Mock Mars Mission: How to Simulate the Red Planet on Earth

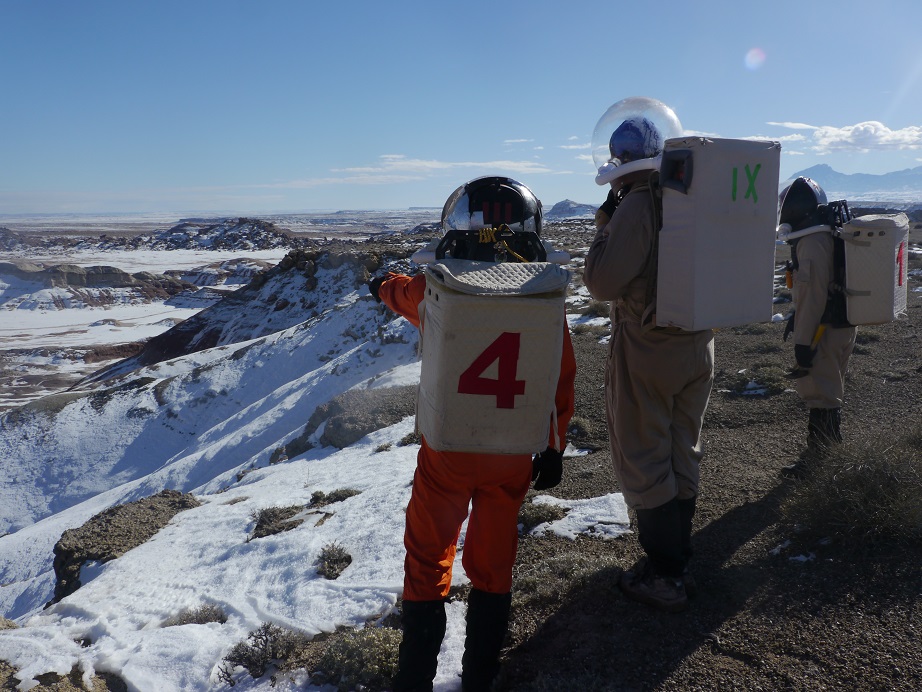

Editor's Note: In the Utah desert, scientists attempt to recreate what a real-life mission to Mars might be like. In January, SPACE.com contributor Elizabeth Howell hitched along with Crew 133 for the ride. She sends this look back at how to emulate a Martian environment on Earth.

While working at the Mars Desert Research Station in rural Utah for three weeks in January, Crew 133 needed to observe several rules to make the simulation as realistic as possible.

As participants at the Mars Society facility, we needed to do everything possible to feel as if we were working on the Red Planet while performing our experiments and doing our daily chores. Once we entered simulation, most of us were allowed outside only while wearing a spacesuit. (There are some limited exceptions to that rule, such as for the crew engineer's daily rounds as he takes measurements on the usage of water and other consumables.)

We also had a three-minute period in the "airlock" (the door to the outside) where we simulate the oxygen pre-breathing procedures astronauts go through to purge nitrogen from their bloodstream. In space, there's a chance that crippling bubbles in the bloodstream could form if the astronaut ventures outside without doing this, which can lead to a painful problem called "the bends." [See photos of the mock Mars mission]

Water in the habitat was monitored and limited. Crewmembers could only take a shower every second day for about two minutes, at most. We also were urged to flush the toilet only occasionally and to turn off the water while brushing our teeth. The only time we were encouraged to use lots of water was for drinking, because the desert makes for a very dry environment inside the MDRS habitat.

The Internet was limited for most of the day, and uploads and downloads took a while. We stopped all automatic updates on our computers. This meant that we couldn't use Skype. As soon as we entered the habitat, we also were told to turn off our cell phones or to put them into airplane mode to make sure that we were not unnecessarily using bandwidth.

We weren't allowed to make cell-phone calls because that would not be an accurate simulation of Mars to Earth communications, where there would be a 20-minute time delay on average. Every night, crew members spent two hours communicating with a volunteer "Mission Control" by e-mail, but no time delay was introduced in these e-mails because of the time it would take.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

While we were allowed to bring food on site, nothing perishable was allowed — so no salads, fruits, vegetables or the like unless they are dehydrated. The Mars Society gave us two large bins — so large that each is best carried by two people — of granola bars, pasta, powered liquids, chocolate, spices and lots of other types of food of this sort. Our crew did a junk-food run just before coming on site, so we had a stash of candy, cookies and chips ready when we needed something different.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.