Astronauts May Suffer Artery Damage on Long Missions

At least some astronauts who spend six months aboard the International Space Station come back to Earth with stiffer arteries than before their flights, a new study reveals.

Stiff arteries in seniors here on Earth can lead to higher blood pressure and, potentially, problems with blood flow to the brain. But no blood pressure changes in astronauts have been noted so far, scientists said.

"In an older person, that means that the blood pressure that reaches the brain, for example, is elevated," Richard Hughson, lead author of the research and a vascular aging researcher at the University of Waterloo in Canada, told Space.com in a phone interview. "You're putting higher pressures on the smaller, more fragile blood vessels that are in the brain and potentially damaging them." [The Human Body in Space: 6 Weird Facts]

The research — which included participation from Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield— was presented Tuesday (June 17) during the one-day Aging in Space for Life on Earth Symposium at the University of Waterloo.

The study looked at a small sample of nine astronauts, but the research is based on data from just the first four examined in orbit. The remaining five samples returned to Earth on SpaceX's Dragon cargo spacecraft a month ago and are still being analyzed.

Toward one year in space

Long-duration spaceflight is hard on the human body; some researchers even call time in weightlessness an accelerated aging process. Despite exercising a couple of hours a day on the International Space Station, astronauts still suffer weakened bones, atrophied muscles and other problems usually associated with seniors. It takes rehabilitation on Earth to fight back against these problems.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Some astronauts even experience changes in their eyesight, to the extent that some go up to space with perfect vision and then find out they need glasses when they return to Earth. Figuring out what's going on is key for NASA, which hopes to send astronauts on lengthy missions to Mars about 20 years from now.

Health issues will also get attention when two people spend a year on the International Space Station, beginning in 2015.

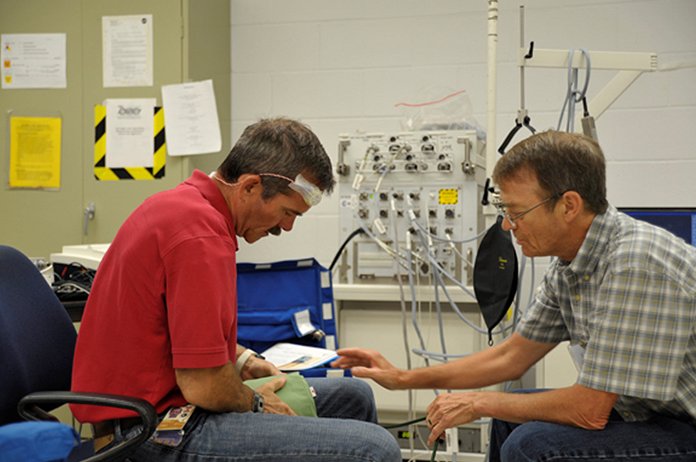

Hughson's study used ultrasound to measure artery stiffness in the neck about two months before and then one day after spaceflight (when the astronauts returned to NASA's Johnson Space Center after their flight from the landing area in Kazakhstan).

In orbit, the astronauts took two samples of their own blood, then put the samples in cold storage. Upon return to Earth aboard Dragon, researchers analyzed these samples for "biomarkers" (chemical compounds or proteins) that could be related to the changes in arteries.

Elastic arteries

It's believed that stiffer arteries change blood pressure because of the way artery walls absorb the energy from each heartbeat. In younger people, the walls are more elastic and can thus absorb the pressure. In seniors, that ability is reduced.

While it's believed this could in turn cause increased pressure in the brain, researchers don't know this for sure. If a link exists, it could lead to health problems among astronauts such as dementia or vascular cognitive impairment, scientists said.

Hughson cautioned that stiff blood vessels in the neck may not reflect what's happening in the entire body. In spaceflight, blood pressure equalizes across the body, whereas on Earth, gravity pulls pressure more toward the legs. So it's possible some arteries may become less stiff in orbit.

"We did a slightly different measurement, looking at the arteries between the heart and the ankle, and we didn't really find a change," he said.

For this measurement, the scientists looked at how quickly the pulse wave travels through the body after every heartbeat. Hughson is now applying to do a follow-up study on astronauts and is also analyzing work related to "BP Reg" — a study of astronauts' blood pressure in orbit.

A separate presentation at the conference Tuesday by Jens Titze, an associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University in Tennessee, showed that salt intake in the body cycles up or down independent of how much salt the person consumes.

"This very simplistic view — salt is always constant, and if you eat more, your body volume increases — this is far too simple," he told Space.com.

Some of that research was based on a study Titze did of crew members in Mars500, a simulated mission to the Red Planet. These participants were on restricted diets, making the measurements easier to accomplish. But Titze cautioned it's too early to apply the research to discussions about how much salt people should consume.

Studies have also linked salt storage to autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis, as well as age-related issues such as heart disease and arthritis, Titze added.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.