Planet Hunters Edge Closer to Their Holy Grail

The announcement that a small Earth-like planet has been found within the habitable zone of a distant star is the result of more than a decade-long search for worlds like our own.

The first planets outside our solar system were spotted in 1990 and were in some sense a disappointment. They were dead worlds, in orbit around a spinning stellar corpse that bathed them with deadly radiation. The first planet circling a normal star outside our solar system was not discovered until 1995. This enormous gas giant called Peg 51 b hugged its star tighter than Mercury does our Sun, so it hardly resembled Earth or afforded conditions friendly to life.

Fast forward 12 years and the number of extrasolar planets, or "exoplanets," has swelled to nearly 230. The latest discovery shows planet-hunting scientists are closing in on the Holy Grail of their field: finding another world like our own.

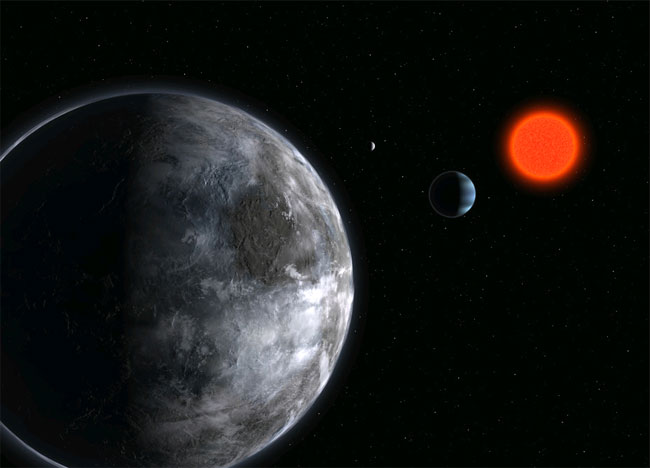

The new world, called Gliese 581 C, is only about five times the mass of Earth. It lies within the habitable zone of its tiny red parent star and can thus sustain liquid water on its surface, and with it, possibly life.

A dizzying variety

Gliese 581 C is only the latest (and smallest) in a dizzying variety of alien worlds known so far. There are now known exoplanets that orbit normal stars, giant stars, dwarf stars, dead stars, double stars, and even triple stars. Some orbit no stars at all, floating freely through space.

There are water worlds, blistering gas giants, and even potentially rocky planets like our own. One has even been photographed.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

There are young planets possibly less than one million years old and ancient worlds nearly 13 billion years old. There are close worlds only 10.5 light years away and remote ones an incredibly far 28,000 light-years distant.

Planet hunting techniques

The scores of newly identified exoplanets are the result of the numerous techniques now available to planet-hunting scientists. Peg 51 b was discovered using the radial velocity technique whereby astronomers look for slight wiggles in a star's motion caused by the gravitational tug of orbiting planets. This so-called wobble technique was also used to spot Gliese 581 C.

The transit method, another tool used by planet hunters, requires that a planet pass directly in front of its star as seen from Earth. The planet blocks some of the star's light that would reach Earth, and this slight dip in starlight can be used to calculate the planet's size.

Scientists can also spot alien worlds by observing the way a planet-harboring foreground star bends and brightens light from a background star. This technique is called gravitational microlensing. The presence of an extrasolar planet can also be inferred from the dusty debris disks that shroud some stars.

Raising the stakes

Stakes in the search for extrasolar planets have risen even higher with the recent launch of the European Space Agency's planet-hunting spacecraft, COROT, which will use the transit technique to monitor thousands of stars simultaneously. Over the course of its two-and-a-half year mission, it is expected to find up to 40 new rocky worlds, along with tens of new gas giants.

The NASA Kepler mission, scheduled to launch next year, is even more ambitious. The spacecraft would be the first capable of detecting Earth-sized planets in our galaxy. NASA's Terrestrial Planet Finder mission is currently on the backburner indefinitely, but it would have the same capability as Kepler. If launched, the satellites will mark an important step in the quest to answer one of humanity's oldest questions: Are we alone in the universe?

That's if Earth-bound astronomers don't make the discovery first. The discovery of Gliese 581 C showed the radial velocity technique could spot planets much smaller than scientists had predicted only a few years ago.

"I don't think there is a hard limit," said David Charbonneau, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. "Several years ago, everyone said there was a limit of a few meters per second. Now clearly their measurement precision is many times better than that. So I'm optimistic we can keep pushing."

Stephane Udry, an astronomer at the Geneva Observatory in Switzerland and the leader of the Gliese 581 discovery team said: "I am completely convinced we will find more [small exoplanets] soon, and around Sun-like stars."

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.