Don't Miss the Super Blood Wolf Moon Eclipse Tonight! It's the Last Until 2021.

Update for 3 a.m. EST, Jan. 21: The total lunar eclipse of 2019 has ended. See our full story here! See more photos here!

Original Story: The moon will pass through Earth's shadow tonight in the only total lunar eclipse of 2019 and you won't want to miss it! If you do, you'll have to wait two years for the next one. And if you're in North America, you'd have to wait even longer, until 2022!

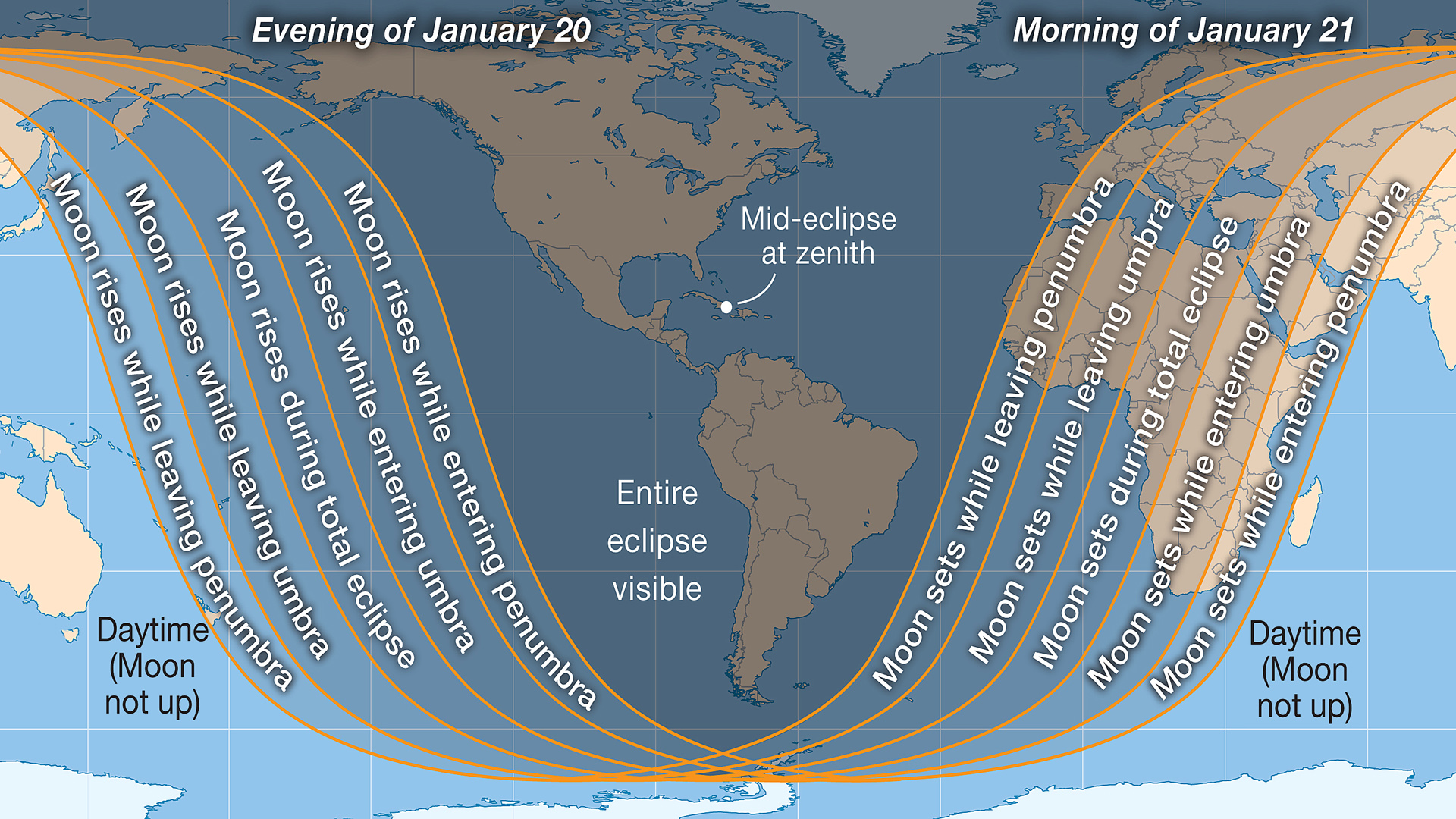

Skywatchers in North America will get a celestial treat late Sunday (Jan. 20) and early Monday (Jan. 21), when the moon goes into eclipse and turns blood red. While the weather will be very cold for many in North America, astronomers say to bundle up and check out the sight now. That's because the next total eclipse won't happen until 2021, and North Americans will have to wait until 2022 for a blood moon to be visible from their location. Tonight's total lunar eclipse is occurring while the moon is near it's closest point to Earth for the month, which some call a "supermoon." Since January's full moon is also known as the Wolf Moon, that's led some to christen tonight's lunar event a Super Blood Wolf Moon.

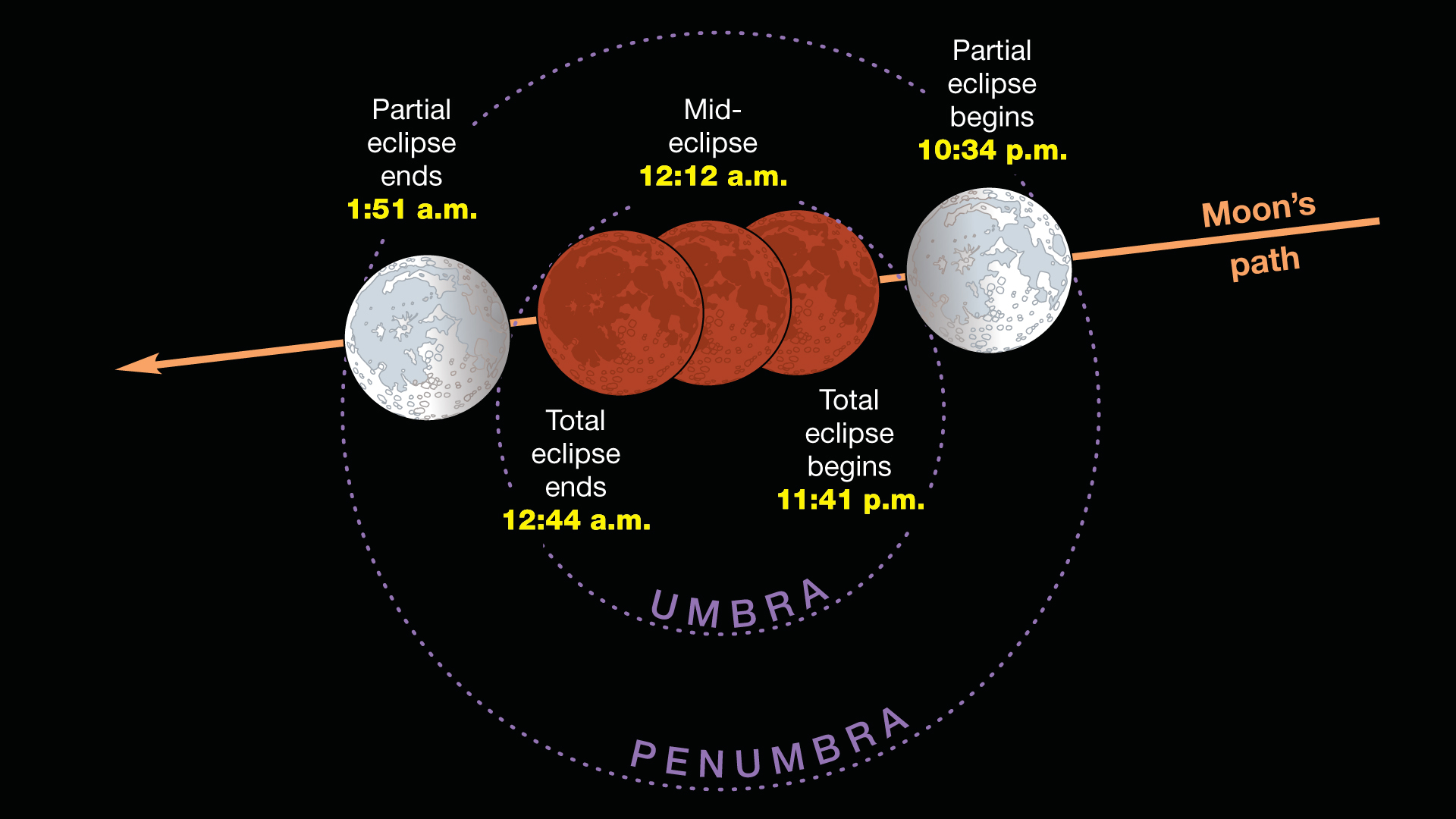

The partial stage of the lunar eclipse begins at 10:34 p.m. EST Sunday night (0334 GMT Monday morning) with the total eclipse beginning at 11:41 p.m. EST (0441 GMT Monday morning). Totality lasts for about an hour, and then the moon will exit the partial eclipse phase at 1:51 a.m. EST Monday morning (0651 GMT). Webcasts are available at Slooh.com, timeanddate.com and several other sites, as well as at Space.com, courtesy of Slooh. [Super Blood Moon Lunar Eclipse of 2019: Complete Guide]

Lunar eclipses happen when the moon passes into the Earth's shadow. During a total eclipse, the moon passes so deep into the shadow that any light reaching its surface only comes from the edge of Earth, where sunrises and sunsets are taking place. That light falls on to the moon and turns it red, or sometimes appearing as a more ruddy brown depending on how dusty your local atmosphere is (among other factors).

Because of the geometry of Earth, sun and moon, sometimes there are periods during which no lunar eclipses happen for a long time. This situation happens every 19 years, David Dundee, an astronomer at the Tellus Science Museum in Cartersville, Ga., told Space.com.

"There are actually more than one set of patterns all running concurrently," he wrote in an email. "[It all] has to do with how the orbit of the moon oscillates north and south. When the orbit passes through the plane of the Earth's orbit, this is a 'node'; this is when an eclipse can happen if the moon phase is correct." So in other words, the moon won't experience a total eclipse for a while because the orbital nodes of the moon aren't happening at the right time for the full moon to pass through the Earth's shadow.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The sun also goes through a cycle of lulls for solar eclipses, which occur when the moon passes in front of the sun. However, solar eclipses are much more complicated — and not only because they require special protection for your eyes. While skywatchers coast to coast in the United States got the chance to see a solar eclipse in 2017, the shadow of the moon is so small that it a total lunar eclipse passes over a band that only stretches 70 to 100 miles (112 to 161 kilometers), Dundee said. Total lunar eclipses, by contrast, are visible over an entire hemisphere of Earth.

Whether you watch this weekend's lunar eclipse by webcast or in person, Dundee has some tips about what to look for.

"Look for the edge of the shadow covering the moon. It will be fuzzy or ragged," he said. "This is because of the Earth's atmosphere; [it] will cause the edge of the shadow to be ill defined. Plus as the eclipse progresses, you can see the shape of the shadow is round, a consequence of living on a round planet. Finally, the color of the fully eclipsed moon depends on the amount of dust in the Earth's atmosphere and the cloud cover on other parts of the Earth."

No special equipment is needed for the lunar eclipse — just your own eyes and some warm clothing. If you have binoculars or a telescope handy, you might see a little more detail on the lunar features, but mostly you can expect more mottled red inside the viewfinder.

Editor's note: If you snap an amazing photo of the January 2019 total lunar eclipse that you'd like to share with Space.com and our news partners for a possible story or image gallery, send comments and images in to: spacephotos@space.com.

Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.