Mars Methane: Geology or Biology?

Plumes of methane gas detected over certain locations on Mars in 2003 could point to active geological processes on the red planet, or perhaps even to methane-burping microbes deep below the Martian surface, a new study reports.

There is no firm evidence for life on the red planet, however, despite news reports early today suggesting as much. Rather, scientists are puzzled by the new findings.

Methane, a small (but important) constituent of Earth's atmosphere, makes up an even smaller percentage of Mars' atmosphere (which is 95 percent carbon dioxide), so detecting it on the red planet is a rare event.

In fact, it wasn't detected at all before 2003, when the European Space Agency's Mars Express orbiter (which is still circling the planet) picked up a possible methane signature.

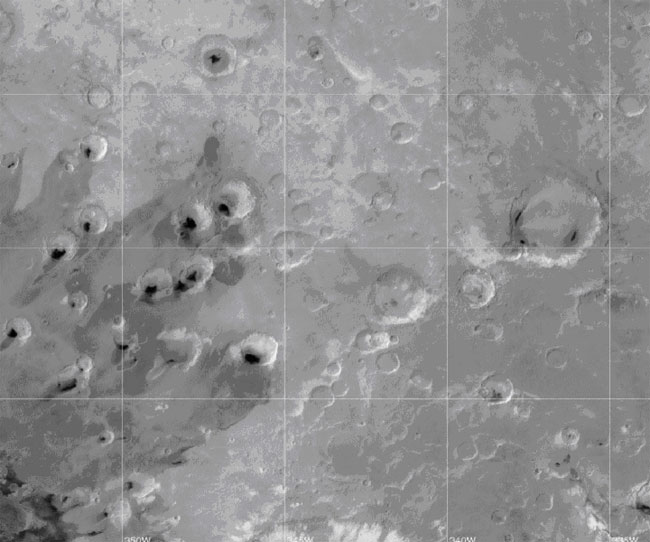

A search conducted with three ground-based telescopes that covered 90 percent of the Martian surface over three Mars years (7 Earth years) detected extended plumes of methane that varied with the seasons and seemed to emanate from specific locations. These include the Arabia Terra, Nili Fossae and Syrtis Major regions of Mars. The work was supported by NASA and the National Science Foundation.

In 2005, scientists also found signs of water ice beneath the surface near Mars' equator and, interestingly, near an area where methane has been detected.

The methane plumes started to show up in the northern hemisphere spring of Mars, gradually building up and peaking in late summer. At one point during the study, the primary plume contained about 19,000 metric tons (21,000 tons) of methane, comparable to the amount produced at the massive hydrocarbon seep at Coal Pit Point in Santa Barbara, Calif.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It's a heck of a signpost," said study author Michael Mumma of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

Where exactly the methane comes from is still unknown, though scientists have some ideas. Mumma and his team detailed these ideas and their findings in the Jan. 15 early online edition of the journal Science.

Geo or bio?

The release of methane is likely connected to the heating that happens as summer progresses in the northern hemisphere, Mumma said.

This heat could be melting ice that usually seals up pores or fissures in deep-relief areas such as scarps or craters walls (this is similar to how in the winter here on Earth, the sunny side of the street will have water and slush, while the shady side will stay frozen). The methane in this case would be coming from deeper below the surface.

Alternatively, the methane could be released by geochemical processes nearer the surface, within the top meter of the Martian terrain, Mumma said.

"We can't really tell the difference at this point," Mumma told SPACE.com.

On Earth, one of the main geological processes that releases methane is volcanism, but Mumma said this doesn't look to be the case on Mars because other gases spewed out in much greater amounts by volcanoes haven't been detected. Another possibility is a process called serpentization, which transforms iron oxide into a mineral known as serpentine.

The most tantalizing possibility though is that the methane comes from subsurface Martian microbes.

Possible Earth analogues are the communities of microorganisms that thrive in gold mines a few kilometers below the surface in the Witwatersrand Basin of South Africa. The microbes use molecular hydrogen (produced as radioactivity in the surrounding rocks breaks apart water molecules) as an energy source, turning carbon dioxide to methane. Because photosynthesis isn't required, this same process could be taking place below the cryosphere boundary deep below the surface of Mars, where water transitions from ice to liquid water.

Of course, Mumma cautions, "we cannot state that we have detected biology or refute it."

Meanwhile, Tullis Onstott of Princeton University and colleagues are working on a new device for a potential future rover mission that could trace the origin of the methane.

Short-lived

Outside of the plumes, methane concentrations were very low, showing that the gas didn't get very far or last very long in the atmosphere. In fact, its lifetime was even shorter than expected or could be explained by the usual method of methane destruction, photolysis (reaction with sunlight).

Instead, oxidation (the same process that rusts iron) could be destroying the methane. The Viking landers demonstrated that peroxides were found in the Martian dirt, and the Phoenix Mars lander found evidence for perchlorates, another oxidizer (whether they are found outside of the polar regions is not yet known).

Mumma and his colleagues suggest that peroxide-coated dust grains lofted into the air could be eating away at the methane.

The team is planning to do more observations of Mars from ground-based telescopes to see if they find more plumes, as well as whether the previously-observed ones come back again in the summer.

"The issue still is was it a sporadic event or is it annual?" Mumma said.

But observations from Earth can only tell scientists so much, "ultimately the real test will be to go there," Mumma said.

The Mars Science Laboratory rover, now slated to launch in 2011, has the capability to detect methane, but whether or not it will have the chance to is another story.

"It may go to a site that is not actively releasing gases," Mumma said.

- New Device Could Solve Mars Methane Mystery

- Mars Madness: A Multimedia Adventure!

- Images: Visualizations of Mars

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.