Looking back from beyond the moon: How views from space have changed the way we see Earth

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Alice Gorman, Associate Professor in Archaeology and Space Studies, Flinders University

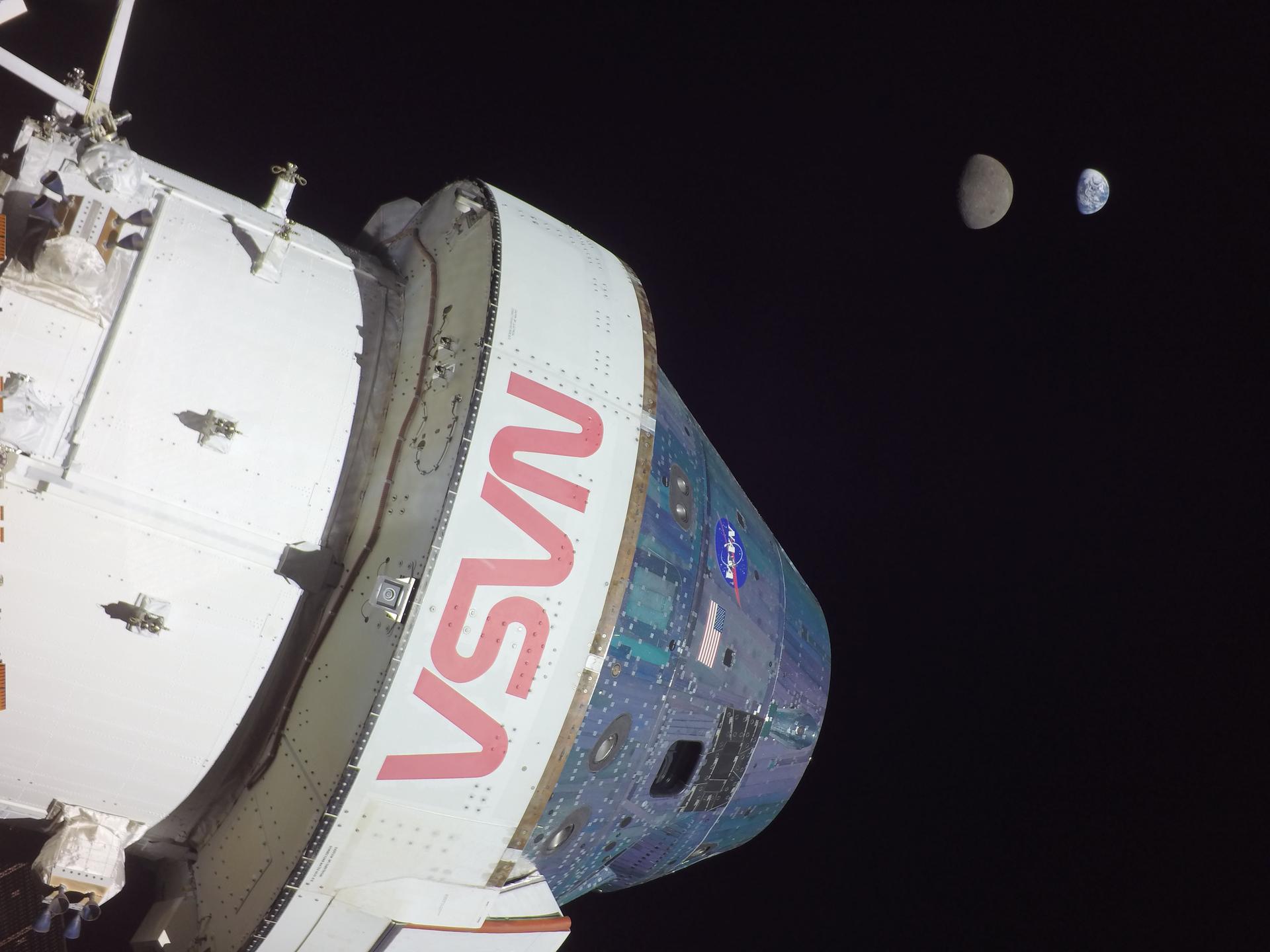

A photograph taken by NASA's Orion spacecraft has given us a new perspective on our home planet.

The snap was taken during the Artemis 1 mission, which sent an uncrewed vehicle on a journey around the moon and back in preparation for astronauts' planned lunar return in 2025.

We get pictures of Earth every day from satellites and the International Space Station. But there's something different about seeing ourselves from the other side of the moon.

How does this image compare to other iconic views of Earth from the outside?

Related: The 10 greatest images from NASA's Artemis 1 moon mission

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Earthrise

In December 1968, three astronauts were orbiting the moon to test systems in preparation for the Apollo 11 landing. When they saw Earth rise over the lunar horizon, they knew this was something special. The crew scrambled to find color film in time to capture it.

Photographer Galen Rowell called the resulting image "the most influential environmental photograph ever taken."

Six years earlier, biologist Rachel Carson’s book "Silent Spring" drew public attention to how human industries were harming terrestrial ecosystems. The book ignited the environmental movement and laid the ground for the reception of Earthrise.

The economist Barbara Ward, author of "Spaceship Earth" and one of the founders of sustainable development, said: "Above all, we are the generation to see through the eyes of the astronauts the astonishing 'earthrise' of our small and beautiful planet above the barren horizons of the moon. Indeed, we in this generation would be some kind of psychological monstrosity if this were not an age of intense, passionate, committed debate and search."

She saw Earthrise as part of the underpinning of a "moral community" that would enable a more equitable distribution of the planet’s wealth.

Blue marble

The last Apollo mission took place in 1972. On their way to the moon, the astronauts snapped the whole Earth illuminated by the sun, giving it the appearance of a glass marble. It is one of the most reproduced photographs in history.

Like Earthrise, this image became an emblem of the environmental movement. It showed a planet requiring stewardship at the global scale.

The Blue Marble is often used to illustrate the Gaia hypothesis, developed by James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis in the 1960s and '70s. The hypothesis proposes that Earth is a complex self-regulating system which acts to maintain a state of equilibrium. While the theory is not widely accepted today, it provided a catalyst for a holistic approach to Earth's environment as a biosphere in delicate balance.

The impression of a single, whole Earth, however, conceals the fact that not all nations or communities are equally responsible for upsetting the balance and creating environmental disequilibrium.

Pale blue dot

Our farthest view of Earth comes from the Voyager 1 spacecraft in 1990. At the request of visionary astronomer Carl Sagan, it turned its camera back on Earth for one last time at a distance of 3.7 billion miles (6 billion kilometers).

If Blue Marble evoked a fragile Earth, Pale Blue Dot emphasized Earth's insignificance in the cosmos.

Sagan added a human dimension to his interpretation of the image: "Consider again that dot. That's here. That's home. That's us. On it, everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you've ever heard of, every human being that ever was, lived out their lives."

Rather than focusing on Earth’s environment, invisible from this distance, Sagan made a point about the futility of human hatred, violence and war when seen in the context of the cosmos.

Tin can, grey rock, blue marble

Now, on the cusp of a return to the moon 50 years after Blue Marble was taken, the Orion image offers us something different.

Scholars have noted the absence of the photographer in Earthrise, Blue Marble and Pale Blue Dot. This gives the impression of an objective gaze, leaving out the social and political context that enables such a photograph to be taken.

Here, we know what is taking the picture — and who. The NASA logo is right in the center. It's a symbol as clear as the U.S. flag planted on the lunar surface by the Apollo 11 mission.

The largest object in the image is a piece of human technology, symbolizing mastery over the natural world. The spacecraft is framed as a celestial body with greater visual status than the moon and Earth in the distance. The message: geopolitical power is no longer centred on Earth but on the ability to leave it.

Elon Musk sent an identical message in photographs of his red Tesla sportscar, launched into solar orbit in 2018, with Earth as the background.

But there's a new vision of the environment in the Orion image too. It's more than the whole Earth: it shows us the entire Earth–moon system as a single entity, where both have similar weighting.

This expansion of the human sphere of influence represents another shift in cosmic consciousness, where we cease thinking of Earth as isolated and alone.

It also expands the sphere of environmental ethics. As traffic between Earth and the moon increases, human activities will have impacts on the lunar and cislunar environment. We're responsible for more than just Earth now.

Our place in the cosmos

Images from outside have been powerful commentaries on the state of Earth.

But if a picture were able to bring about a fundamental change in managing Earth's environment and the life dependent on it, it would have happened by now. The Orion image does show how a change of perspective can reframe thinking about human relationships with space.

It's about acknowledging that Earth isn't a sealed spaceship, but is in dynamic interchange with the cosmos.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook and Twitter. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Dr. Alice Gorman is an internationally recognized leader in the field of space archaeology. She is an Associate Professor in the College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences at Flinders University, where she teaches the Archaeology of Modern Society.

Her research focuses on the archaeology and heritage of space exploration, including space junk, planetary landing sites, off-earth mining, rocket launch pads and antennas.

She is a member of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, the Advisory Council of the Space Industry Association of Australia and the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

Her book "Dr. Space Junk vs the Universe: Archaeology and the Future" (2019) won the Mark and Evette Moran NIB People's Choice Award for Non-Fiction and the John Mulvaney Book Prize, awarded by the Australian Archaeological Association. It was also shortlisted for the Queensland Premier's Literary Awards, the NSW Premier's Literary Awards, and the Adelaide Festival Literary Awards.

Alice tweets as @drspacejunk and blogs at Space Age Archaeology.