The Beaver Moon lunar eclipse won't be a true 'blood moon,' but it may look red. Here's why.

The show starts early Friday (Nov. 19).

The Beaver Moon partial eclipse will probably turn the moon dark Friday (Nov. 19) even though it's not a true "blood moon."

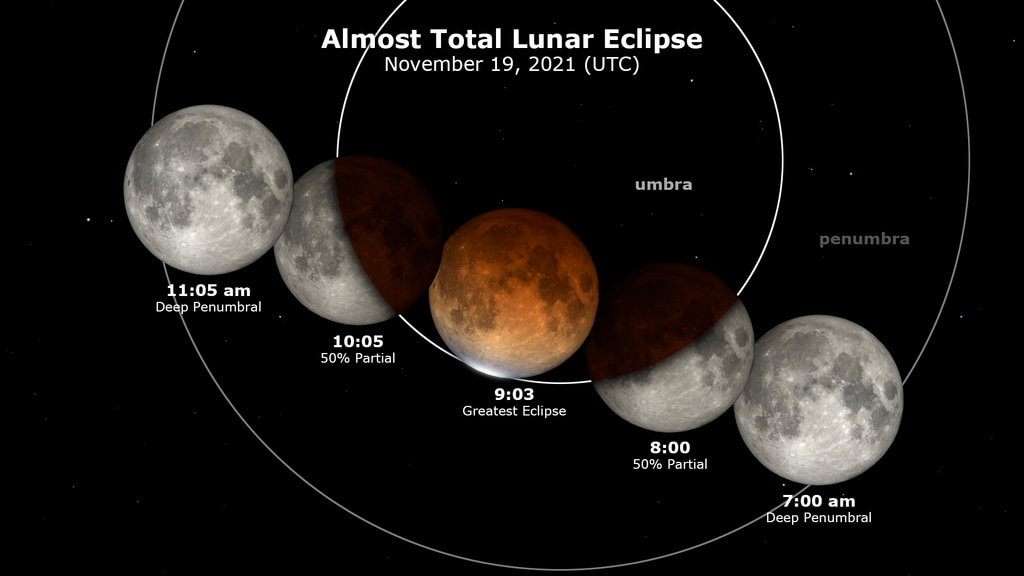

But to verify that for sure, be sure to tune in to the event. The Beaver Moon lunar eclipse will start at 1:02 a.m. EST (0602 GMT) and the eclipse will end at 6:03 a.m. EST (1203 GMT). You'll be able to watch the Beaver moon lunar eclipse online here and on the Space.com homepage.

Lunar eclipses happen when the moon passes into the shadow of the Earth and is at least partially covered by our planet's shadow. At its peak, the Beaver Moon will be 97% covered by the Earth's shadow, and will be well into the deepest part of the shadow (called the umbra). These two factors should just be enough to let the refracted sunlight from the edges from our planet cover our lunar neighbor in a red-brown hue. But because it won't be a total lunar eclipse, it's not considered a real blood moon.

Related: Beaver Moon lunar eclipse 2021: When, where and how to see it

"During a lunar eclipse, the moon turns red because the only sunlight reaching the moon passes through Earth's atmosphere," NASA said about the Beaver Moon eclipse. "The more dust or clouds in Earth's atmosphere during the eclipse, the redder the moon will appear. It's as if all the world's sunrises and sunsets are projected onto the moon."

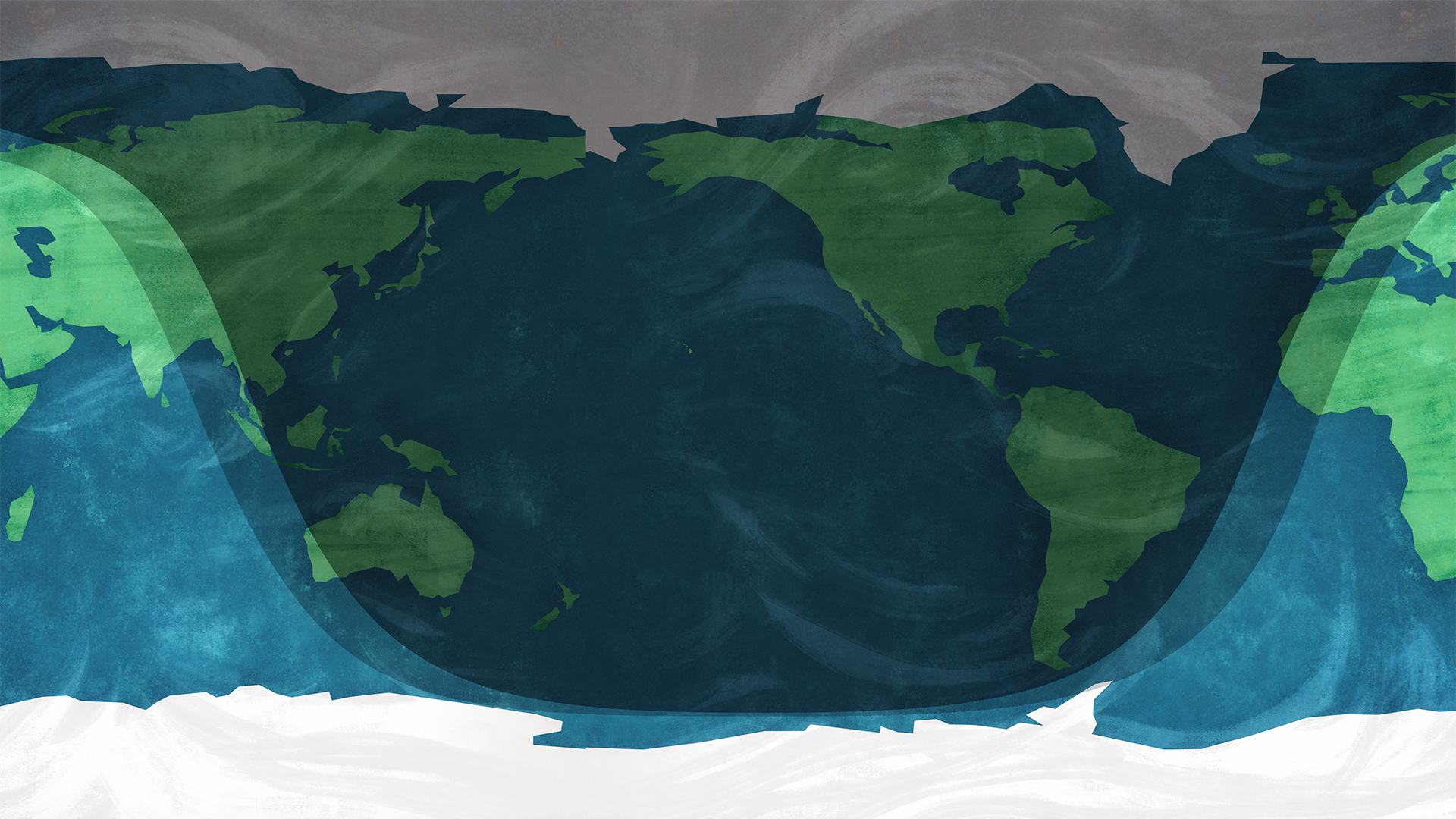

The event will be visible from North and South America, Australia, and parts of Europe and Asia. If you do have good weather, our guide on how to photograph a lunar eclipse, as well as how to photograph the moon with a camera in general, can help you make the most of the event. If you need imaging gear, check out our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography to help prepare for the next eclipse.

Do make sure that you're prepared to stay out in the cold, as the eclipse will be very long. The partial eclipse phase will last 3 hours, 28 minutes and 24 seconds, and the full eclipse for 6 hours and 1 minute, making it the longest partial eclipse in 580 years, according to Indiana's Holcomb Observatory. You can view the eclipse with no special equipment, just your eyes.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

NASA says this partial eclipse is ultra-long because the moon is almost at the farthest part from the Earth in its orbit (known as apogee), which means the moon is moving a bit slower through the shadow of Earth.

Also, the fact the eclipse is almost total means "the moon spends a longer amount of time in the Earth’s umbra than it would in a 'more-partial' eclipse," NASA stated.

Editor's Note: If you snap an amazing night sky picture and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photos, comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.