How Realistic Is the Science in the CBS Show 'Salvation'?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The new CBS show "Salvation," which premiered last Wednesday (July 12), explores a fictional scenario in which scientists and the U.S. government must respond to the threat of a deadly asteroid expected to hit Earth in six months.

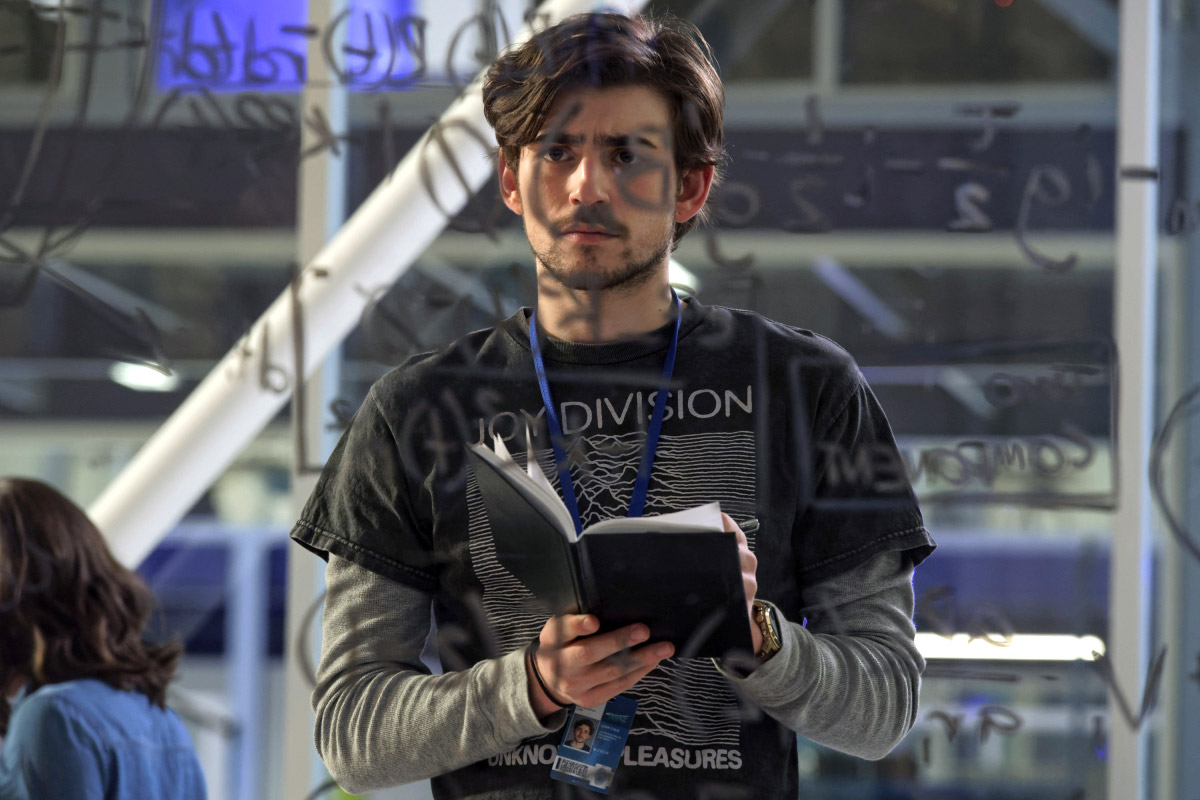

The first episode (fear not; we're making this spoiler-free) introduces a hotshot astronomical genius student, his experienced but more cautious professor and a billionaire space entrepreneur working on really cool futuristic technology. There's much talk about asteroids, gravitational interactions and holographs.

But how much of the science is accurate? Space.com talked with Phil Plait, who writes the popular space blog "Bad Astronomy" and is a science adviser for the show. [Here's How an Asteroid Threatens Earth in CBS' 'Salvation' (Gallery)]

"The first thing to make clear is, this is a TV show — it's not a documentary," said Plait. After all, the season has only a few episodes, so sometimes, the "science is going to bend to the story," he added.

"There are never any fictional portrayals that are going to make 100 percent sense," he told Space.com. Even in "the best movies," such as "2001: A Space Odyssey" and "Contact," he said, there are "twisted" or extrapolated elements, or just plain mistakes. "It's going to happen," Plait said.

But Plait praised the show's writers for their efforts to get things right. Particularly in the early days of the production, Plait would receive frequent phone calls where he would discuss asteroids, methods for finding them and other science topics related to the show.

The asteroid

The asteroid in "Salvation" is portrayed as a menace that would wipe out all life on Earth. The size of the asteroid is not disclosed in the early episodes, but Plait said it's fair to assume that the object is very large — big enough that, in the real world, it would most likely be picked up by telescopes years ahead of arrival. (And in the real world, scientists aren't aware of any space object posing an imminent danger to Earth.)

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A few years ago, NASA announced that it had found 90 percent of asteroids that are at least 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) in diameter — large enough to cause immense regional destruction, at the least. For comparison, the asteroid that likely killed the nonavian dinosaurs about 65 million years ago was probably about 10 times that size.

NASA is now on a Congress-mandated search to find 90 percent of asteroids that are at least 460 feet (140 meters) across. The initial deadline was 2020, but NASA has said that a lack of sufficient funding will prevent the agency and its network partners from reaching that goal on time.

In "Salvation," the asteroid's threat appears to have been found by only a few academics running simulations, although it's not 100 percent clear so far. The reality is less glamorous, Plait said.

"When you're building drama, if you stick to reality and say we've discovered an asteroid through an automatic [asteroid] survey that has a 1-in-15 chance of impacting the Earth in 22 years, that's not going to drive your storyline really well," Plait said.

"They accelerate that storyline quite a bit, [to] six months," he continued. "Is that possible? It's certainly possible to have an impact with that little warning," Plait said, pointing to the example of the 20-meter (65 feet) body that broke up above Chelyabinsk, Russia, in February 2013. The show accurately portrays that Chelyabinsk happened with no warning and caused hundreds of injuries.

The scientists and engineers

So far, viewers of "Salvation" have been introduced to a few key scientists and engineers in both the university and the private sector. An initial 45-minute episode makes it tough to tell ahead of time how stereotypical their portrayals will be, as we are just getting to know them. That said, Plait pointed out that representation of science is also an important part of television and film.

"It's an interesting, very complicated relationship, because you basically see two or three scientists in the show, so you're not going to get a huge statistical representation of what scientists are like," Plait said.

As a graduate student, Plait said, his fellow scientists were a diverse bunch; there was a vegetarian, a computer science professional, a ski instructor, a skydiver. But Plait also ran into more nerdy types of people that were very similar to the famous neurotic characters on "The Big Bang Theory."

"All of these different types of people go into science," Plait said. "When you talk about what scientists are like on TV, sometimes you see that diversity and sometimes you don't."

Plait said he used to be the kind of person who enjoyed nitpicking the science of TV shows, but now he is more interested in how consistent a science explanation is within the show's "universe". The concept is often used to evaluate the science used in to "Star Trek," he added.

An example for Trekkies is why the Klingons — one of the alien races — had no bumps in their faces in the show's original series (1966-1969), but those bumps began appearing in later iterations of the show. The real answer was makeup techniques, Plait said, but in the show's storyline, the bumps were linked to a virus.

So viewers of "Salvation" should give the show some leeway with the science accuracy and instead focus more on how the science drives the plot, Plait said.

"As far as I'm concerned, it's fine as long as there's an internal consistency and the story is told well and the science isn't egregiously disturbing," he said.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.