What Will Astronauts Do on the Moon When Humans Go Back?

Fifty years after Apollo 11 made history by landing astronauts on the moon, NASA wants to finally go back, but the agency's task list for the mission is still a mystery.

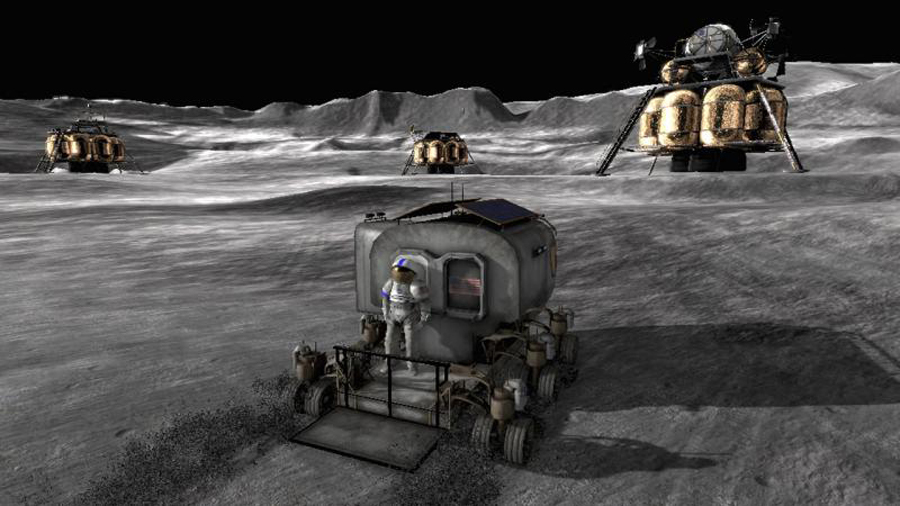

The timeline is set, and aggressively: Land humans on the moon again by 2024, just five years from Vice President Mike Pence's announcement earlier this year. Those humans have a general destination as well: the moon's south pole, a region no human has explored before. And the grand goal is well-touted: Draw on commercial and international partnerships to establish a sustainable human presence on the moon, one that lasts for more than a handful of years as Apollo did.

"One of the first things we have to do is to commit to it not just being a demonstration flight," former NASA astronaut Mae Jemison told Space.com. "When you first go up, you actually do some stuff that allows you to stay longer and allows other people to come."

Related: Apollo 11 at 50: A Complete Guide to the Historic Moon Landing

- Relive the Apollo 11 Moon Landing Mission in Real Time

- Apollo 11 at 50: A Complete Guide to the Historic Moon Landing

- Apollo 11 Moon Landing Giveaway with Simulation Curriculum & Celestron!

But the first landed mission is expected to be short, just a couple of days at most on the moon's surface, designed to prove that the technologies NASA is building or commissioning from commercial partners works the way they are designed to. That list includes rocket, spacecraft, a moon-orbiting station and a spacesuit.

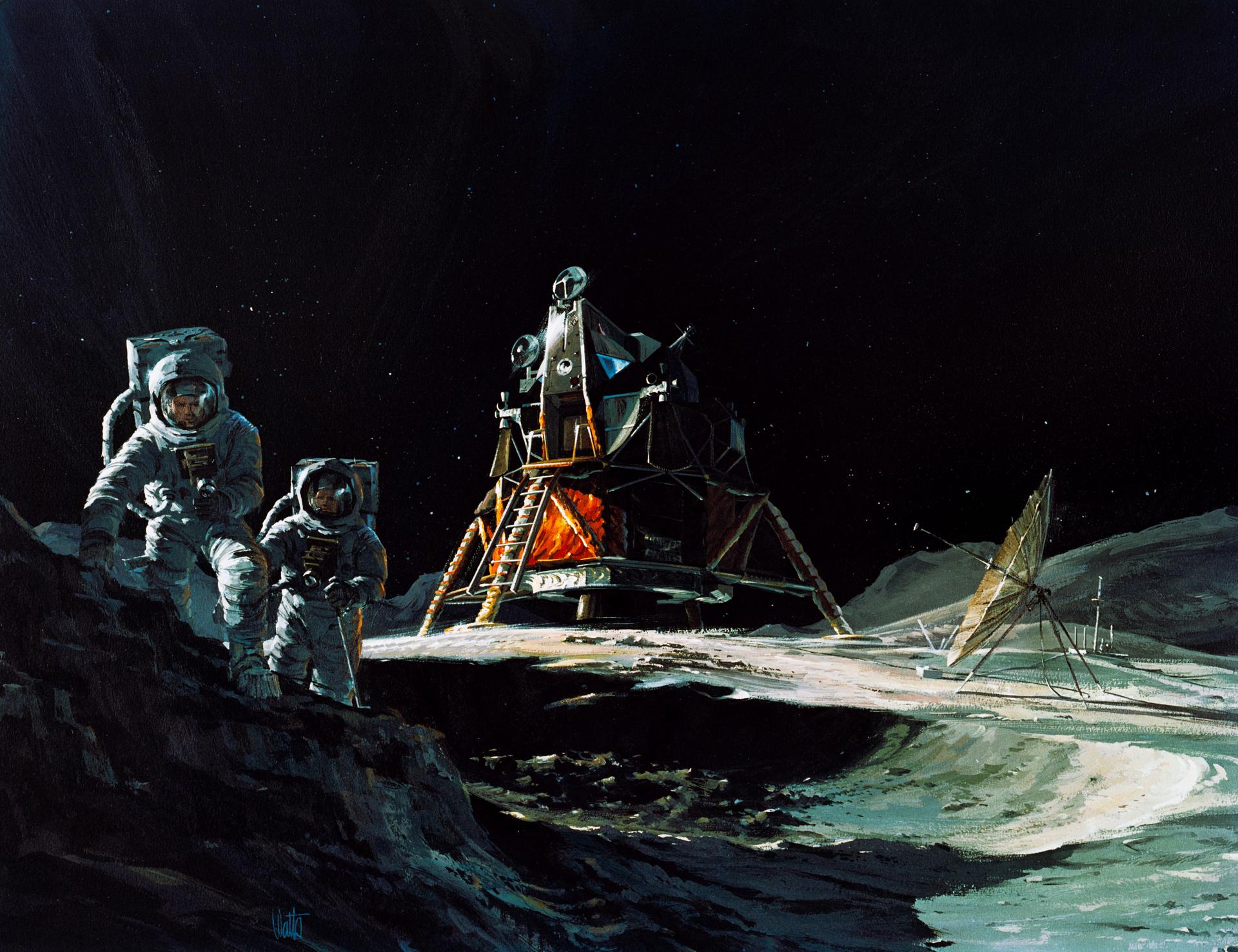

Like the Apollo missions, the next generation of lunar astronauts will be trained for a host of science tasks. Even the best robotic and long-distance missions don't compare to the sort of work humans can do on the ground. That's true even if those robots were to bring back to Earth more moon rocks, like the Apollo samples scientists have busily been studying for decades.

"It would almost be redundant, it wouldn't add a lot of scientific value, to have a robotic lunar sample-return mission," Laura Forczyk, who runs a space industry consulting firm called Astralytical, told Space.com. She sees more potential in human-driven science on the lunar surface, which would progress faster and with more finesse than remote or robotic investigations.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Humans can make better decisions more quickly than robots can," Ryan Watkins, a planetary scientist at the Planetary Science Institute, told Space.com. "You may tell a robotic spacecraft or a rover, 'Hey, go look at that rock,' and they will, they'll go over there and they'll look at that rock, but a human might be walking to that same rock and notice no, the rock over there behind it is actually more interesting — just because they have a better trained eye for that kind of thing."

Astronauts will also be able to deploy instruments that remain on the moon. A particularly intriguing example would be a network of seismometers that could give scientists a look inside the moon in order to better understand its structure and to measure meteorite impacts.

"It doesn't matter where we land, we're going to learn something new," Watkins said. "Whether it's the south pole or not, we're going to learn valuable science. There's a large portion of the moon yet to be explored."

The south pole destination is tantalizing, however, because that's where scientists have identified water ice locked below the moon's surface — and engineers believe that they can harvest that ice through a process called in situ resource utilization. Such technologies would extract the ice and melt it for drinking water for humans, or split it into hydrogen and oxygen to serve as rocket fuel.

Or at least, that's the theory. "It's a chicken-and-egg problem because we believe that this technology can be ready," Forczyk said. "But you can't really know until you test it in situ, until you actually get that technology there." Earth and the moon are just too different when it comes to soil characteristics, gravity, even how fluids behave. But if such technologies do work on the moon, they would also attract companies interested in selling those products, which would entirely reshape the idea of humans on the moon that Apollo created.

Related: Why We Can't Depend on Robots to Find Life on Mars

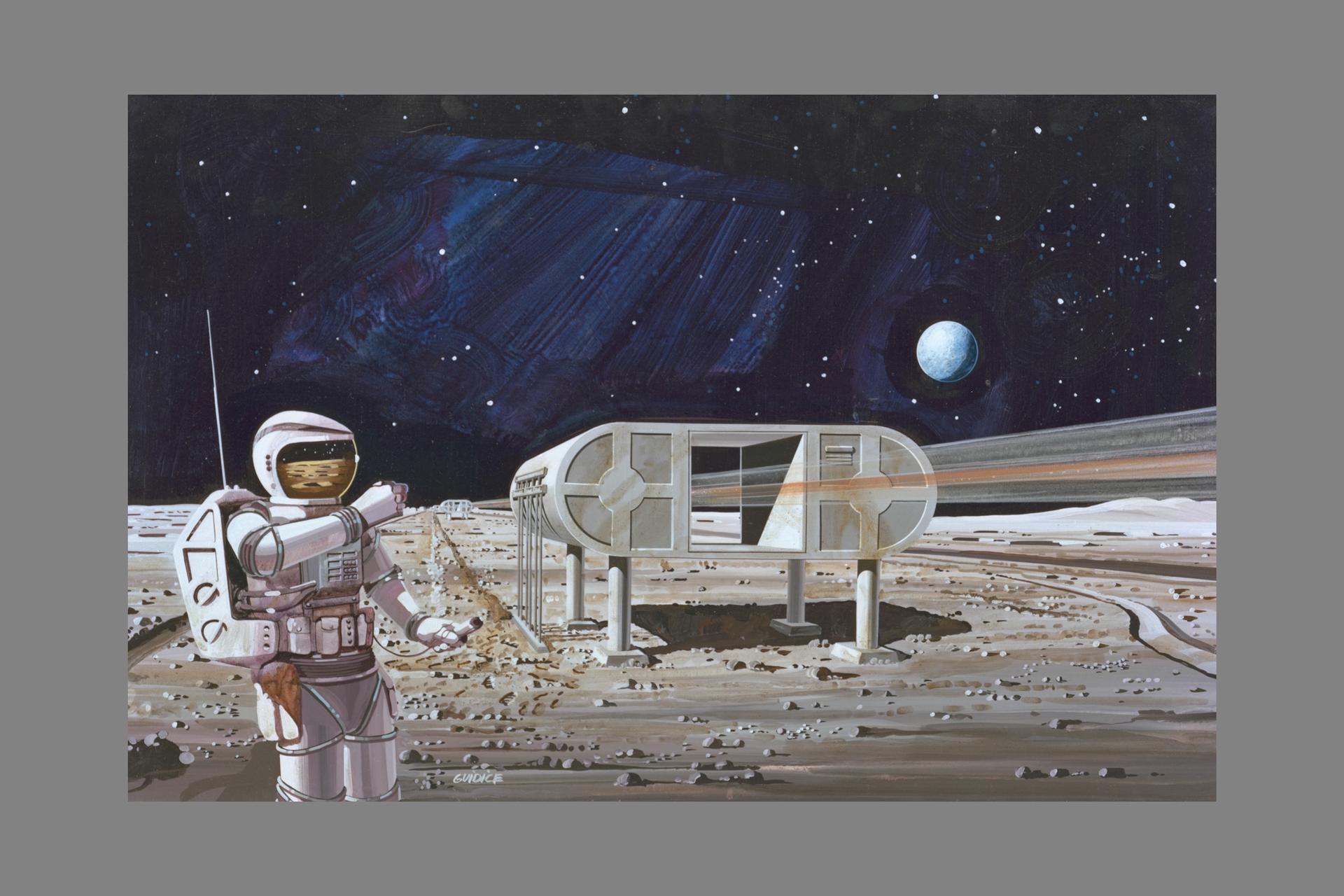

"Sustainable" is still the sticking point. "The problem with Apollo is that it stopped, right, we're celebrating 50 years and it's over," Forczyk said. "The idea is that we want to go forward now and not have it stop, not have just a government whim say, 'OK, mission canceled' after a landing or two or three." Instead, NASA paints a picture of something more like the Antarctic, where countries and academics and companies work together for the long term outside the bounds of an individual nation.

The longer perspective means that scientists and engineers may have to grapple with issues that weren't problematic during Apollo but could easily become so. For example, landing a spacecraft on the moon sends up clouds of dust — and that dust is awfully sharp. "If you're building a lunar base, for example, and you're going to land in the same place over and over again, you're likely going to blow up a lot of dust that could then hit your habitat or instruments or rovers," Watkins said.

The strange dust isn't the only reason why working on the moon won't actually be like working in Antarctica — but the challenges should offer valuable lessons before any potential missions still farther afield, like, say, Mars.

"It's a barren world where we can't just have a camping trip, we have to learn how to work in a completely desolate area," Forczyk said. That means "learning how to work on a planetary surface that does not have the life that we're used to, the microorganisms and the fossil history that we can use for fuel and all of those other things that we're just so used to here on Earth."

But just because technologies begin off Earth doesn't mean they can't improve the lives of those who never step off our planet. "This was true of the Apollo days, a lot of the technologies that were developed then became actually useful for us here on Earth," Watkins said. "It just kind of is a natural flow as we learn how to do things better."

Beyond technology, building up a human presence at the moon may well require learning to get along better together as well. NASA has emphasized that it doesn't want to return to the moon alone — it wants to develop an international system like the one underlying the International Space Station.

That system is about more than space plumbing and coordinating supply launches. "Partnerships that are formed in space can help the geopolitics here on Earth," Forczyk said. "I'm not saying that the moon is some kind of magical geopolitical solution, I'm saying that it's another area where human beings can learn how to partner."

And then, of course, there's one more thing that humans will do if and when they set foot on the moon, the ultimate intangible.

"This isn't the sole reason to go back to the moon, but I do think there's an element of, it's in our human nature to explore," Watkins said. "I think that's a valid reason to go back as well."

- NASA's Historic Apollo 11 Moon Landing in Pictures

- Reading Apollo 11: The Best New Books About the US Moon Landings

- Catch These Events Celebrating Apollo 11 Moon Landing's 50th Anniversary

Space.com contributor Elizabeth Howell contributed reporting to this story. Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.