Mariner 4: First Spacecraft to Mars

Mariner 4 was the first spacecraft to fly by Mars, and the first to return close-up images of the Red Planet.

Its blurry views of craters and bare ground led some scientists to think that Mars is similar to the moon. It squashed some views that Mars was a haven for life.

Nevertheless, NASA continued to send spacecraft to Mars because Mariner 4 only took pictures of part of the surface. Later missions showed that Mars is actually quite different from the moon, with an active weather system and a much wetter past.

Mars before Mariner 4

It's hard to pinpoint when the discussions of life on Mars began in earnest, but two astronomers' observations of the Red Planet in the late 1800s and early 1900s helped spur a wave of interest.

Percival Lowell, an American businessman (and other things besides), spent years studying Mars from an observatory he financed at Flagstaff, Ariz. He made sketches of the surface and published the results. Telescope resolution wasn't all that great at the time, but Lowell felt that he was seeing canals on the Red Planet that were possibly built by intelligent beings.

As his observations became public, interest in Mars was soaring. Dozens of books, movies and television programs portrayed different views of civilization, ranging from H.G. Wells' "War of the Words" to Martian aliens in episodes of "The Twilight Zone" to Marvin the Martian on "Looney Tunes."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Getting to Mars

NASA had its own reasons for going to the Red Planet. The nascent field of exobiology was examining the possibilities of life on other worlds. (And just as vehemently, scientists began invoking their concerns about hurting or disturbing that life through human exploration.)

But scientists could only see so much detail through a telescope. A close-up view would be required to see what the Martian environment was like, before drawing conclusions. NASA originally wanted to have a lander on the planet, but scaled that back in 1962 when planners determined a Centaur rocket stage would not be ready for the planned 1964 mission.

This was the early days of space exploration, with a high rate of failure as NASA and the Soviet Union each tested new technology. As such, NASA elected to send two spacecraft to Mars around the same time – Mariner 3 and Mariner 4. This success had worked previously with Mariner 1 and Mariner 2's voyages to Venus; while Mariner 1 failed, Mariner 2 successfully sent back information.

Mariner 3 launched Nov. 5, 1964. It made it into space successfully, but a fairing intended to protect the spacecraft during launch jammed instead of coming off as planned. This doomed the spacecraft before the mission could get started.

This left only Mariner 4 to carry out the mission. NASA and its contractors hastily redesigned the nose fairing in the three weeks before its launch, and cheered its success when the spacecraft successfully headed for Mars on Nov. 28. The 574-pound (260 kilogram) spacecraft spent more than seven months cruising to the Red Planet.

A close encounter

Mariner 4 spent just 25 minutes doing observations of Mars as it cruised by on July 14, 1965. In that brief time, it took 21 full pictures that it beamed back to Earth the next day. The spacecraft's views would be the first ones beamed back from another planet.

From 6,200 miles to 10,500 miles (10,000 to 17,000 kilometers) up, Mariner 4 was too far away to see life such as plants or animals, NASA cautioned. Still, it would perhaps be close enough to figure out if there were canals or not.

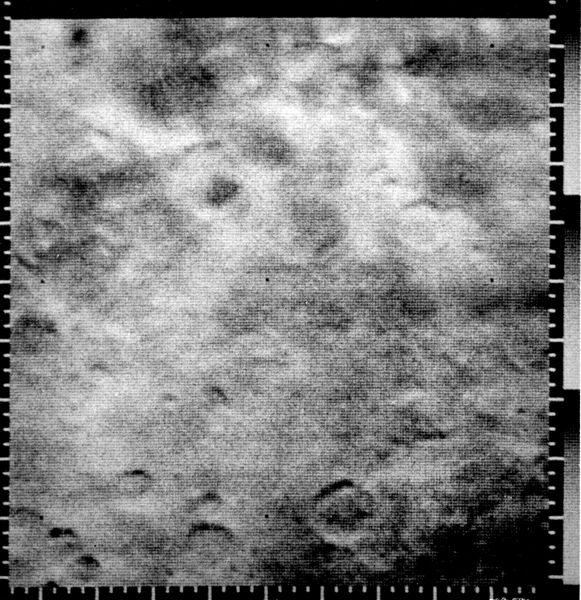

After the pictures came back, they showed no canals or any obvious signs of life at all. Although blurry by today's standards, the images were clear enough to reveal a heavily cratered surface. Scientists said it appeared Mars was more similar to the moon than to Earth.

"Man's first close-up look at Mars had revealed the scientifically startling fact that at least part of its surface is covered with large craters," NASA stated when it released the pictures.

"Although the existence of Martian craters is clearly demonstrated beyond question, their meaning and significance is, of course, a matter of interpretation.''

While no canals were visible, there was a diversity of craters. They ranged in size from about 3 to 75 miles (5 to 120 kilometers). Scientists supposed the craters must be two to five billion years old, similar to what is seen on Earth's moon. They also said the Mars atmosphere must be thin indeed to preserve the craters as well as they appear.

The brief glimpse of Mars revealed no mountains, valleys or similar Earth-like features. Of course, later missions to Mars revealed high-rising volcanoes and Valles Marineris, an immense chasm many times greater than the Grand Canyon.

Reaction to Mariner 4's results

According to NASA, the Mariner 4 mission forced most exobiologists to accept that life would not be obviously found on Mars. There was disappointment among some scientists, and the public alike. "The New York Times" remarked that Mars is "probably a dead planet."

However, there was a large degree of uncertainty because the mission had only imaged a part of the planet, and had spent less than half an hour doing its work there.

A new view began to emerge that life was still present on Mars, but perhaps lurking in "micro-environments" such as in a volcano, or in a spring on the Red Planet. This view appears closer to our understanding of proposed Martian life today.

NASA continued its exploration of Mars out of recognition that Mariner 4 only showed a partial view. Its next major mission there, Mariner 9, revealed a planet of varied environments.

With renewed interest, NASA sent two Viking landers to the surface in the 1970s and performed life experiments; the results are still under debate today.

NASA's continued exploration of the Red Planet has revealed a much less barren surface than what Mariner 4 suggested.

The Spirit, Opportunity and Curiosity rovers have all found evidence of past water on the surface, with their "ground truth" observations supplemented by large-scale views of the planet from orbiting spacecraft.

When it comes to finding life on Mars, we still don't have a definitive answer. Mariner 4's greatest lesson to science is teaching us not to jump to conclusions. It will take several points of evidence before we can definitively say there was something – or nothing – living on the Red Planet.

— Elizabeth Howell, SPACE.com Contributor

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.