Pioneering Solar Scientist Eugene Parker Gets His Day in the Sun

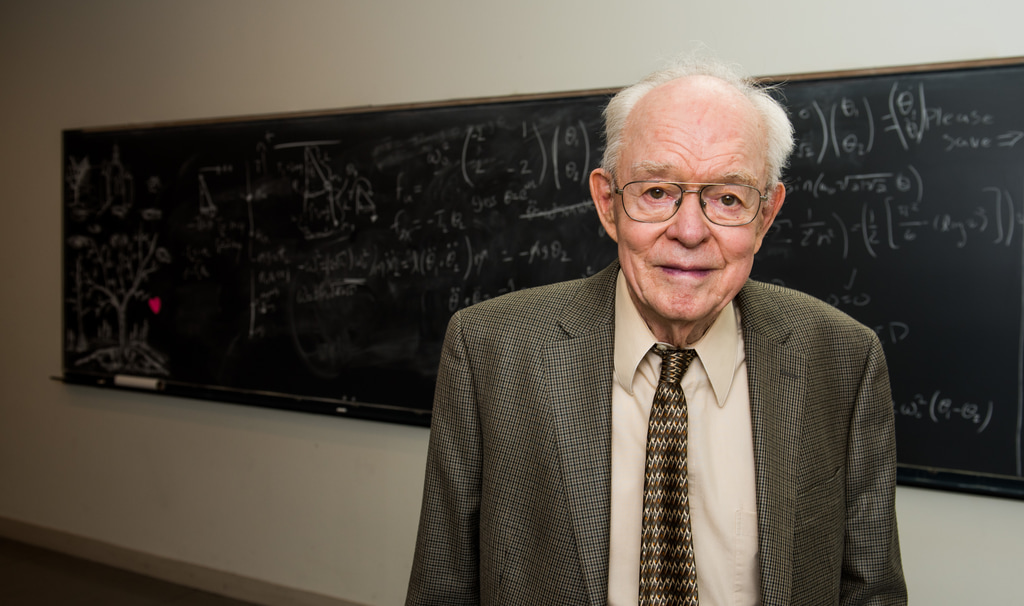

NASA's Parker Solar Probe, set to launch this weekend, is the first spacecraft ever named after someone still living: Eugene Parker, the groundbreaking sun scientist whose theories redefined how we understand our nearest star.

Parker's pioneering work at the University of Chicago in 1958 proposed the existence of the solar wind, the stream of charged particles constantly released by the sun that flows through the solar system at close to 1 million mph (1.6 million km/h).

Experts doubted his theory, according to NASA, until the existence of the solar wind was proved in 1962 using data from the Mariner 2 mission to Venus, which was the first probe to visit another planet. Since then, Parker's work has pushed solar research forward, as well as our understanding of magnetic fields and other key areas. [In Photos: NASA's Parker Solar Probe in the Clean Room]

"Why Dr. Parker? Because this mission is there because of him," Nicola Fox, a Parker Solar Probe project scientist from Johns Hopkins University in Maryland, said during a news conference July 31. "He's really the father of this whole physics branch. Heliophysics is the study of the sun and what it does to the solar system, and the way it does that is the solar wind. Gene was the one who predicted it and profoundly changed the way we thought about how our star worked."

"Without Gene, there probably would not have been the same amount of passion and the same amount of 'let's go do this' that has kept [visiting the sun] such a high priority for 60 years while we waited for that technology to really be there to be able to do this really daring mission," she added.

Finally, technology and materials research has progressed enough to send a spacecraft up close to the sun to see how it all works. The Parker Solar Probe is set to provide the best-ever data on many of the questions his work has raised during seven years of investigation, diving closer and closer to the sun before eventually passing through its wispy outer atmosphere, called the corona.

"Frankly, there's no other name that belongs on this mission," Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA's science mission directorate, said during a briefing yesterday (Aug. 9). "I did a tally with my team and basically said how many missions do we have in our mission portfolio that directly are involved in looking at things and measuring scientific phenomena that are predicted by Gene's papers — and the answer is 35."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Thirty-five missions, both here in our environment, in heliophysics missions, but also in astrophysics and missions in planetary sciences," he added.

Parker himself had the chance to discuss the mission during the news conference on July 31, taking the stage at University of Chicago where he's a professor emeritus.

"Sometimes people sound a little puzzled as to why do you want to go to such a hotspot?" Parker said. "And the answer is because we have reason to believe that interesting things are going on."

Some of those puzzles, which the Parker Solar Probe will address: It will examine how the solar wind is accelerated so powerfully out of the sun; help scientists learn how the sun's corona is so much hotter than its surface; and reveal connections between changes in the sun's magnetic field and the space weather felt on Earth.

"I have always said that since this is a mission into unknown territory, we have to be prepared for some surprises," Parker said. "Things that we never thought of, or things that we thought of but were not correct." He said that the way the solar wind and the corona is heated is the biggest mystery he's looking forward to finding out more about, especially as solar activity picks up. (The sun is in a comparatively placid part of its 11-year cycle, but as the Parker Solar Probe observes it will be whipped up into its sunspot-sporting, plasma-slinging active phase.)

The probe will launch during a window starting at 3:33 a.m. EDT (0733 GMT) Saturday, flying on the powerful Delta 4 Heavy rocket from Cape Canaveral in Florida — and eventually becoming the fastest-moving human-made object, researchers said during the briefings. It will swing through its first close approach to the sun on Nov. 5, after a pass by Venus to slow its frantic pace a bit, beginning a series of 24 close approaches to gather data. The probe's final approach will be in 2025, and it will journey less than 4 million miles (6.5 million kilometers) from the star, within the corona's outer edge — and the intricacies of what it's able to record are anybody's guess.

"I suspect it's going to be complicated; I suspect some of us will argue with each other as to exactly what's going on," Parker said. "But you've got data to work with, and you have a chance of getting it straightened out."

Editor's note: NASA's Parker Solar Probe will launch Saturday, Aug. 11, at 3:33 a.m. EDT (0733 GMT). You can watch the launch live here on Space.com beginning at 3 a.m. EDT (0700 GMT), courtesy of NASA TV. Visit Space.com Saturday for complete coverage of NASA's Parker Solar Probe launch.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.