Pluto, known for more than eight decades as just a faint, fuzzy and faraway point of light, is shaping up to be one of the most complex and diverse worlds in the solar system.

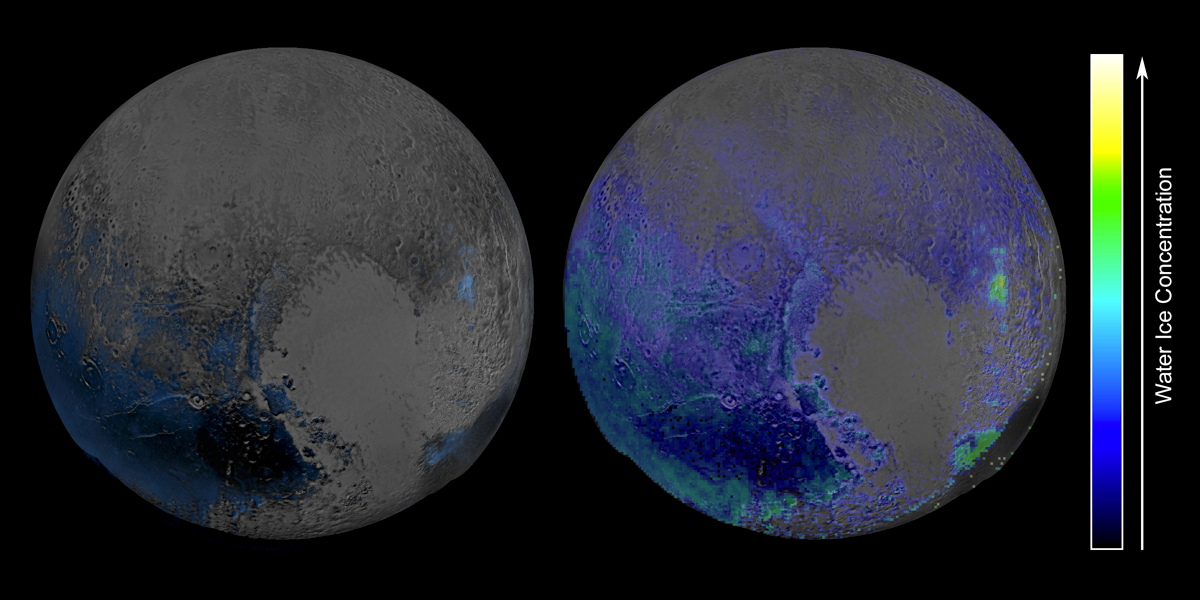

Pluto's frigid surface varies tremendously from place to place, featuring provinces dominated by different types of ices — methane in one place, nitrogen in another and water in yet another, newly analyzed photos and measurements from NASA's New Horizons mission reveal.

"That is unprecedented," said New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, who's based at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. [Photos of Pluto and Its Moons]

"I don't know any other place in the entirety of the outer solar system where you see anything like this," Stern told Space.com. "The closest analogy is the Earth, where we see water-rich surfaces and rock-rich surfaces that are completely different."

That's just one of the new Pluto results, which are presented in a set of five New Horizons papers published online today (March 17) in the journal Science. Taken together, the five studies paint the Pluto system in sharp detail, shedding new light on the dwarf planet's composition, geology and evolution over the past 4.6 billion years.

A distant world coming into focus

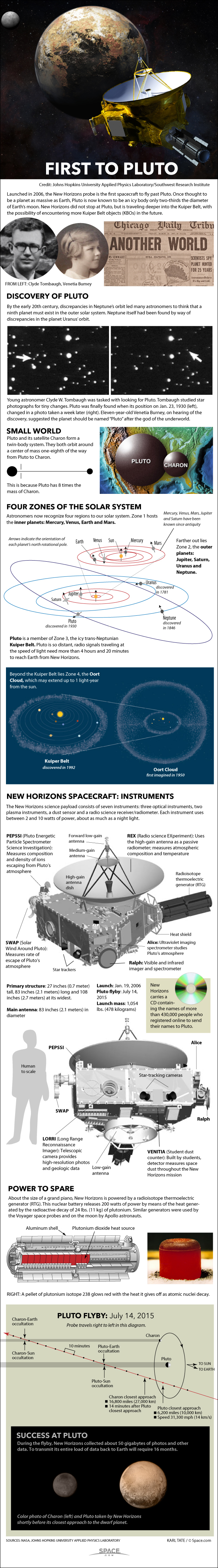

Pluto was discovered in 1930 by American astronomer Clyde Tombaugh. The dwarf planet remained largely mysterious for many years thereafter, because it lies so far from Earth.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

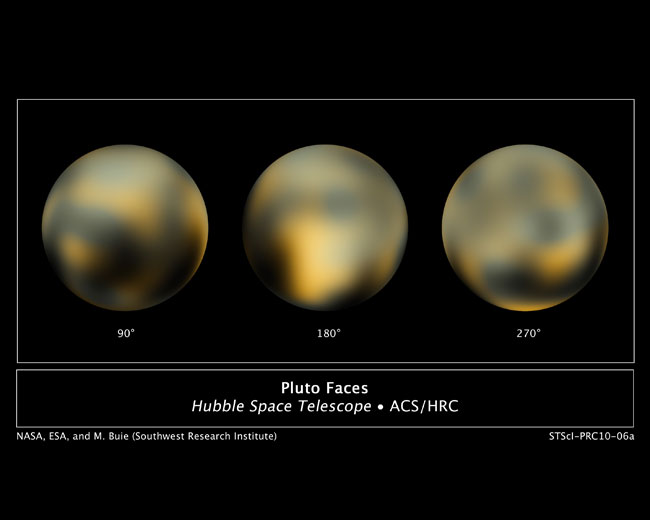

Pluto orbits in the Kuiper Belt, the icy realm beyond Neptune, at an average distance from the sun of about 40 astronomical units (AU). (One AU is the distance from the Earth to the sun — about 93 million miles, or 150 million kilometers.) That's so remote that even the best photo by NASA's famous Hubble Space Telescope portrays the dwarf planet as a mere blur of pixels.

But things began changing in a big way on July 14, 2015. On that day, New Horizons performed the first-ever flyby of Pluto, coming within just 7,800 miles (12,550 km) of its surface. The spacecraft saw towering water-ice mountains; flowing nitrogen-ice glaciers; pebbly "snakeskin" terrain; a vast, crater-free plain known as Sputnik Planum; and many other features that scientists are still trying to figure out.

One of the new papers dives deeply into the geology of these features, revealing new insights about their possible origin and evolution. The 620-mile-wide (1,000 km), nitrogen-ice-dominated Sputnik Planum, for example, apparently sits atop a huge and ancient impact basin, mission scientists say. [Sharpest Pluto Surface View Released by New Horizons Team (Video)]

Sputnik Planum is smooth and pristine, bearing no impact scars. This shows that the region was resurfaced extremely recently — 10 million years ago at most, and possibly much more recently than that, researchers said.

But other parts of Pluto harbor lots of visible craters, and some regions have a middling number, suggesting that the dwarf planet has been geologically active on a large scale over its entire history.

This finding came as a big surprise when it was first announced last year. Earth remains geologically active because it has a hot, molten core. Some icy satellites, such as Saturn's moon Enceladus and the Jovian moon Europa, also harbor substantial internal heat, which is generated by the powerful gravitational tug of their giant parent planets. But something else is likely happening at Pluto.

"I think we have to rethink our whole understanding of geophysics — how you keep small planets active over time," Stern said.

Stern isn't sure what exactly is going on, but he has a favorite hypothesis: that a subsurface Pluto ocean has been slowly freezing over the eons.

"As it freezes, it releases latent heat," he said. "It may be the freezing of this ocean that's powering all this geology."

More geology insights

The new geology paper also discusses and interprets a number of other Pluto features, such as the huge, dark-red Cthulhu Regio — which appears to owe its color to hefty concentrations of tholins, complex organic molecules that drifted down out of the dwarf planet's atmosphere — and the towering peaks Wright Mons and Piccard Mons.

Wright Mons is perhaps 2.5 miles (4 km) high and 90 miles (150 km) wide. Piccard Mons is even bigger, rising about 3.7 miles into the Pluto sky and measuring 140 miles (225 km) across. Both of these peaks may have formed from cryovolcanic activity, the researchers said. [Ice Volcanoes on Pluto? New Imagery Points to It (Video)]

New Horizons also spotted long tectonic faults with very steep associated scarps — characteristics that suggest Pluto has a thick crust composed of water ice, mission team members said.

One of the other new Science papers maps out the distribution of various ices across Pluto's surface. This material — primarily frozen methane, nitrogen, carbon monoxide and water — is deposited in a curiously distinct way, researchers found; some Pluto provinces are dominated by nitrogen ice, others by methane and so on (though there are places, such as Sputnik Planum, where several different ices are found in abundance).

This pattern suggests that volatile material (nitrogen, methane and carbon monoxide) is being moved around by sublimation, condensation and glacial flows on both seasonal and geological time scales, the researchers said.

Surprising atmosphere

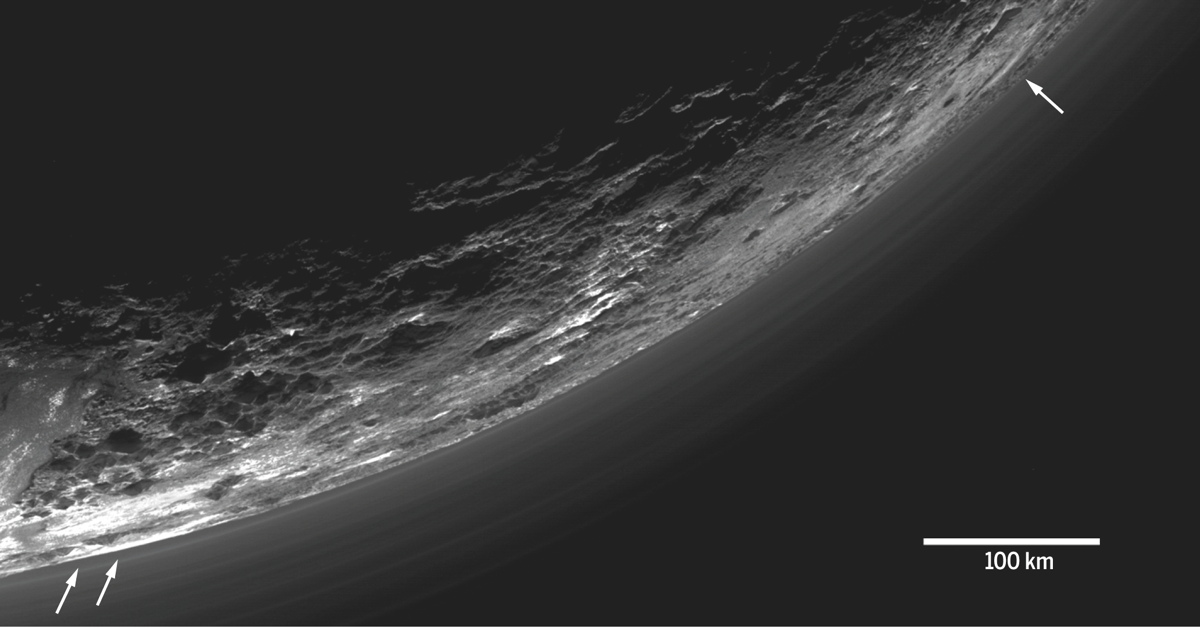

One of the other new Science papers focuses on Pluto's wispy atmosphere. This study also delivered some surprising results.

For example, New Horizons found that Pluto's upper atmosphere — the part that's more than 120 miles (200 km) above the surface — is a lot colder than pre-flyby modeling work had predicted, researchers said. In addition, the dwarf planet is losing its atmosphere at a much lower rate than scientists had thought.

Modeling studies had predicted that Pluto would be outgassing at cometary rates, losing lots of gas molecules to space every second. But New Horizons' measurements showed a mere leak rather than a gush — in fact, the model estimates were off by a factor of about 5,000.

"That shows the power of having a spacecraft there — actually going to see," Stern said.

These twin atmospheric surprises — the cold high-altitude temperatures and the low escape rate — are closely related, Stern added. Cold molecules are less energetic, and are therefore less likely to break free of Pluto's gravitational bonds.

Pluto's moons, too

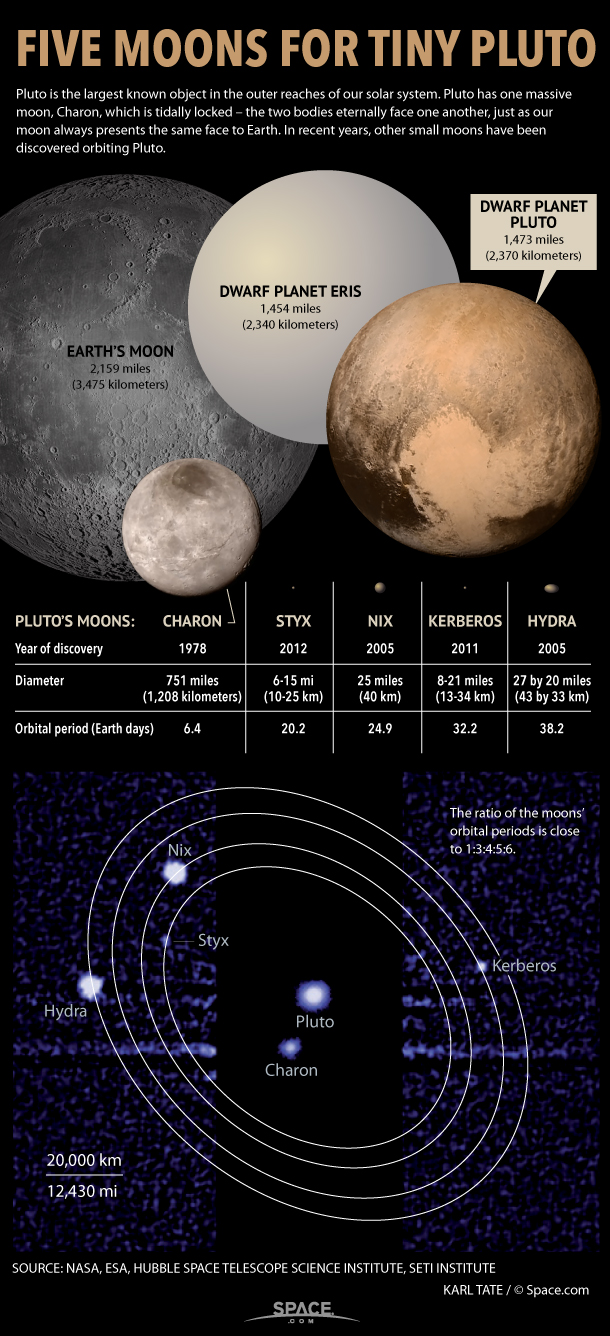

Pluto does not cruise through space by itself. The dwarf planet has five moons — Charon, Nix, Hydra, Kerberos and Styx. The latter four are tiny, measuring just a few dozen miles wide at most, but Charon is 750 miles (1,200 km) across — more than half as wide as Pluto itself. Indeed, scientists regard Pluto and Charon as a binary system.

New Horizons studied these five satellites during its July 2015 flyby, and the new papers provide some insight into their origin and evolution as well.

For example, Charon and Pluto are very different worlds. The big moon shows no evidence of recent geological activity (though it boasts deep canyons, and was probably active until about 4 billion years ago), and its surface is dominated by water ice, with no sign of large-scale movement of volatile ices such as methane and nitrogen.

"Whether this is because Charon's near-surface volatile ices have sublimated and have been totally lost to space, owing to that body's lower gravity, or whether something more fundamental related to the origin of the binary and subsequent internal evolution is responsible, remains to be determined," study lead author Jeffrey Moore, of NASA's Ames Research Center in California, and his colleagues wrote in the Science paper.

In one of the other new studies, Pluto's four smaller moons are examined. These bodies are all quite reflective, suggesting that their surfaces are dominated by water ice, like Charon (but unlike Pluto). In addition, Nix, Hydra, Kerberos and Styx are all spinning quite fast, and their rotational axes are off-kilter compared to those of Pluto and Charon, the authors wrote.

In general, these characteristics bolster the hypothesis that a giant, long-ago impact created the Pluto-Charon binary system, the researchers said. The four small moons are basically shrapnel thrown off by that ancient impact, the thinking goes. (The small satellites are much brighter than typical Kuiper Belt objects, suggesting that they're not pre-existing bodies that were captured by the Pluto-Charon pair.)

More data coming

The five papers, which you can read for free on Science's website, don't represent New Horizons' last word on Pluto — far from it. For example, mission team members plan to present more new results next week at the 47th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in The Woodlands, Texas.

And there's still a lot of flyby data left to analyze. New Horizons has beamed only half of the close-encounter images and measurements back to mission control, Stern said; the entire treasure trove likely won't be on the ground until October.

New Horizons may also perform another flyby that could help scientists better understand Pluto's neighborhood. The spacecraft is currently cruising toward a small Kuiper Belt object called 2014 MU69, which lies about 1 billion miles (1.6 billion km) beyond Pluto. If NASA approves and funds a proposed extended mission, New Horizons will study 2014 MU69 up close on Jan. 1, 2019.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.