Look Out Below! Landslides Spotted on Pluto's Moon Charon

Look out below! Scientists have found evidence of landslides on Pluto's moon Charon. This is the first time this geologic feature has been discovered in the Kuiper Belt, according to New Horizons scientists.

The landslides on Charon were spotted by NASA's New Horizons probe, which made a close flyby of the Pluto system in July 2015. According to New Horizons scientists, this is the first evidence of landslides in the Kuiper Belt, the region of icy, rocky bodies that lies beyond Neptune's orbit and includes the Pluto system.

It's unclear what caused the landslides, but possibilities include tectonic activity below the surface, or meteorite impacts, according to Ross Beyer, a New Horizons team member and researcher at the SETI Institute. Beyer discussed the finding at a news conference at the American Astronomical Society's Division of Planetary Sciences 2016 meeting in Pasadena, California. [Photos of Pluto and Its Moons]

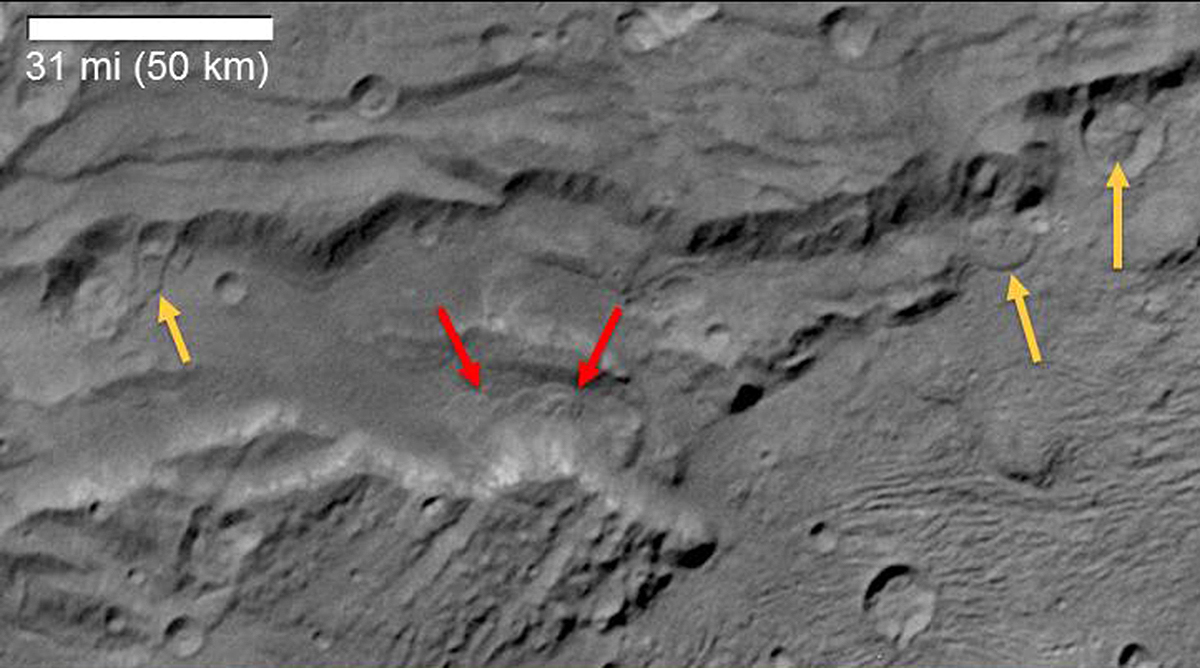

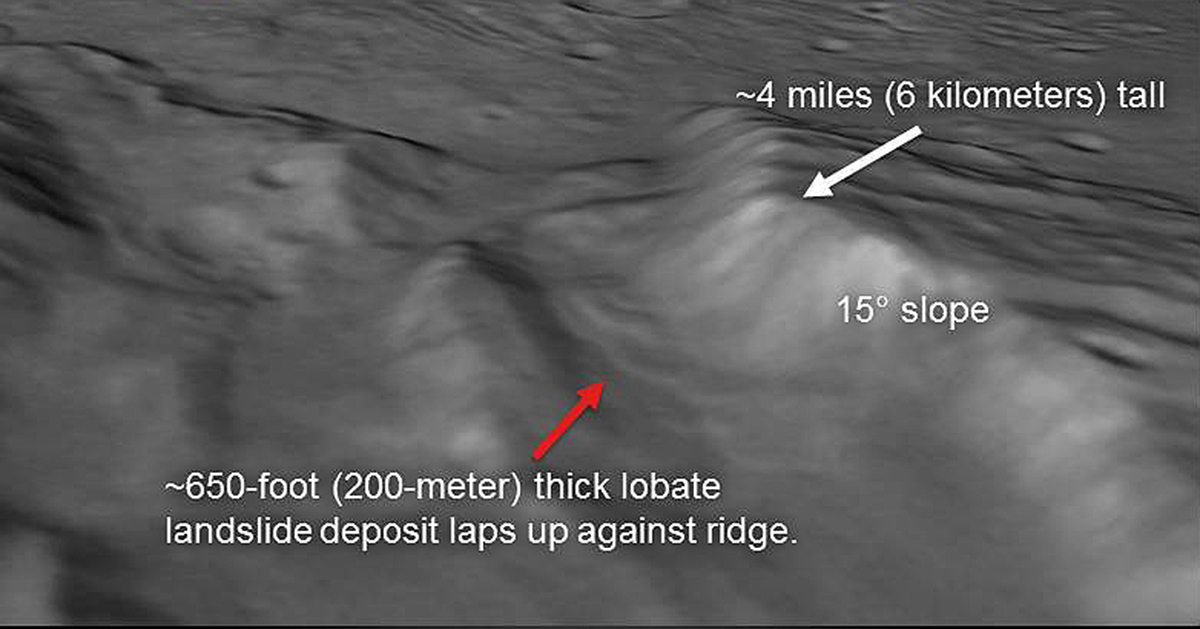

Four landslides were spotted on Charon in total, all in Serenity Chasma, which is part of a vast belt of deep canyons bordered by cliffs stretching for 1,100 miles (1,800 km) and reaching heights of up to 4.5 miles (7.2 km), according to NASA. In those areas, the scientists can see that material has dropped vertically down the cliffs and then moved horizontally into the canyon.

For a geologic event to be considered a landslide, it must involve a large amount of material that moves very quickly, and moves vertically (falls downward) as well as horizontally, Beyer said.

Based on the available data, Beyer said scientists have a lot of open questions about the landslides, including how and when they formed. The presence of landslides doesn't provide any new information about the chemical composition of the surface of Charon, but it does reveal something about the strength of that material.

"One of the requirements for a landslide is, you have a steepened slope that can then fail," Beyer said, adding that not all materials are strong enough to create such a slope. "On Charon, we think that [the material] is a strong, cold water ice that makes up all of the surface that we primarily see there."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Beyer said the images from Charon do not have a high enough resolution for the research team to see what the material in these landslides looks like, or whether the water ice is broken up into very large chunks or smaller granules. With better resolution, it might also be possible to look for meteor impact craters on the surface of the landslides, which would help scientists figure out when the landslide took place.

Landslides have been spotted on other icy bodies in the solar system, like on Saturn's moon Iapetus. But Beyer said this is the first time they have been discovered in the Kuiper Belt, which is the region of icy, rocky bodies that lies beyond the orbit of Neptune and includes the Pluto system.

On Pluto, scientists have seen ice flows moving slowly across the heart-shaped plain known as Sputnik Planitia (previously known as Sputnik Planum) and small amounts of material that appear to have tumbled down cliffs. But so far, there is no evidence of landslides there.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter