Hot on the Trail of Cosmic Rays

Themysterious origins of cosmic rays that slam into the Earth?s atmosphere couldsoon be revealed, thanks to a better ground-based sensor that costs less thanballoons or satellites.

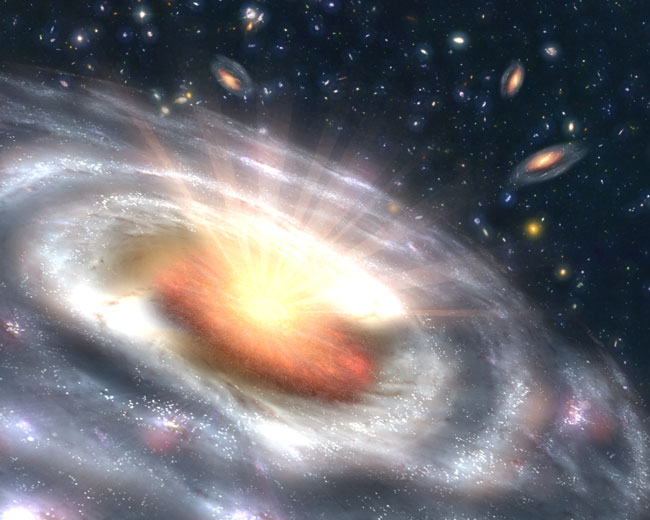

Cosmic raysare thought to come from either the centerof the galaxy or a nearby supernova, and knowing which is true will helpastrophysicists paint a more accurate picture of the cosmos.

"Cosmicrays are not a spectator phenomenon in the galaxy — they have a role ingalactic dynamics," said Scott Wakely, a University of Chicago physicist. "To understand thegalaxy in a full sense, you need to understand cosmic rays."

Thatunderstanding depends on ground and space-based instruments. Satellites andballoons first detect a blue flash — known as Cerenkov radiation — when cosmicrays smash into the upper atmosphere and release energy.

The cosmicray particles then break into a shower of smaller pieces and produce a secondblue flash. Ground sensors usually only detect the second flash.

Tens ofthousands of particles may bombard an area the size of a small parking lot onEarth daily, while rarer high-energy particles strike less than once a year in thesame area. Satellites and balloons do a better job of detection by rising abovethe atmosphere, but they can only cover a small area.

"A$400 million satellite is only a couple particles per year, and you wanthundreds of thousands," Wakely told SPACE.com. "You always want tolook for new ways to do this."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Wakely setout with colleague Simon Swordy, a physicist at the University of Chicago, to create a ground-based instrument that could detect boththe first and second blue flashes. The instrument will have roughly 10 timesthe resolution and power of current ground-based detectors.

Scientistscan use information from both blue flashes to identify a particle as a certainelement and maybe even its origin. For instance, some elements will more likelycome from the fieryoutburst of a supernova.

"Wecan say that was iron or that was uranium," noted Wakely. "Those arethe kinds of data you need to make progress in this business."

No onethought ground-based instruments could detect the first blue flash, untilWakely and Swordy proposed the idea with other colleagues in 2001. A team ofresearchers in Namibia confirmed the concept using atelescope array called HESS. Wakely later made his own observations using atelescope array called VERITAS.

"Thatwas direct evidence that it [the technique] works," said Wakely. "Thegoal of this [new] instrument is to combine large area detection with the highprecision of space-based sensors."

An improvedinstrument could also help solve at least one mystery about the energy range ofcosmic ray particles. Higher energy particles — such as those from the nucleiof heavy elements like iron — are rarer than common, lower-energy particlessuch as protons. But physicists have puzzled over a sudden drop-off infrequency of high-energy particles at a certain point in the energy spectrum,labeling the strange kink "the Knee" because of its shape.

Someresearchers suggest that supernovas which they claim produced all the cosmicrays suddenly run out of energy at "the Knee," and a new source ofcosmic rays takes over on the other side. Others think that a new model ofphysics takes over that is beyond current scientific understanding, but no oneknows for sure, without more measurements of high-energy particles from"the Knee" region.

If all goeswell, Wakely and Swordy plan to submit a proposal in three years to build theinstrument they are designing. The National Science Foundation has alreadygiven a five-year, $625,000 grant to start drawing up the concept.

- VIDEO: Supernova: Creator/Destroyer

- Top 10 Strangest Things in Space

- Astronomers Describe Cosmic Pinball Machine

Jeremy Hsu is science writer based in New York City whose work has appeared in Scientific American, Discovery Magazine, Backchannel, Wired.com and IEEE Spectrum, among others. He joined the Space.com and Live Science teams in 2010 as a Senior Writer and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Indicate Media. Jeremy studied history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania, and earned a master's degree in journalism from the NYU Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. You can find Jeremy's latest project on Twitter.