Mercury Is Joining 2017's Evening Sky: How to See It

Venus will leave the evening sky this week as it passes through inferior conjunction on March 25 and transitions into a morning object. But as Venus departs the evening sky, another planet will soon take its place: Mercury, the planet closest to the sun.

Beginning now and running into the first week of April, Mercury — a somewhat overgrown version of our moon — will have an evening appearance about as favorable as Northern Hemisphere denizens ever get to see.

In general, the most favorable elongations of Mercury — occurring in morning or evening — are those when the planet rises or sets in a dark sky, and that situation will occur for more than a week beginning later this month. From March 27 through April 5, Mercury will set at (or shortly after) the end of evening twilight, which will occur more than 90 minutes after sunset for mid-northern latitudes. [These Are the Brightest Planets in the March Night Sky]

Mercury is popularly known as the "elusive" planet, but despite its reputation, the planet is actually not very difficult to spot; just find a reasonably unobstructed horizon. A clear, haze-free sky also helps.

There is an oft-told story that Nicolaus Copernicus, the man who pushed hard for placing the sun — and not the Earth — at the center of our solar system, never saw Mercury. Although the climate of his homeland (Poland) tended to be rather cloudy and misty, one would have to believe that such a noteworthy figure in the field of astronomical calculation must have surely tried to spot Mercury when the weather was more favorable. Indeed, Mercury was far from impossible to glimpse during elongations as favorable as the upcoming one.

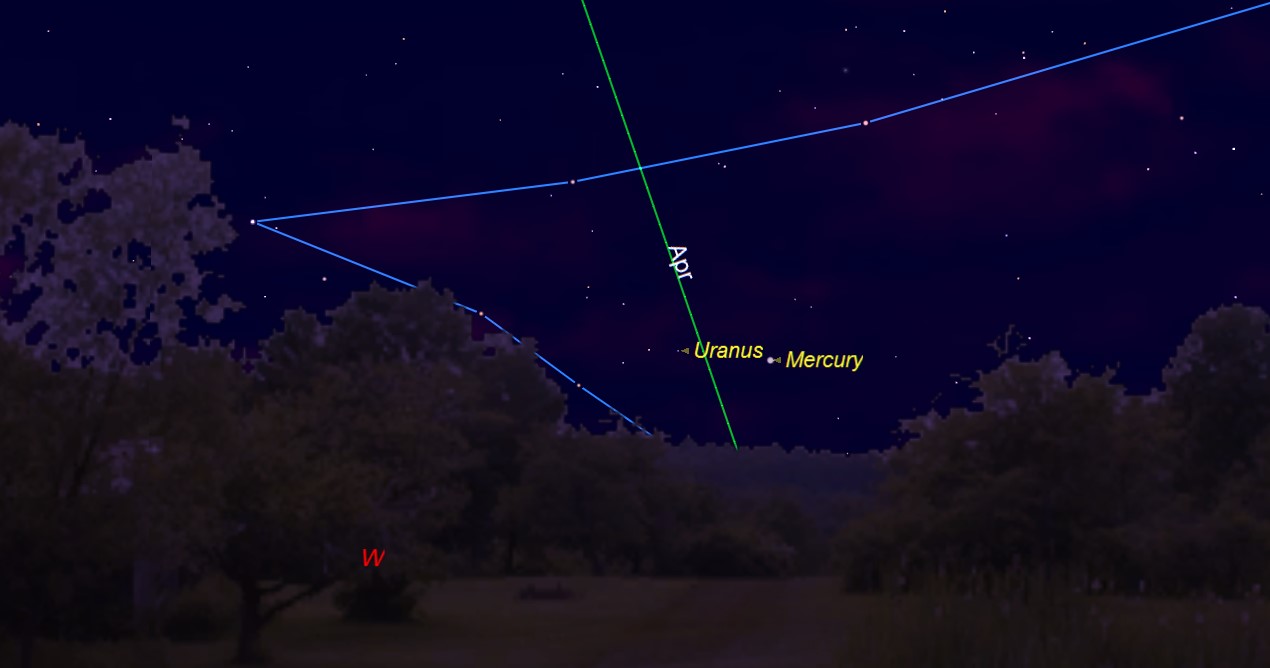

Currently, Mercury sets about 45 minutes after sunset. About a half-hour after sundown, look for it very near to the horizon, a bit to the north of due west. Weather permitting, you should have no trouble seeing it as a very bright "star" shining with just a trace of a yellowish-orange tinge.

Mercury is currently shining at a very bright magnitude of minus 1.4 on the brightness scale used by astronomers. In fact, among the stars and planets, Mercury now ranks behind Venus and Jupiter, and is tied for third with Sirius (the brightest star).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Mercury's time to shine

In the evenings over the next few weeks, Mercury will diminish in brightness — slowly, at first — but it will also be arriving at its greatest elongation, 19 degrees to the east of the sun, on April 1. (Your closed fist held out at arm's length covers 10 degrees of the night sky.) Shining then at a magnitude of minus 0.2 (just a trifle brighter than the similarly hued star Arcturus), Mercury should be readily visible, appearing low in the western sky and setting more than 90 minutes after the sun.

Mercury, like Venus and Earth's moon, appears to go through phases. Right now, it resembles a gibbous phase, which is why it currently appears as bright as Sirius. By the time it arrives at its greatest elongation, it will appear roughly half-illuminated, and the amount of its surface illuminated by the sun will continue to decrease in the days thereafter. So when it begins to turn back toward the sun's vicinity after April 1, it will fade at a rather rapid pace.

In fact, on the evening of April 8, Mercury's brightness will have dropped to magnitude 1.6 — as bright as the star Castor, in Gemini, and only one-sixth as bright as the planet appears now. In telescopes, it will appear as a narrowing crescent phase. In all likelihood, this will be your last view of it, for the combination of its rapid fading and its descent into the brighter sunset glow will finally render Mercury invisible by the second week of April.

Mercury in legend

In ancient Roman legends, Mercury was the swift-footed messenger of the gods. The planet is well-named because it's the closest planet to the sun and the swiftest of the sun's family of eight planets, averaging about 30 miles per second (48 kilometers per second) and completing one circuit of the sun in only 88 Earth days.

Interestingly, it takes Mercury 59 Earth days to rotate once on its axis, so all parts of its surface experience periods of intense heat and extreme cold. Although its mean distance from the sun is only 36 million miles (58 million km), Mercury experiences by far the greatest range of temperatures: nearly 900 degrees Fahrenheit (482 degrees Celsius) on its dayside and minus 300 degrees F (minus 149 degrees C) on its nightside. [Space Quiz: So You Think You Know Mercury?]

In the pre-Christian era, Mercury actually had two names, as people at the time did not realize that the planet could alternately appear on one side of the sun and then on the other. The planet was called Mercury when it was in the evening sky, but it was known as Apollo when it appeared in the morning. It is said that Pythagoras, in about the fifth century B.C., pointed out that they were the same.

One final note: About 45 minutes after sunset on March 29 , look low toward the west, and you'll see a slender waxing-crescent moon sinking toward the horizon. And situated well off to its right, you'll see Mercury — a great occasion to make a positive identification of the so-called elusive planet using our nearest neighbor in space as a benchmark.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Fios1 News in Rye Brook, New York.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.