Red Planet Triumphs and Defeats: A History of Mars Missions

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Missions to Mars have never been easy.

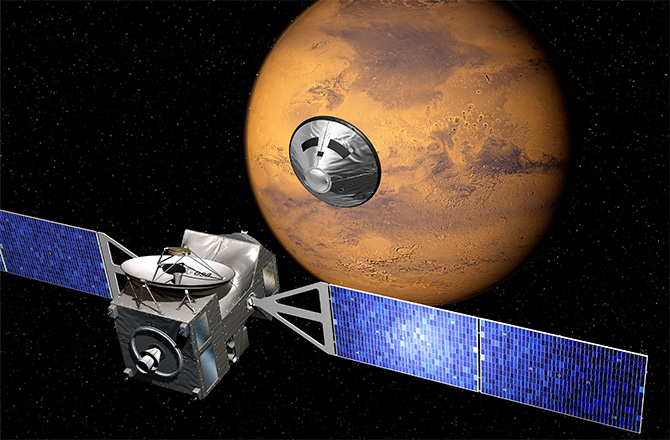

On March 14, Europe and Russia are scheduled to launch the first phase of the two-part ExoMars program toward the Red Planet. The spacecraft will carry an orbiter and a soft lander; the second phase, scheduled to launch in 2018, will send a rover to the Martian surface.

The upcoming ExoMars launch comes just a few years after the failed Russian-Chinese Fobos-Grunt mission, which lifted off in November 2011 but never made it beyond Earth orbit. Since 1960, more than half of all attempted Mars missions have failed. But humanity's exploration of Mars has also had some amazing successes. Here's a look back at the history of robotic missions to the Red Planet. [Journey to the Red Planet: A Mars Missions Time Line]

In the beginning

In 1960, the Soviet Union became the first country to attempt to send a probe to Mars. The then-unnamed probe (it has seen been referred to as Marsnik 1, Mars 1960A and Korabi 4) failed to leave Earth orbit. The Soviet Union suffered a string of 10 failed Mars missions until finally, in 1971, the Mars 3 orbiter reached its destination. This probe studied Mars for eight months before landing on the planet's surface, where it was able to collect 20 seconds of data before shutting off permanently.

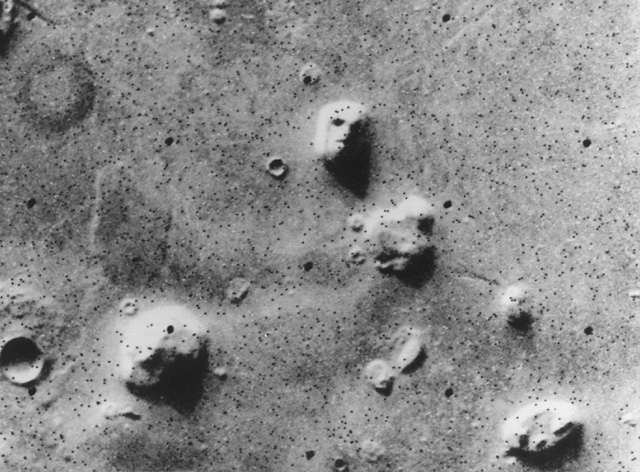

The United States' first attempted Mars mission was Mariner 3, which launched in 1964. The probe's solar panels failed to open, so it could not take up orbit around Mars. But, Mariner 4, also launched in 1964, succeeded in its mission, becoming the first human-made probe to study the Red Planet up close. During Mariner 4's brief flyby, the probe sent back 22 images and came to within 6,118 miles (9,845 kilometers) of the Martian surface.

In 1969, the United States launched two more successful Mars flyby missions: Mariner 6 and 7. In 1971, Mariner 8 was lost in a launch failure, but in November of that year, Mariner 9 became the first artificial satellite to orbit a planet other than Earth. It returned more than 7,300 images of Mars.

New ambitions

Beginning in 1973, the Soviet Union experienced a period of limited successes with its Mars program. The Mars 4 probe reached Mars but failed to go into orbit, although it did return some images and data. Mars 5 successfully entered into orbit around the Red Planet in February 1974. In March of that year, the Mars 6 orbiter/soft lander reached Mars, but the lander failed on its descent. The lander did manage to return some data from the Martian atmosphere, however.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Mars 7 spacecraft failed to go into orbit around Mars as planned in 1974, and while the mission's lander was released, it missed the planet. According to NASA's history office, Mars 7 and four of the U.S. Mariner probes are now orbiting the sun.

In 1975, the United States launched its Viking 1 and Viking 2 orbiter/lander Mars missions. Both Viking 1 and Viking 2 touched down on the planet's surface in 1976. With the exception of the 20 seconds of data received from Mars 3, the Viking landers provided the first on-the-ground data from Mars. Together the two probes went on to collect over 52,000 images.

In 1988, the Soviet Union launched the Phobos 1 orbiter and the Phobos 2 orbiter/lander to study Mars' larger moon, Phobos. But controllers lost contact with Phobos 1 before the probe reached its destination. Phobos 2 entered into orbit around Mars but failed before it could drop its lander on the nearby moon.

After launching the failed Phobos probes, the nation's Mars missions became much more infrequent. In 1996, Russia (the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991) mounted the Mars 96 mission, which consisted of an orbiter, two landers and two soil probes. But the mission was lost in a launch failure.

In the 1990s, the United States experienced two Mars mission successes and a total of four mission failures (this latter tally includes the Mars Polar Lander and the two Deep Space 2 impact probes, which were considered separate missions, even though they were launched together). Among the country's successes was Mars Pathfinder, the first rover on Mars. It landed on the Red Planet on July 4, 1997, and worked for five years longer than expected.

In 1998, Japan attempted to launch a Mars mission. The Nozomi probe would have been the country's first probe to reach another planet. Nozomi was scheduled to reach Mars in December 2003, but contact was lost before then. [The Boldest Mars Missions in History]

The new century

Since 2001, the United States has had a stunning run of seven straight successful Mars missions, including three rovers.

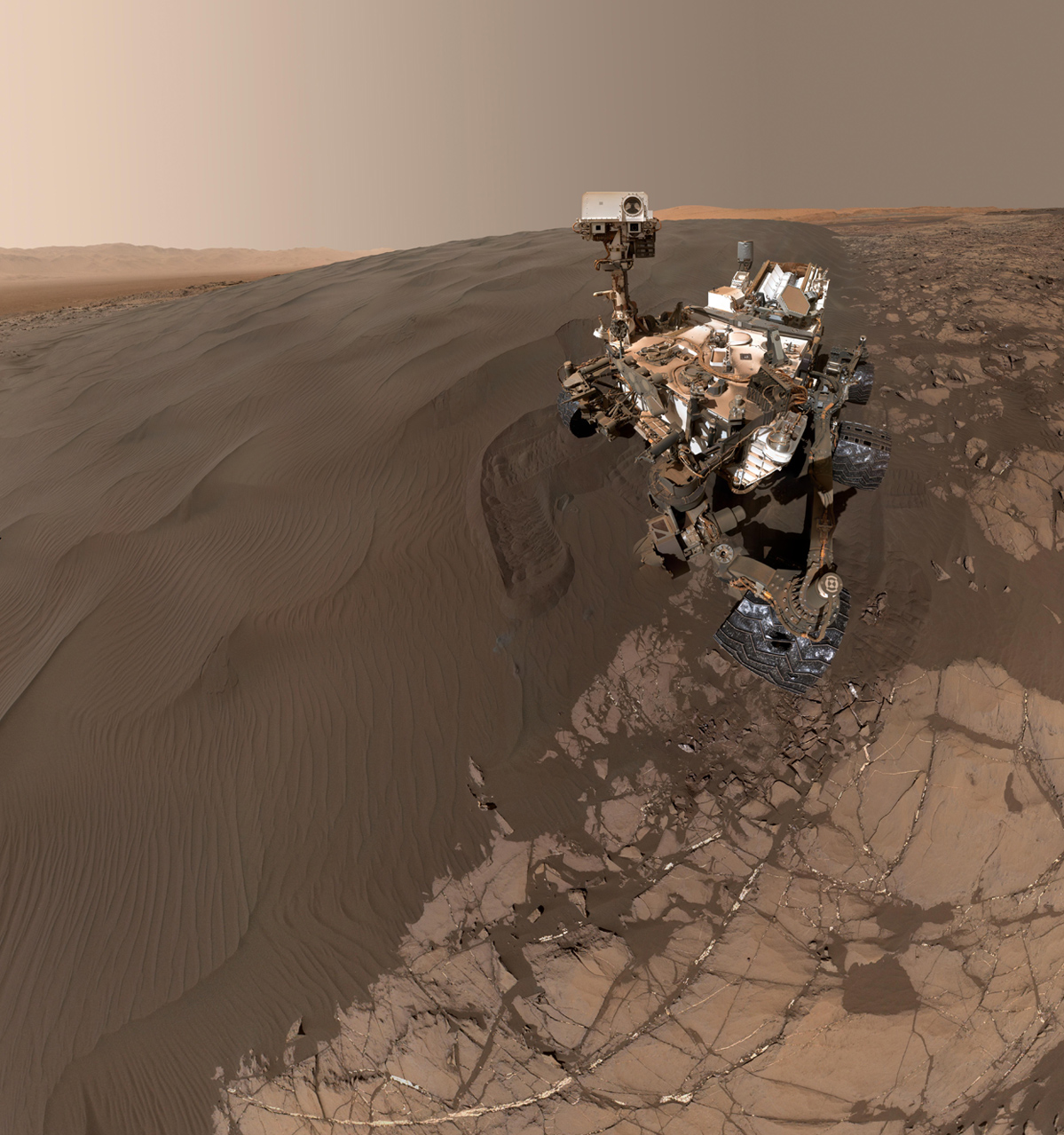

NASA's Mars Curiosity rover, which landed in August 2012, continues to provide on-the-ground information about the Red Planet, and the agency's most recent Mars probe, MAVEN (Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution), has helped scientists explain what happened to Mars' ancient atmosphere. Meanwhile, the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), launched in 2005, has helped scientists identify locations where liquid water appears to exist on the Martian surface.

In 2003, the European Space Agency (ESA) experienced a partial success with the Mars Express mission, which included the Mars Express Orbiter and the Beagle 2 lander. ESA lost contact with Beagle 2, but Mars Express is still orbiting the Red Planet, more than a decade after arriving.

India joined the Mars race recently with the Mars Orbiter Mission, also known as Mangalyaan. The probe reached Mars in September 2014 — the same month as MAVEN — and continues to operate beyond its initial mission time frame.

In 2011, Russia and China launched a joint Mars mission called Fobos-Grunt. Due to a malfunction, the spacecraft got stuck in Earth orbit, eventually falling back to Earth.

But the March 14 ExoMars launch gives Russia another chance at the Red Planet. ESA leads the ExoMars program and is building most of the hardware; Russia is providing the Proton rockets for both launches, as well as some flight gear and science instruments.

The first phase of ExoMars consists of an orbiter that will hunt for methane — a possible sign of Mars life — in the planet's atmosphere and a landing demonstrator, which test landing technologies for the program's rover, which is scheduled to launch in 2018.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter

![Since the 1960s, humans have invaded our neighboring planet Mars with swarms of spacecraft. Only about half of the attempts have been successful. See how many robot missions to Mars have launched in this SPACE.com infographic. [See the Full Occupy Mars Infographic]](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/axtSHqkGu8QzSEiswjhZ6d.jpg)