Polluted Star Hints at Water's Origins on Earth and Alien Planets

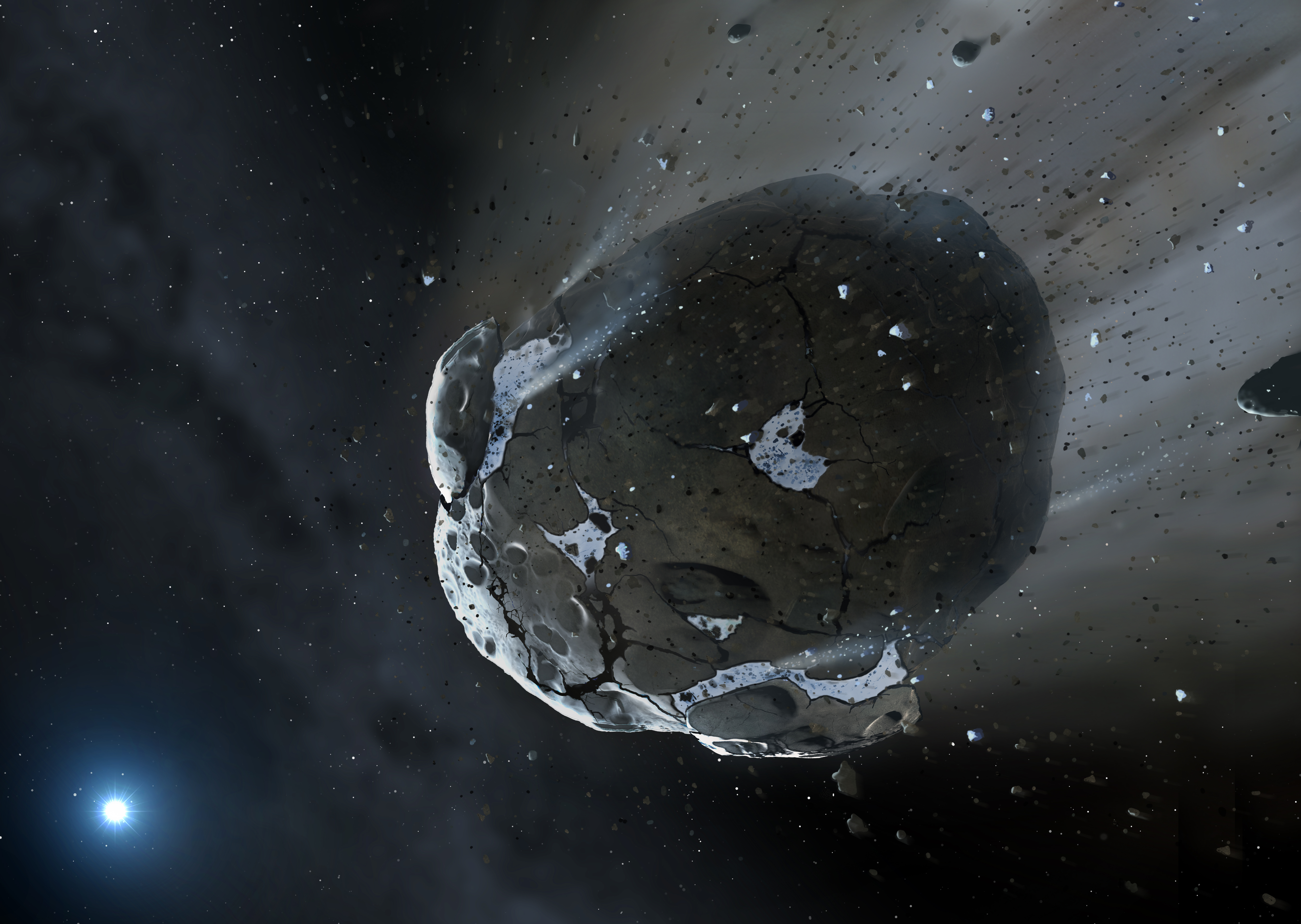

Astronomers have spotted a dead star polluted with heavy elements, suggesting that the star recently chowed down on a water-laced asteroid.

The destructive process hints at how asteroids probably delivered water to Earth billions of years ago. But it also hints at how asteroids likely deliver water to exoplanets in other planetary systems.

"Our research has found that, rather than being unique, water-rich asteroids similar to those found in our solar system appear to be frequent," lead researcher Roberto Raddi from the University of Warwick, said in a statement. "Accordingly, many planets may have contained a volume of water, comparable to that contained in the Earth." [Related: In Search for Alien Life, Follow the Water]

Astronomers once thought that white dwarfs — the Earth-size remnants of low-mass stars like our sun — were pristine. Their intense gravity should pull the heaviest elements down into their depths relatively quickly (thousands of years at most). "In old white dwarfs (hundreds of millions of years old), like the one we observed, one would not expect any heavy element to stay in their atmospheres for long," Raddi told Space.com in an email.

But when the team observed the white dwarf in question (known as SDSS J1242+5226), they saw that it was smothered in oxygen, magnesium, silicon, iron and other heavy elements. Even hydrogen was far more abundant than expected. These elements match what astronomers expect to see in a water-rich asteroid.

It’s likely that the asteroid passed close to the white dwarf, whose intense gravity shredded it into smaller particles. These particles then formed a disk around the dead star, and slowly rained down over time — polluting the star's surface with its elements. Because those elements are still expected to sink to the center of the star, the destructive event probably happened fairly recently, Raddi said.

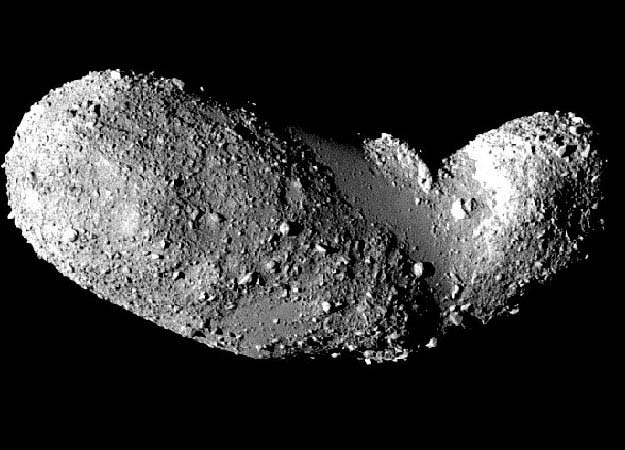

The astronomers suspect that the asteroid was initially comparable in size to Ceres, the largest known asteroid in the solar system, Raddi said. And it likely contained enough water to fill 30 percent of the Earth's oceans.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And this research shows that this process was not unique to our solar system. It's likely occurring throughout planetary systems in the galaxy, scientists said.

"Our work reinforces previous evidence that water-rich asteroids are common in other planetary systems," Raddi said. "It also confirms that asteroids can deliver their constituents (rocks and ice) onto the surface of planets in the inner parts of the planetary systems orbiting other stars, likely within what is known as the habitable zone."

The team made their observations on the U.K.-owned William Herschel Telescope in the Canary Islands, Spain. The study was published today (May 7) in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow Shannon Hall on Twitter @ShannonWHall. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Shannon Hall is an award-winning freelance science journalist, who specializes in writing about astronomy, geology and the environment. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scientific American, National Geographic, Nature, Quanta and elsewhere. A constant nomad, she has lived in a Buddhist temple in Thailand, slept under the stars in the Sahara and reported several stories aboard an icebreaker near the North Pole.