Secrets from the Far Side of the Moon

The moon shows us its smiling "Man in the Moon" face every month, illuminated by the sun to varying degrees over the course of its orbit around us. However, thanks to its orbital dynamics, we only ever get to see that one hemisphere from Earth. The other hemisphere — the "far side" — is constantly concealed from us.

Well, that's not strictly true. Libration, which is the gentle "wobbling" of the moon in the sky caused by changes in its position in its elliptical (i.e. non-circular) orbit around Earth, mean we can catch glimpses of small slivers of the far side — we can actually see 59 percent of the moon's surface from Earth at different times of the year. But until the first space missions to the moon flew around our natural satellite, what lay beyond on the far side was a mystery.

It's often mistakenly thought that the far side of the moon is in darkness. Rather, it experiences day/night cycles just like the near side. When we see half of the moon being illuminated by the sun, giving it a half or crescent shape in the sky, half of the moon on the far side is being illuminated at the same time. When the moon is new, the far side is in full daylight instead. When the moon is full, it's night-time on the far side. [China's Chang'e 4 Moon Far Side Mission in Pictures]

The reason we only see the one face is because of a phenomenon known as "tidal locking." The moon rotates on its axis roughly once every 27 days, which is the same amount of time it takes to orbit the Earth. This means it is rotating at a rate that means we always see the same face, more or less, as it moves around Earth.

"There are two weeks of daylight and two weeks of night on every spot on the lunar surface," Charlie Duke, who was the Lunar Module pilot on the Apollo 16 mission, told All About Space. "It was early morning during the moon day at the Apollo 16 landing site, which was called Descartes. We were the fifth mission to land on the moon, and I can say that it really is a dramatic place."

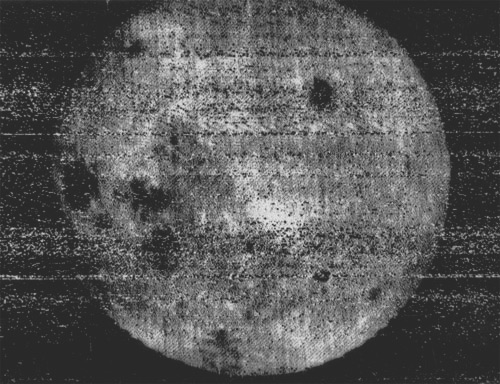

Our first glimpse of the mysterious far side came early in the space race, courtesy of the Soviet Union's Luna 3 spacecraft almost 60 years ago. In 1959, barely two years after placing Sputnik 1 in orbit, Russian engineers managed to send the spacecraft, which was crude by today's standards, into orbit around the moon and, for the first time, we got a good look at the mysterious far side.

Luna 3 took 29 film images of the far side in total, which were photographically developed, fixed and dried on board — remember, this was long before multi mega-pixel cameras. Ironically, the film used had been stolen from American spy balloons, as it had to be sturdy and radiation-hardened.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The spacecraft, using a combination of two camera systems, one wide-field and one narrow-field but higher resolution, and a crude onboard scanner, could then transmit the processed images, which were spot-scanned from the photographs, back to the receiving station in the former Soviet Union. Although only 17 of the 29 taken were transmitted successfully back to Earth, of which six were considered good enough for publication, they proved to be a revelation.

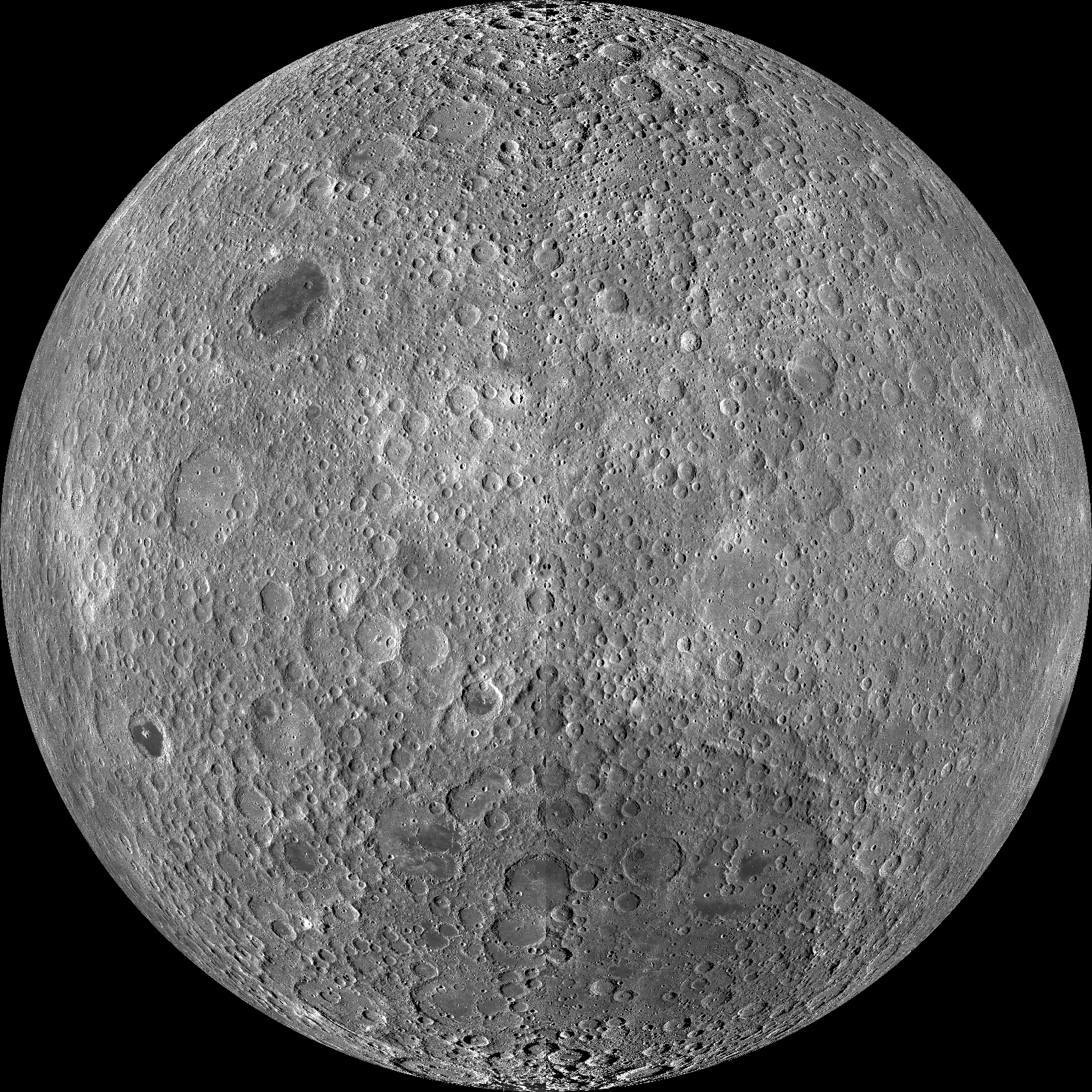

Those six images covered 70 percent of the far side and opened a whole new perspective on the lunar surface. It was almost immediately evident that the dark patches that make the face of the Man in the Moon on the near side are almost completely absent on the far side. These dark patches are basaltic plains called "mare" created by volcanic activity on the moon billions of years ago. Instead, the far side was littered with craters, even more so than the near side, and some of those craters were the size of small countries. The Soviets started naming many of the features they were seeing for the first time, an act which caused some controversy in what was known as the height of the Cold War era.

We already had an inkling of one of those vast new craters, which is actually one of the very few mare on the far side. The subtlest hint of Mare Orientale, one of the largest impact craters known, seen on the limb of the moon, had been known of since its "discovery" by Julius Franz in 1906 and can be seen during good librations when that portion of the moon swings around towards us. [The Moon: 10 Surprising Lunar Facts]

The view from Luna 3 showed how vast an impact crater Orientale was, resembling a bullseye. It was almost 560 miles (900 kilometers) across, pretty much the length of the United Kingdom give or take, and was caused by an asteroid impact, thought to be around 40 miles (64 km) wide just under 4 billion years ago. the resulting giant crater, termed an "impact basin," was subsequently filled with volcanic lava.

In 1965, another Soviet mission, Zond 3, flew by the moon with a far better camera than Luna 3 possessed and with the ability to conduct more detailed science observations, including spectroscopy. Zond 3 produced 23 very detailed photographs of the lunar far side, which enabled one of the first detailed maps of the entire lunar surface to be constructed.

In the meantime, NASA was progressing its Apollo Program at a phenomenal rate. Following the declaration by President Kennedy that the U.S. would place a man on the moon and return him safely to the Earth by the end of the 1960s, by December 1968 NASA was ready to send three people — Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and Bill Anders — all the way around the moon and back for the Apollo 8 mission. They became the first humans in history not only to escape from low Earth orbit but also to see the elusive far side.

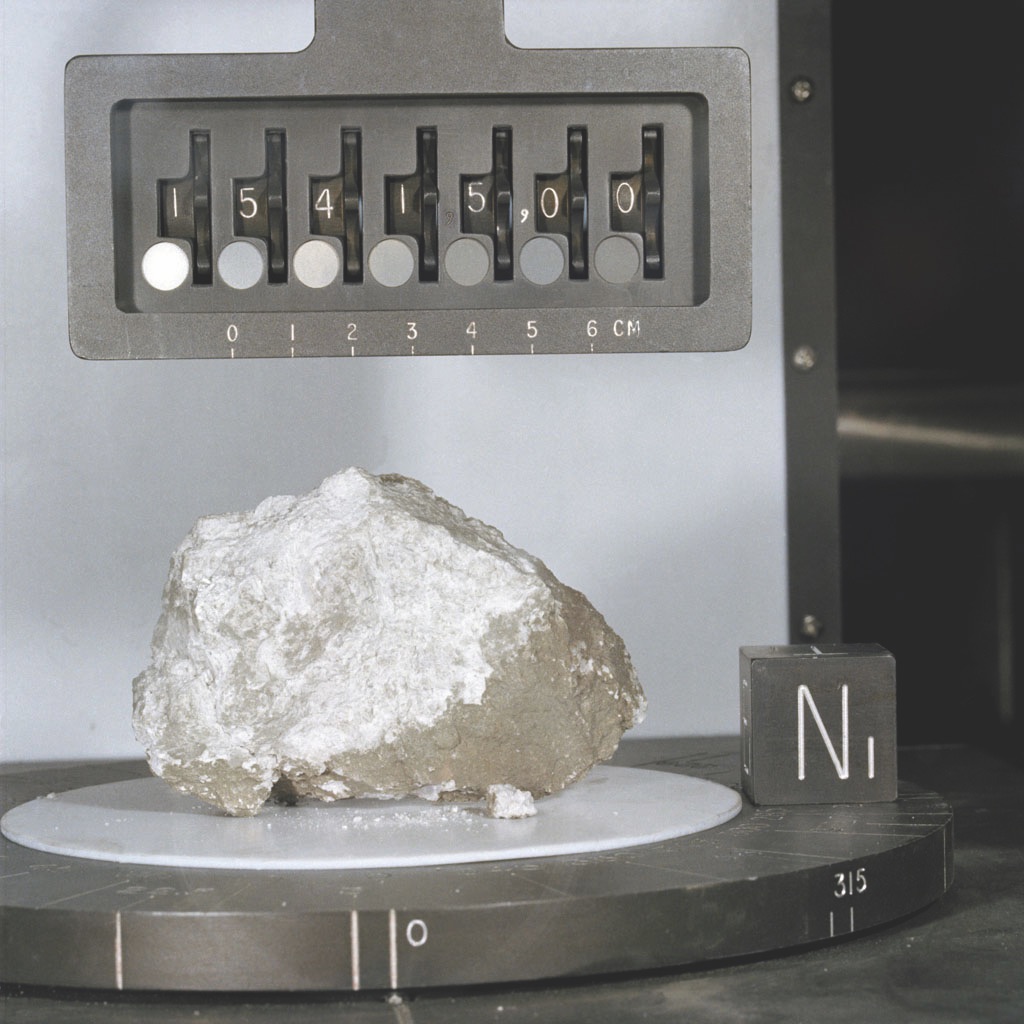

This is how Lovell famously described the lunar surface: "The moon is essentially gray, no color, looks like plaster of Paris or sort of a grayish beach sand. We can see quite a bit of detail. There's not as much contrast between that and the surrounding craters. The craters are all rounded off. There's quite a few of them, some of them are newer. Many of them look like — especially the round ones — look like [they were] hit by meteorites or projectiles of some sort." [Apollo 8: NASA's First Crewed Trip Around the Moon in Pictures]

When the Apollo 8 spacecraft flew around the far side of the moon, the signal to Earth was cut off for around 10 minutes. This loss of signal was a daunting time for the flight crew and mission control; Apollo 8 was alone and truly cut off from Earth, venturing where no human had ever gone before. As the astronauts came back around from the far side, a collective sigh of relief was breathed by many of the flight team at mission control in Houston.

Charlie Duke describes what it was like to be flying over the far side of the moon.

"The computer told us that we were out of contact with the Earth and that we had loss of signal," he says. "Then, all of a sudden, there wasthe sunrise, it was the most dramatic sunrise I’veever seen. In Earth orbit, you see the sun's glow onthe horizon or the planet’s atmosphere, and it getsbrighter and brighter. The moon is different, though—there’s instant sunlight with long shadows on thelunar surface. The far side of the moon was veryrough back there. I would not have wanted to landon the backside of the moon."

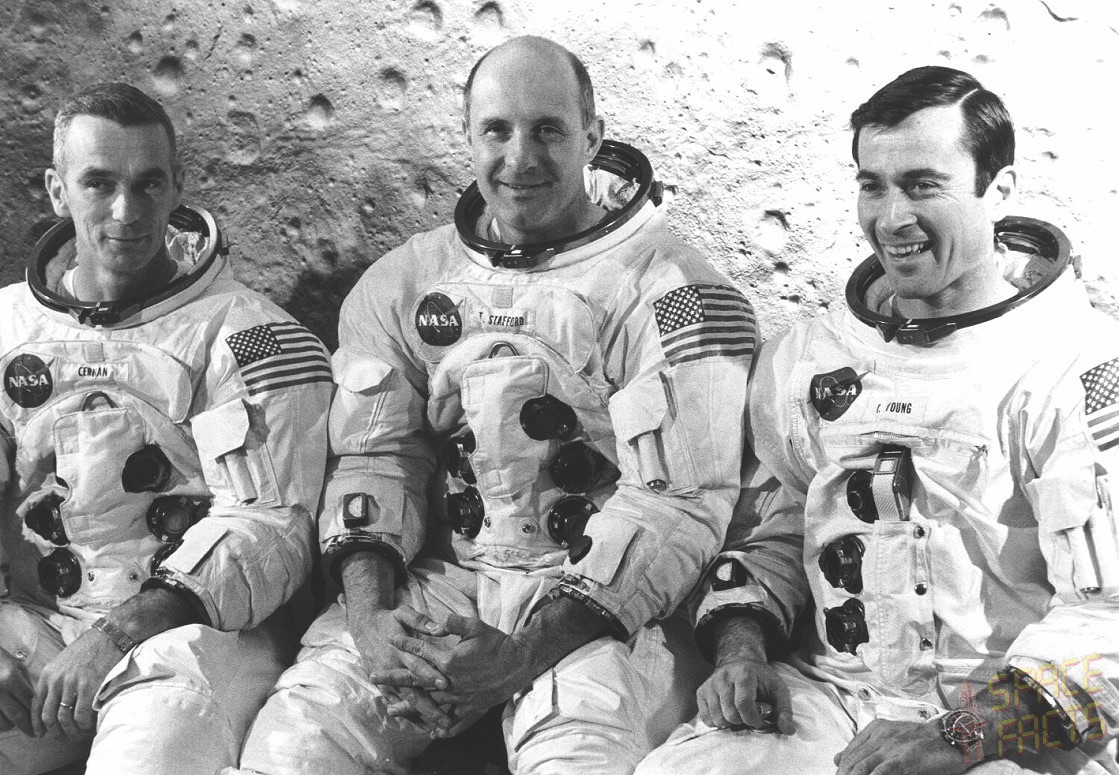

After the success of Apollo 8, Apollo 9 went back to vital low Earth orbital testing of the lunar module, so the next astronauts to visit the far side were Gene Cernan, John Young and Tom Stafford on board Apollo 10 in May 1969, just two months before the historic landing of Apollo 11.

However, while flying over the far side of the moon, the trio of astronauts encountered something strange, which in the last few years NASA has been forced to re-explain thanks to conspiracy theory documentaries airing on U.S television. The facts had been well known since the 1970s.

These "strange events" on Apollo 10 were manifest in the form of some very odd sounds. The radio systems on board the Apollo spacecraft were crude by modern standards, though state of the art at the time. The command and lunar modules were relatively noisy environments according to most of the astronauts, with bumps and bangs combined with the whirring of fans and engine noise. What the Apollo 10 crew heard through the radio systems baffled them. They described it as being almost like that made by an electronic instrument called a theremin, often used in creepy science fiction B-movies of the 1950s and 60s, as well as on the Beach Boys song "Good Vibrations." Research has since proven that the sound was nothing more than an interference effect from those 1960s radio communications systems on board. [Lunar Legacy: 45 Apollo Moon Mission Photos]

With the onset of the moon landings, two astronauts would travel to the surface while a third remained onboard the command module to orbit the moon alone, though all of them got chance to orbit the moon and see the far side before landing. The solo orbital journeys of Michael Collins (Apollo 11), Dick Gordon (Apollo 12), Stuart Roosa (Apollo 14), Al Worden (Apollo 15), Ken Mattingly (Apollo 16) and Ron Evans (Apollo 17), who were the unsung heroes of the Apollo missions, are some of the bravest feats ever achieved by astronauts. They would spend days making quite detailed lunar observations from orbit, mapping features nobody had ever seen before.

Al Worden is often quoted as saying that his time alone was some of the best he had during the Apollo 15 mission.

“It was nice to be rid of those guys, as you can imagine. Being stuck in something the size of a family car for over a week, it got pretty crowded up there. Once Dave [Scott] and Jim [Irwin] left, I felt like I had some real space to start to do my important work of mapping the lunar surface. But the far side, the views at certain times, when the sun and the Earth are blocked out, are like nothing you could imagine. The sheer number of stars you see is incredible; it's like a sheet of white, and you know that every single one of them is a sun in its own right."

A question often asked of the Apollo astronauts and flight teams is, Why were all the missions just to the near side? [Moon Master: An Easy Quiz for Lunatics]

"We wanted to be in contact with the Earth, so we weren't able to land on the far side of the moon," says Charlie Duke. Should something have gone wrong while the astronauts were on the surface, they would not have been able to communicate directly with Earth. This would not be such a problem today, as satellites could be put into lunar orbit to relay communications.

The far side is of growing interest to scientists, and potentially future planned human missions. Indeed, the possibilities for the far side of the moon are vast. For many decades, the astronomical and scientific community has wanted to put radio telescopes and optical telescopes on the far side. Observatories on the far side would be shielded from not only man-made radio interference from Earth, but also the glare of daylight on our planet. The telescopes could be built inside craters to avoid solar radiation, and would provide us with an unprecedentedly clear insight deep into the far reaches of the universe.

We also have little true understanding of the processes that make the far side so vastly different in appearance to the near side. Why it is so scarred with impact craters and so lacking in volcanic mare is even more puzzling when you consider that when the moon formed, it was much closer to Earth, and may not have necessarily been tidally locked at that time, meaning there would have been nothing special about the hemisphere we dub the far side.

Today, NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter has mapped the near side and far side of the moon in exquisite detail. And China just launched the robotic Chang'e 4 mission, which will make the first-ever landing on the lunar far side in early January. When humans do eventually return to the moon, the far side must be a goal for a landing. Understanding it will give us more insight into not only the moon's past, but also perhaps the moon's relationship with Earth our own past.

This article was provided by Space.com's sister publication All About Space, a print magazine dedicated to astronomy, space exploration and the night sky. Sign up for the All About Space newsletter for news and subscription details! Follow us @Spacedotcom or Facebook. This version of the story published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Gemma currently works for the European Space Agency on content, communications and outreach, and was formerly the content director of Space.com, Live Science, science and space magazines How It Works and All About Space, history magazines All About History and History of War as well as Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics (STEAM) kids education brand Future Genius. She is the author of several books including "Quantum Physics in Minutes", "Haynes Owners’ Workshop Manual to the Large Hadron Collider" and "Haynes Owners’ Workshop Manual to the Milky Way". She holds a degree in physical sciences, a Master’s in astrophysics and a PhD in computational astrophysics. She was elected as a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 2011. Previously, she worked for Nature's journal, Scientific Reports, and created scientific industry reports for the Institute of Physics and the British Antarctic Survey. She has covered stories and features for publications such as Physics World, Astronomy Now and Astrobiology Magazine.