Weird Orbits of Pluto's Moons Caused By Huge Collision

The odd orbits of Plutos five known moons may be the result of a gigantic impact that occurred about four billion years ago, a new study reports.

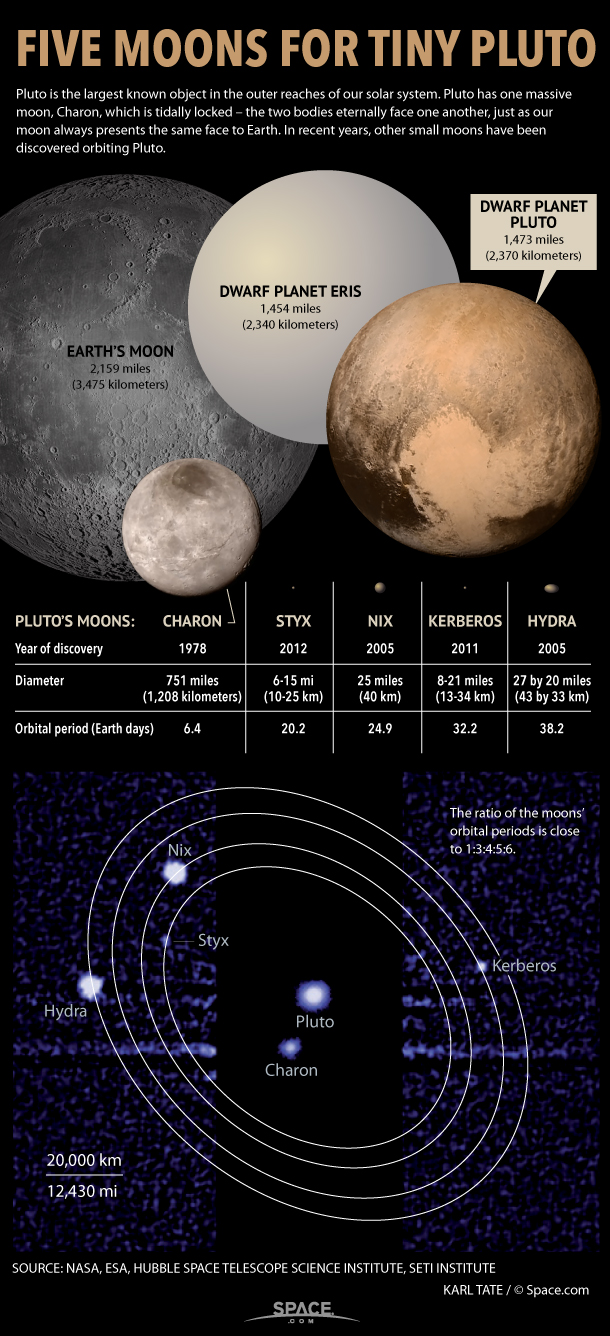

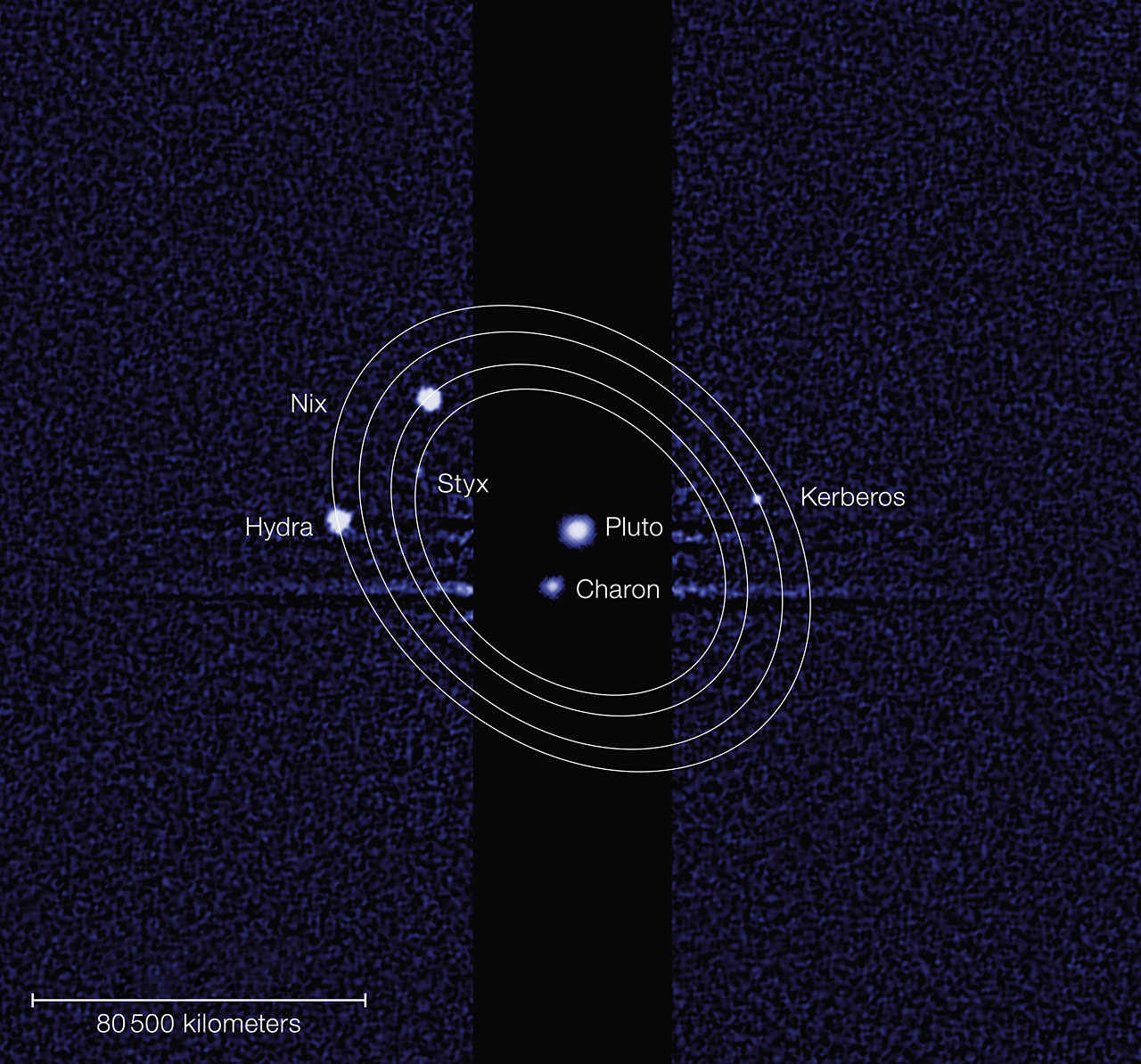

The huge collision that formed Pluto's largest moon, Charon, likely led to the creation and destruction of numerous smaller satellites shortly thereafter, researchers said. This series of events eventually culminated in the strange configuration seen today, in which Pluto’s four tiny moons — Styx, Nix, Kerberos and Hydra — have orbital periods almost exactly 3, 4, 5 and 6 times longer than that of Charon, respectively.

"The implications for this result are that the current small satellites are the last generation of many previous generations of satellites," study co-author Kevin Walsh, of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colo., said in a statement. "They were probably first formed around four billion years ago, and after an eventful million years of breaking and rebuilding, have survived in their current configuration ever since." [Photos of Pluto and its Moons]

At 750 miles (1,207 kilometers) wide, Charon is by far the largest of Pluto's moons (and about half as wide as Pluto itself). The other four satellites range from a few miles across to a few dozen miles in diameter, though their sizes are tough to pin down precisely.

Scientists have long been puzzled by the orbital arrangement of these five moons. Previous models of Charon’s formation have successfully predicted the concomitant creation of smaller satellites as well but could not explain how these minuscule moons moved outward from Pluto without exiting the dwarf planet system or crashing into Charon, researchers said.

"This configuration suggests that we have been missing some important mechanism to transport material around in this system,” lead author Hal Levison, also of SwRI, said in a statement.

The new study, which modeled the early days of the newly formed Pluto/Charon system, may have identified such a mechanism.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Levison and his team found that newly created small moons could be slingshotted outward from Pluto by Charon’s substantial gravity. Further, the frequent collisions among these tiny bodies could have changed their orbits, keeping them away from the system’s largest moon.

In the aftermath of the huge Charon-forming collision, then, multiple generations of smaller satellites were likely created and destroyed, their pieces moving outward and coming together once again to form new moons of Pluto.

Levison presented the findings today (Oct. 9) at the American Astronomical Society's Division for Planetary Sciences 45th annual meeting in Denver.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.