European Space Agency's Mars Express

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

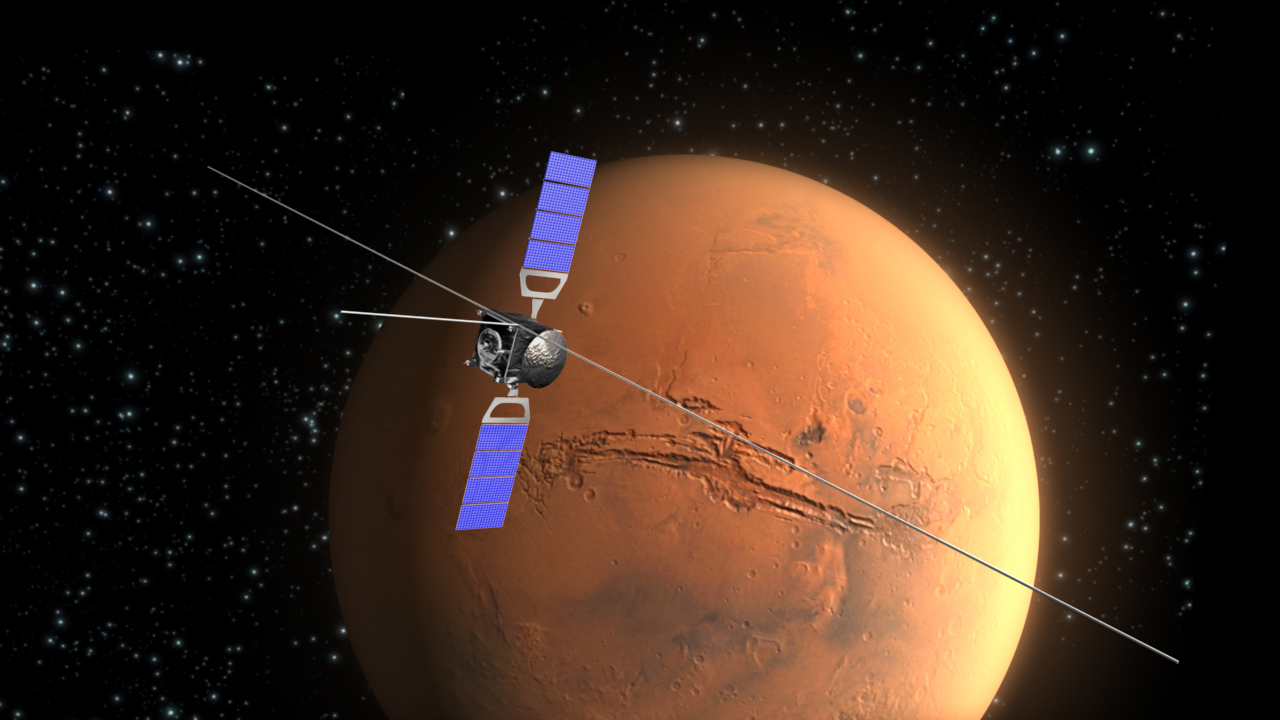

Mars Express is the European Space Agency's first spacecraft built to explore another planet. It arrived at Mars on Dec. 25, 2003, along with a lander called Beagle 2. The orbiter is still circling the Red Planet after nearly 15 years of operations there, but its lander Beagle 2 lost contact with Earth in December 2003 before it reached the surface.

Among other achievements, Mars Express found methane in the Martian atmosphere, mapped the composition of polar ice, found a possible subsurface water deposit under the south pole, and flew close to the Martian moon Phobos. The mission is budgeted to stay at Mars until at least the end of 2020, which will allow it to help the European ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (and possibly the ExoMars rover, which launches in 2020) through their first few years of observations.

Development and delivery

Some of the instruments on Mars Express were originally intended for a mission called Mars 96, which failed shortly after launch on Nov. 16, 1996. Mars Express' high-resolution stereoscopic camera, and a mineralogical mapping spectrometer, both originated with Mars 96. ESA also borrowed several of Mars Express' science goals from Mars 96. The science goals include, in ESA's words:

- Global high-resolution photogeology (including topography, morphology, paleoclimatology, etc.) at 10 m (32 feet) resolution

- Super-resolution photogeology of selected areas of the planet (2 m or 6.5 feet/pixel)

- Global high spatial resolution mineralogical mapping of the Martian surface at kilometer scale down to several 100 m (330-feet) resolution

- Global atmospheric circulation characterization, and high-resolution mapping of the atmospheric composition

- Subsurface structure characterization at kilometer scale down to the permafrost

- Surface-atmosphere interaction; interaction of the atmosphere with the interplanetary medium

- Structure of the interior, atmosphere and environment via radio science measurements

- Surface geochemistry and exobiology

The instruments on Mars Express include two types of instruments — surface/subsurface instruments and atmosphere and plasma instruments. The surface/subsurface instruments are:

- HRSC (High Resolution Stereo Camera)

- OMEGA (Visible and Infrared Mineralogical Mapping Spectrometer)

- MARSIS (Sub-surface Sounding Radar Altimeter)

The atmosphere and plasma instruments are: PFS (Planetary Fourier Spectrometer)

- SPICAM (Ultraviolet and Infrared Atmospheric Spectrometer)

- ASPERA (Energetic Neutral Atoms Analyser)

- MaRS (Mars Radio Science Experiment)

- Visual Monitoring Camera (VMC)

Mars Express got its name from its speedy development. The European Space Agency, seeking to reduce the size of the development team, gave primary responsibility to prime contractor Astrium. The company used commercial off-the-shelf technology to finish the spacecraft faster. The orbiter cost just $195 million (150 million Euros) in 1996 prices.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Beagle 2 was a lander mainly developed by universities and companies in the United Kingdom, costing between $65 million and $80 million (40 to 50 million British pounds.) It was named after the HMS Beagle, a ship most famous for naturalist Charles Darwin's voyages in the 1830s. Darwin used his observations of nature on those trips as a basis for formulating his theory of natural selection.

Orbiter and lander launched successfully June 2, 2003, from Kazakhstan and arrived at Mars more than six months later, on Dec. 25, 2003.

Loss of Beagle 2

Beagle 2 was supposed to land on Mars in search of signs of ancient astrobiology, or extraterrestrial life. Although the lander would remain in place, it had a robotic arm that could scoop samples and take pictures from its perch on the surface.

However, ESA lost contact with the lander after its scheduled touchdown date on Dec. 25, 2003. Controllers kept trying to hail the spacecraft, but came up empty. The mission was declared lost in February 2004.

A government-private industry commission said that the spacecraft likely had a problem with its landing air bag, which either collided with the main parachute or released the lander at the wrong time. Also, the commission said inadequate management, risk evaluation and funding contributed to the failure.

In January 2015, NASA's high-resolution Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter found the Beagle 2 lander, its rear cover and possible signs of a parachute on the Martian surface. It was about 3 miles (5 kilometers) from the center of its landing zone in Isidis Planitia.

The evidence demonstrated that Beagle 2 did make it to the surface, but didn't unfold itself correctly, according to the UK Space Agency.

Early days at Mars

While Beagle 2 never began its mission, Mars Express carried on. The spacecraft made its first major discovery while its orbit was still being finalized. On Jan. 23, 2004, Mars Express spotted water ice and carbon dioxide ice at the Martian south pole. This meant the spacecraft already met its objective of finding water on Mars less than a month after reaching its destination.

Mars Express' team confirmed the water find in March 2004, saying the south polar cap is made up of 85 percent carbon dioxide ice and 15 percent at its center.

Weeks later, investigators came up with a second major discovery: finding methane on Mars. This excited scientists because methane is not expected to last long in the atmosphere.

This means there had to be some fuel for the methane on the planet's surface. Scientists theorized it might come from volcanoes, but said the matter required further study. There have been varying amounts of methane measured in Mars' atmosphere since then, including by the NASA Curiosity rover that arrived on the surface in 2012.

Mars Express experienced a major hiccup with MARSIS, a radar instrument that was supposed to be deployed in April 2004. Last-minute simulations indicated there could be a "whiplash" effect on the spacecraft if the deployment was not done with care, so controllers waited until more tests could be performed.

ESA moved ahead with the deployment in May 2005, encountering one snag as part of an antenna did not lock as planned. MARSIS became operational that June.

Mars in HD

One of the strengths of Mars Express is the higher resolution of its instruments. Camera pictures provided one of the best views of the Martian surface to date, allowing scientists to revisit the same areas and get more information. [Photos: Red Planet Views from Europe's Mars Express]

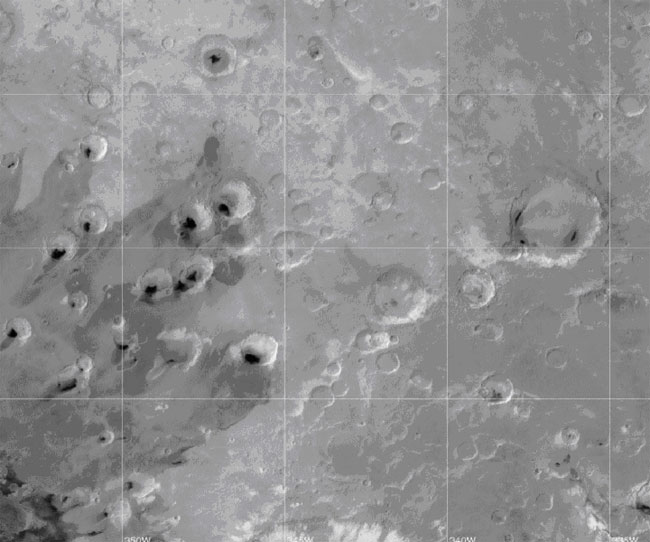

One famous example is the well-known "Face on Mars." First snapped by Viking 1 on July 25, 1976, the jumble of rocks and shadow on the Cydonia region appeared to form a human-like head. Conspiracy theorists and many people around the world became excited about the find despite NASA's cautions that the rocks only appeared as a face, and were not actually a face.

In 1998, NASA took another picture of the "face" using the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, revealing the face was a trick of shadow and poor resolution. Mars Express targeted the same area in 2001 and confirmed MRO's findings.

Mars Express' high definition camera also came in handy when scouting out the landing site for the Mars Curiosity mission. Its resolution of 330 feet (100 meters) per pixel helped planners reduce the planned landing site of the spacecraft, and helped narrow the landing zone.

Curiosity dropped to Mars just 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from the center of this target when it landed Aug. 6, 2012.

Mapping the interior

Mars Express' capabilities aren't just limited to surface features. MARSIS, which is now working fine, can map the interior of Mars as well as anything that happens to scoot nearby.

The spacecraft periodically flies near Phobos, one of the two tiny moons of Mars. In 2013, it passed only 45 kilometers (27 miles) above the surface to learn more about the inner structure of Phobos, which may be mostly empty space.

The lumpy moon is just 14 miles (22 km) in diameter. Some scientists, basing their findings on Mars Express data, believe the moon was formed after a comet or meteorite hit the planet in the ancient past. More observations were planned using the Russian Phobos-Grunt mission, but that spacecraft failed shortly after launch in November 2011.

In 2012, Mars Express spotted a possible ancient ocean on Mars: sediments on the planet's northern plains appeared to resemble what is seen on an ocean on Earth. The information came from more than two years of MARSIS data and buttressed previous observations showing possible Martian shorelines in the area.

A decade at Mars, and well beyond

To celebrate Mars Express' 10th anniversary at Mars in 2013, the team released several global maps showing where minerals have been formed by water and where minerals have been distributed by volcanic activity. The maps also pinpointed areas that could be worthy of future landing missions, such as cliff flanks that may be laden with ice deposits.

Comet Siding Spring whizzed by Mars in October 2014 at a distance of only 137,000 km (85,000 miles). Several Mars spacecraft in the vicinity (including Mars Express) performed observations of the comet. Mars Express' HRSC (High Resolution Stereo Camera) took several images, and the spacecraft's spectrometer also examined the comet. Scientists with ESA said they planned to use the data to learn more about the comet's composition.

A surprise find in September 2016, supported by data from Mars Express (along with other orbiters) suggested that some of the streams and lakes on Mars were only formed 2 billion or 3 billion years ago. Researchers were taken aback because the Red Planet likely had lost most of its atmosphere by then.

In October 2017, high-altitude cloud images captured by Mars Express (along with models and other data sets) were said to reveal details about how the atmosphere and seasonality change cloud features. Data from Mars Express also played a role in a stunning mosaic of the north pole released in February of that year.

In July 2018, scientists announced that MARSIS radar observations from Mars Express (collected over several years) may show a signature of water below the south pole of Mars; not all scientists agreed with the interpretation, but the study team said at the time that it was fairly confident in the result. "MARSIS was able to detect echoes from beneath the southern polar cap of Mars that were stronger than surface echoes. This condition on Earth happens only when you observe subglacial water like in Antarctica over places like Lake Vostok," said lead author Roberto Orosei, the co-investigator on MARSIS and a scientist at the National Institute for Astrophysics in Italy, in a video.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.