How the Event Horizon Telescope Hunts for Black Hole Silhouettes

The pioneering EHT links up multiple telescopes to create a virtual instrument the size of Earth.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The international Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) consortium, which aims to capture the first images of the edges of black holes, released its first results today (April 10). The secret of the project's success is how it links radio dishes across the globe to create a virtual telescope about the size of Earth.

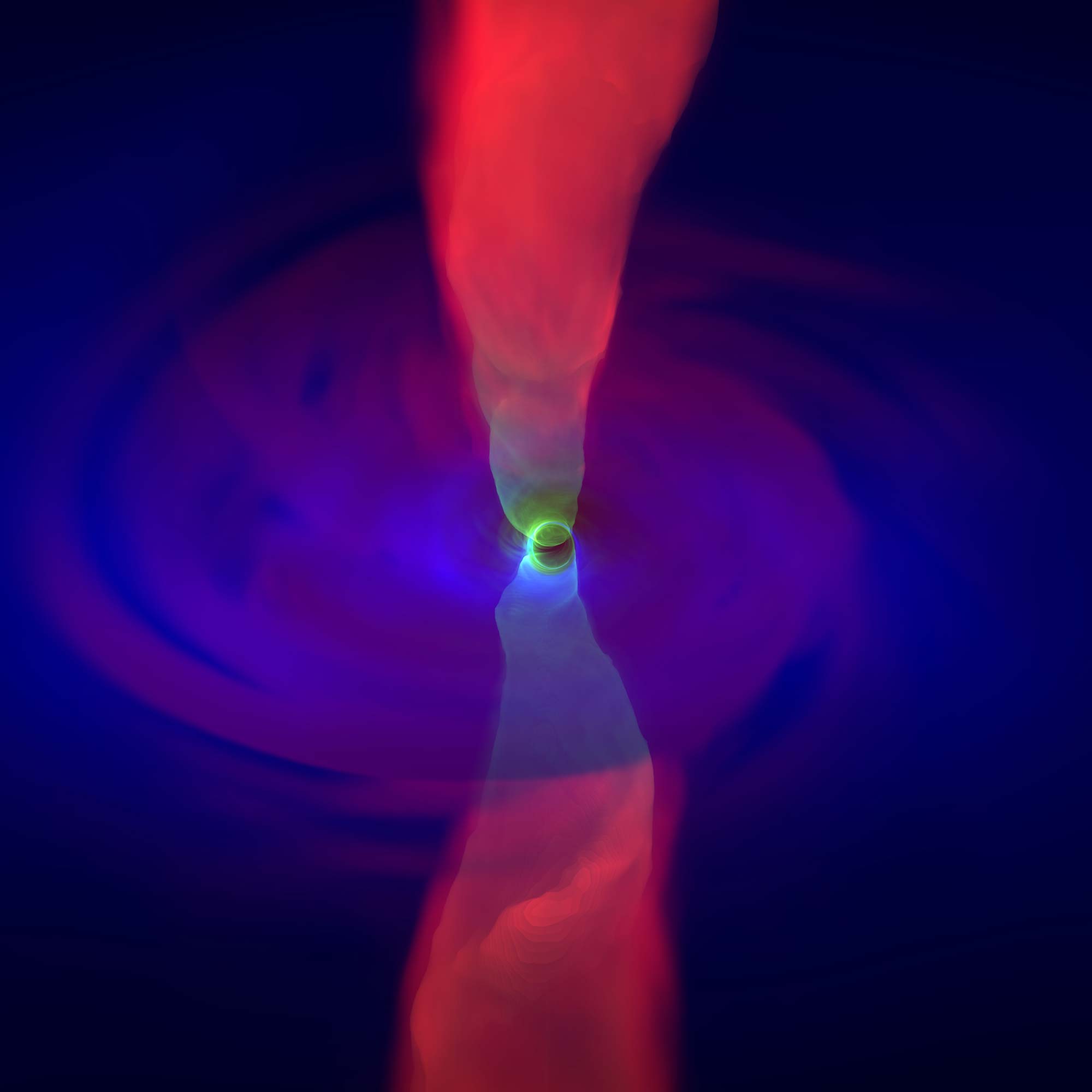

Black holes have gravitational pulls so powerful that, past thresholds known as their event horizons, nothing can escape, not even light. Although this means that black holes simply appear black, researchers still aim to capture the best photos they can of the objects' surroundings, which may glow with light. These images may reveal secrets about the mysterious structure of black holes and how they influence their environments.

The EHT aims to image supermassive black holes millions to billions of times the mass of the sun. For instance, the black hole Sagittarius A*, at the center of the Milky Way, is about 4.3 million times the mass of our sun, while the black hole at the heart of the M87 galaxy, which it has now released an image of, is about 6 billion solar masses.

Related: What Is a Black Hole Event Horizon (and What Happens There)?

EHT hunts for a shadow, or silhouette, against a bright background — the contours of the event horizon. Although the shadow of Sagittarius A* is about 30 times the diameter of the sun, this black hole lies about 26,000 light-years from Earth, and so, from our perspective, the shadow is about the same size as an orange would appear on the moon. The black hole at the heart of M87 is about 2,000 times farther away from Earth than Sagittarius A* and is thus even more difficult to see (though it is much bigger).

Moreover, black hole shadows are very dim when it comes to emitting the radio signals of interest to the EHT. Capturing enough energy from Sagittarius A* to light a 1-watt light bulb for 1 second would take one of the project's antennas about 250 million years.

Related: Images: Black Holes of the Universe

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To image these black holes, the EHT has radio telescopes around the world, from the United States to Mexico to Chile to the South Pole, observing the same targets at the same time. By collecting data in unison and stitching it together, this network can act like a single large telescope, one that, hopefully, has enough magnifying power to spot even distant, dim objects.

In 2017, the project included eight radio observatories, and three more are expected to join by 2020. "By having as many observatories as possible, you can improve the image," Avi Loeb, the chair of astronomy at Harvard University, told Space.com. (Loeb is not a member of the EHT team.)

To make sure that the radio telescopes act in sync, each one time-stamps its data with the help of atomic clocks that fire maser (microwave laser) beams at hydrogen gas. The atoms in this gas wobble at a precise frequency, much like swinging pendulums do in grandfather clocks. The atomic clocks that depend on these hydrogen masers are extraordinarily stable, losing only about 1 second every 100 million years.

Scientists have long had networks of multiple telescopes act like single large telescopes, a technique known as very long baseline interferometry. However, a key challenge with devising the EHT was operating with the relatively high-frequency radio waves needed to image these black holes.

"The rate at which data is recorded with the Event Horizon Telescope is at least an order of magnitude faster than old very long baseline interferometry, but with modern computers, this became feasible," Loeb said.

However, the biggest challenges the Event Horizon Telescope had to deal with may have been not technical, but social.

"I would say the biggest achievement of this project is being able to coordinate different observatories in different countries around the world," Loeb said. "Astronomers are quite competitive, and convincing hundreds of them to work together and figure out who the leader is, why that person should be the leader and how they all should get credit is quite a challenge."

- Black Hole Quiz: How Well Do You Know Nature's Weirdest Creations?

- Astronomers to Peer into a Black Hole for 1st Time with Event Horizon Telescope

- This Huge Black Hole Is Spinning at Half the Speed of Light!

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us