways we know that black holes really do exist

Özel has been examining Sgr A*, as the black hole is nicknamed, for 22 years since her graduate student days. Imaging a second black hole with EHT shows the telescope's capabilities "wasn't a coincidence," Özel added, saying, "We now know that in both cases, what we see is the heart of the black hole — the point of no return."

It also felt like a reunion of old friends, she said, likening it to meeting an online friend in real life for the first time. "I kind of had an idea in my head about what it looked like; we were online chatting, and then I was like, 'Oh, you're real!'" Özel said, as the room laughed. "It's a very nice feeling."

Still, years of research could not fully prepare the team for the emotional impact of the discovery. "I remember seeing this and just kind of walking around in a daze," team member Michael Johnson, an astrophysicist with the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and lecturer in the Harvard University astronomy department, recalled to reporters.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"You look at that image," Johnson added, "and that hole in the center has 4 million solar masses. That's incredible."

Katherine Bouman, a Rosenberg scholar and assistant professor of computing and mathematical sciences at the California Institute of Technology, paid tribute to the range of disciplines and people it took to capture Sgr A*.

"It's pretty amazing what we were able to do, by bringing together people with lots of different expertise," Bouman said in the same press conference.

The EHT team had been observing Sgr A* long before today's reveal, but did not generate an image from the initial data. Sgr A* was considered a more difficult target to reveal than the black hole at the heart of M87, even though it is just half as far away.

That's because Sgr A* is a relatively lightweight supermassive black hole, with a mass of 4.3 million suns, with a more dynamic environment than the 6.5-billion-solar-mass M87, scientists have said. But now the new images show it was indeed possible to capture our galaxy's black hole.

"As a member of the collaboration, I'm just very proud that we've been able to not let all these challenges that were there from the beginning stop us from still going," Bouman said.

"We weren't afraid of the uncertainty, and all the missing information. We figured out ways to deal with it," she added. "And for that, I'm really, really happy, and I'm so honored to be able to work with the the people here. I think it's just super exciting. I mean — what's more cool than seeing the black hole in the center of our own Milky Way?"

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.