Now Boarding: The Top 10 Private Spaceships

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Introduction

Visions of humanity's future in space almost feature private industry driving a space economy alongside government agencies. In the last few decades, that vision has come closer to reality, especially in the realm of commercially built spaceships.

Multiple spaceflight companies (some of them backed by billionaire investors) are now vying to take astronauts and tourists into space. Some are pursuing innovative flight concepts; others have found what they hope are superior materials to go with tried-and-true spaceship strategies. What follows is a list of some of the most interesting concepts in private space launches and a look at the spaceships companies want to use to take humans and their industries into orbit — and beyond.

(This slideshow was updated Oct. 16, 2017.)

SpaceX's Dragon

SpaceX's Dragon capsule is designed to take cargo — and eventually crew — to the International Space Station. In October 2012, it become the first commercial spacecraft to make a delivery to the orbiting laboratory, and is one of three companies holding a cargo delivery contract for NASA. SpaceX designed the Dragon to be reusable in order to reduce the costs associated with building a new spacecraft for every flight.

The crewed version of the Dragon can hold up to seven people. The craft, like its cargo counterpart, will launch to space atop one of SpaceX's Falcon rockets, and would make soft landings by splashing down in the ocean, similar to the Apollo human spacecraft flown by NASA.

In 2015, NASA awarded SpaceX a $2.6 billion contract to build a crew-capable spacecraft, and flight tests of the vehicle are scheduled to begin in 2018.

Boeing's CST-100 Starliner

Boeing's CST-100 Starliner crew capsule is designed to carry astronauts to and from the International Space Station and low-Earth orbit. It's designed for seven passengers. Boeing says the capsule design harks back to the Apollo-era crew capsule designs, to take advantage of proven technology, according to the company's website. It's also designed to be re-usable, though for only 10 flights, according to Boeing. Like the Russian Soyuz spacecraft, it can make ground landings with a parachute and air bags. It can also splash down in emergencies.

Along with the SpaceX Dragon cargo craft, the CST-100 Starliner is one of two vehicles currently making deliveries to the space station. The human-rated version of the CST-100 was originally expected to be operational in 2017, but test flights are now scheduled to begin in 2018. The delays were due to problems in producing some components of the capsule; a report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office said even that deadline might be pushed back.

Blue Origin's New Shepard

New Shepard is a project of Blue Origin, the company founded by Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos. New Shepard suborbital rockets are fully reusable, and are able to make soft, vertical landings after sending their payloads skyward. New Shepard's reusability is an important factor in cutting the cost of space travel and transport, Bezos has said.

The capsule that rides atop the rocket was designed for space tourism, offering passengers 4 minutes of weightlessness and a view of the Earth through what the company says are the largest windows to ever go into space. While the booster has been successfully launched and landed several times, crew tests are still in the future. Bezos said in March 2017 that the first crewed flights will likely come in 2018, but he also emphasized that the company wants to make sure the craft is fully tested before it puts any humans on board.

Sierra Nevada Corp.'s Dream Chaser

The Dream Chaser, built by Sierra Nevada Corp., is a lifting-body spacecraft, meaning it is designed like an airplane, with wings that can provide some lift. The craft was designed to be launched atop an Atlas V rocket and land on a conventional runway, similar to NASA's space shuttle. If successful, it will reach low-Earth orbit, and be able to dock with the International Space Station. The company is working on a cargo version of the vehicle that can carry 12,125 pounds (5,500 kilograms), and a crewed version that can carry seven passengers.

The Dream Chaser suffered a setback in 2013 when, during an uncrewed test flight, the landing gear failed and the craft skidded off the runway as it landed. On Aug. 30, 2017, the vehicle underwent a "captive carry" test, in which a helicopter carried the Dream Chaser and tested it against some of the conditions it will experience in a more complete test flight, while computers on board collected data.

Sierra Nevada was one of three companies to get a contract from NASA to deliver cargo to the International Space Station, part of the second round of commercial resupply contracts awarded by the space agency. The contract stipulates that the Dream Chaser must complete at least six flights between 2019 and 2024. Company officials have said they expect the first mission to the orbiting laboratory to take place in 2020.

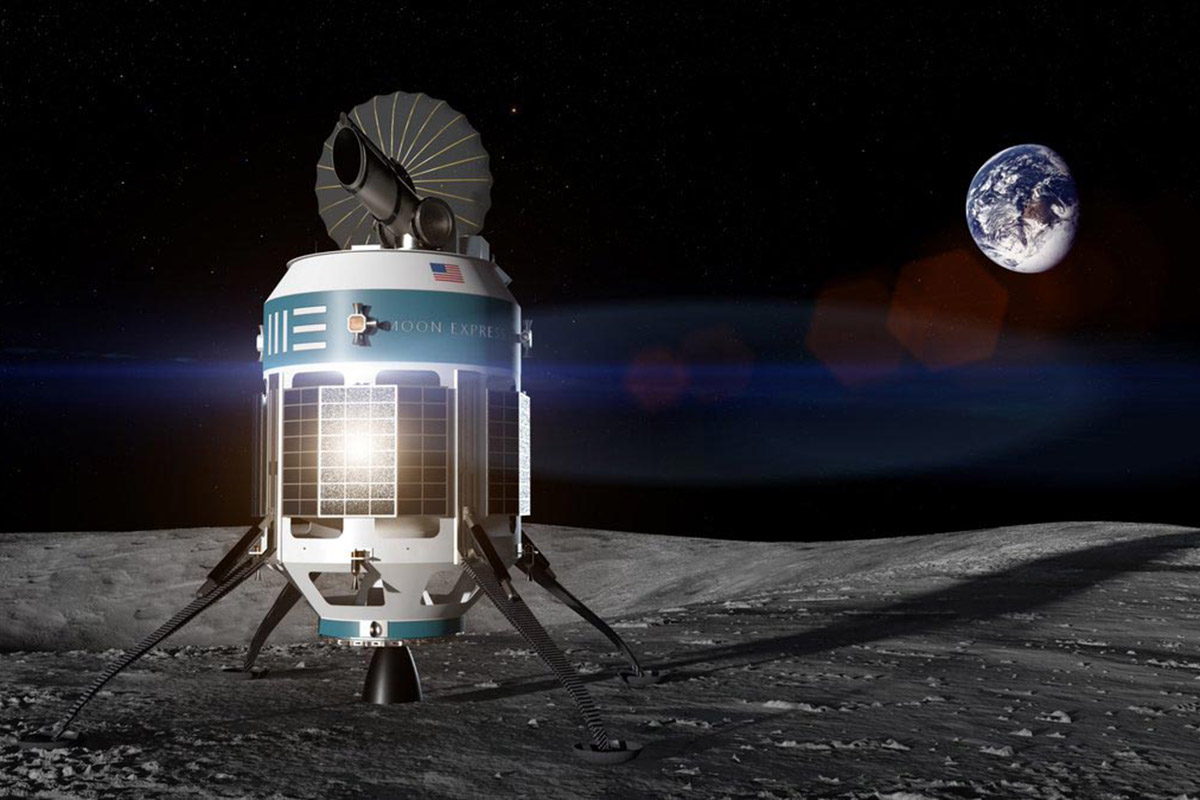

Moon Express' MX-1E

Moon Express, if successful, might be the first private company to get a lander to the moon and back. In testimony before Congress in September, the company said it plans to launch its MX-1E lunar lander in 2018. MX-1E stands about as tall as a person and can carry up to 66 pounds (30 kilograms) to the moon. In addition, its engines allow it to make short hops from one place on the lunar surface to another. The company is in the running for the $30 million Google X Prize, which will be awarded to a team that can get a lander to the moon that travels at least 500 meters across the surface and sends back pictures.

The first mission will carry scientific payloads, but company representatives have said that later iterations of the lander will include the ability to mine for samples and bring them back to Earth. The company plans to conduct a robotic mining mission on the south pole of the moon as soon as the 2020s.

On its first flight, the MX-1E will launch atop a vehicle called the Electron, a small-payload rocket from the company Rocket Lab, which is based in California and operates a launch facility in New Zealand.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Stratolaunch's carrier aircraft

Founded by Microsoft executive Paul Allen, Stratolaunch has constructed a plane that looks like two commercial passenger jets joined side by side, with a wingspan of 385 feet (117 meters), a length of 238 feet (72 m) and a tail height of 50 feet (15 m), making it the world's largest aircraft. The craft will be able to launch rockets from about 30,000 feet. Of course, that means the carrier aircraft itself won't go to space itself, but we'll still include it in our list of "spaceships."

The Stratolaunch carrier aircraft is not a radical design — multiple companies and agencies have tried to develop so-called air-launch systems. The spaceflight company Orbital ATK succeeded with its Pegasus rocket, which is launched from a carrier jet. But Stratolaunch will be able to handle a payload of 500,000 pounds, fully fueled, or the equivalent of three Pegasus rockets.

The reusable aircraft has the potential to lower costs because the craft can take off more easily than vertical rockets and "avoid hazards such as inclement weather, airborne traffic and heavy marine activity," according to the company's website. "Stratolaunch's airborne launch platform significantly reduces the risk of costly delays or cancellations."

Powered by six jet engines, it is the first launch-platform aircraft made largely of composites (meaning made up of multiple composite craft), according to the company. In May 2017, Stratolaunch started refueling tests and took the aircraft out of the hangar for the first time.

Virgin Galactic's SpaceShipTwo

Despite a fatal accident in 2014 that killed a test pilot, Virgin Galactic has continued to develop its SpaceShipTwo suborbital vehicle.

The vehicle looks like an airplane with exceptionally long wings that are bent up and back. The craft is 60 feet long (18.3 meters) with a 27-foot (8.3 m) wingspan. Virgin Galactic plans to use the craft for short tourist trips to suborbital space. The spacecraft is carried by an airplane — also built by the company — to an altitude of about 50,000 feet. At that point, the spacecraft's rockets kick in and the passengers (six of them, plus the two pilots) will go to the edge of space. After a short period when the passengers will experience weightlessness, the spacecraft glides back to Earth, similar to NASA's space shuttle.

George Whitesides, the company CEO, said during the Mars Society Convention in Irvine, California, in September 2017, that the company was gearing up for the next phase of flight testing of SpaceShipTwo, though he would not give a timetable for beginning commercial flights. The first SpaceShipTwo vehicle broke apart in midair on Oct. 31, 2014, during a powered flight test. The company has since redesigned the flight systems to reduce the chance of pilot error that caused the accident.

Bigelow Aerospace

Bigelow Aerospace is in the business of building habitats rather than spaceships, but those habitats will be important if humans want to spend more time in orbit and in deep space.

Unlike the living spaces that make up the International Space Station, which have rigid exteriors, Bigelow uses an inflatable habitat design. In June 2017, their first habitat, called the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module, completed a successful year in orbit attached to the space station. The volume of an expandable habitat can be larger than the rocket fairing it gets launched in.

Bigelow Aerospace told Space.com that the company plans to have two of its latest-model expandable space habitats ready to launch by the end of 2020. Each of the modules has about 11,650 cubic feet (330 cubic meters) of interior, pressurized volume.

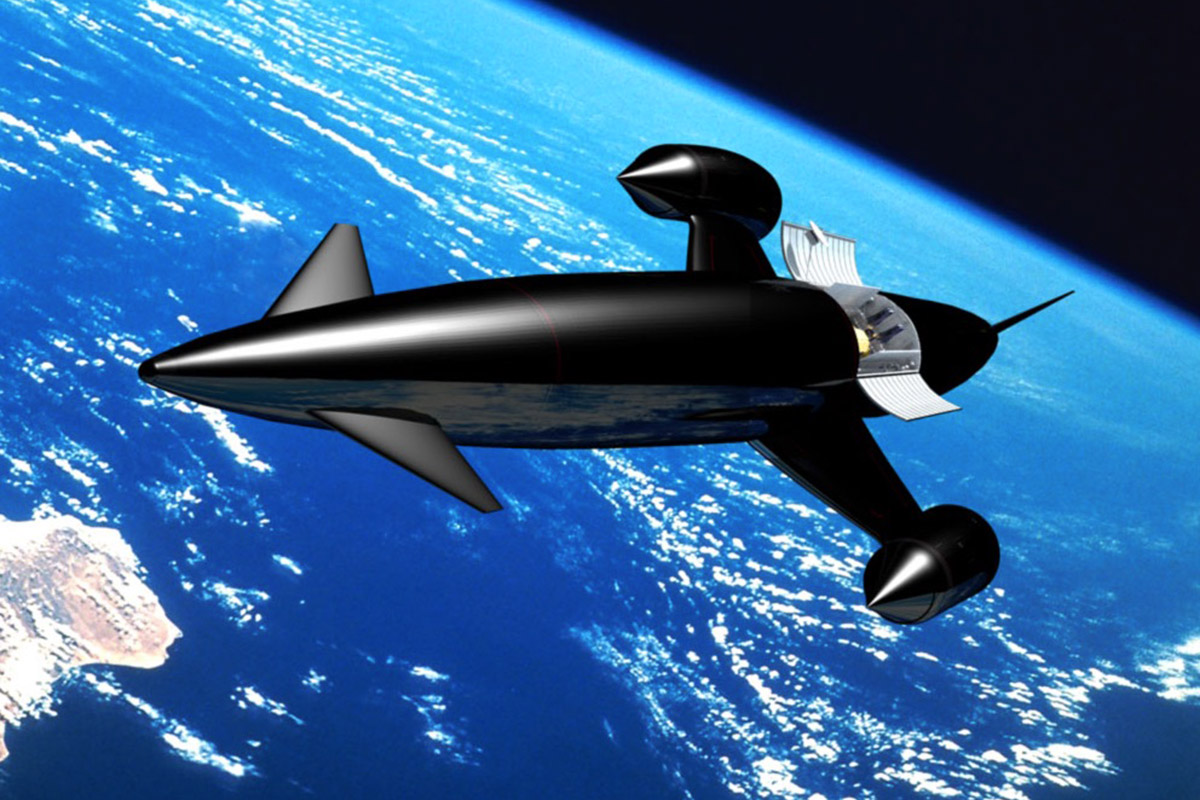

Reaction Engines Limited's Skylon

The concept for Reaction Engines Limited's (REL) Skylon is one that has tantalized engineers for decades: a single stage to orbit (SSTO), launching and landing like an airplane, with the ability to be re-used many times. In that sense it's more akin to the spaceships in movies and science fiction: a sleek vehicle that is streamlined and winged like an airplane and rocket-powered when it gets out of the atmosphere.

Of all the spacecraft on this list, Skylon is probably the furthest from fruition — the company hasn't tested a full-size engine yet, and the company only announced in May 2017 that it would break ground on a $13 million test facility for those very engines.

The Skylon concept is for a spaceplane that uses a Synergistic Air-Breathing Rocket Engine, or SABRE. At low altitudes it flies like a conventional jet, in which the air in the atmosphere ignites the fuel and makes thrust – though for Skylon the fuel is liquid hydrogen rather than jet fuel. At high altitudes, when the air gets too thin to support this process, the craft switches to rocket power to complete the last stage of the trip into orbit, using an on-board oxidizer to mix with the hydrogen to ignite it.

As the Skylon's velocity (and altitude) rises, the incoming air is cooled with a heat exchanger; the heat energy from the exchanger is used to run the fuel pumps. Once Skylon hits Mach 5 and an altitude of about 82,000 feet, the air intakes close and the rockets kick in.

REL admits it may be a long time — perhaps a decade — before a Skylon gets built and flies. In the meantime, the company is pushing the limits of materials science and jet engine design.

You can follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.