Watch Venus snuggle up to Neptune for Valentine's Day tonight

The solar system's hottest planet risks the cold shoulder by snuggling up to the ice giant Neptune in the night sky this week.

Valentine's Day is here, and there's no better way to celebrate the holiday than watching the second planet from the sun Venus, named after the Roman Goddess of love, and the ice giant Neptune snuggling up together in the night sky.

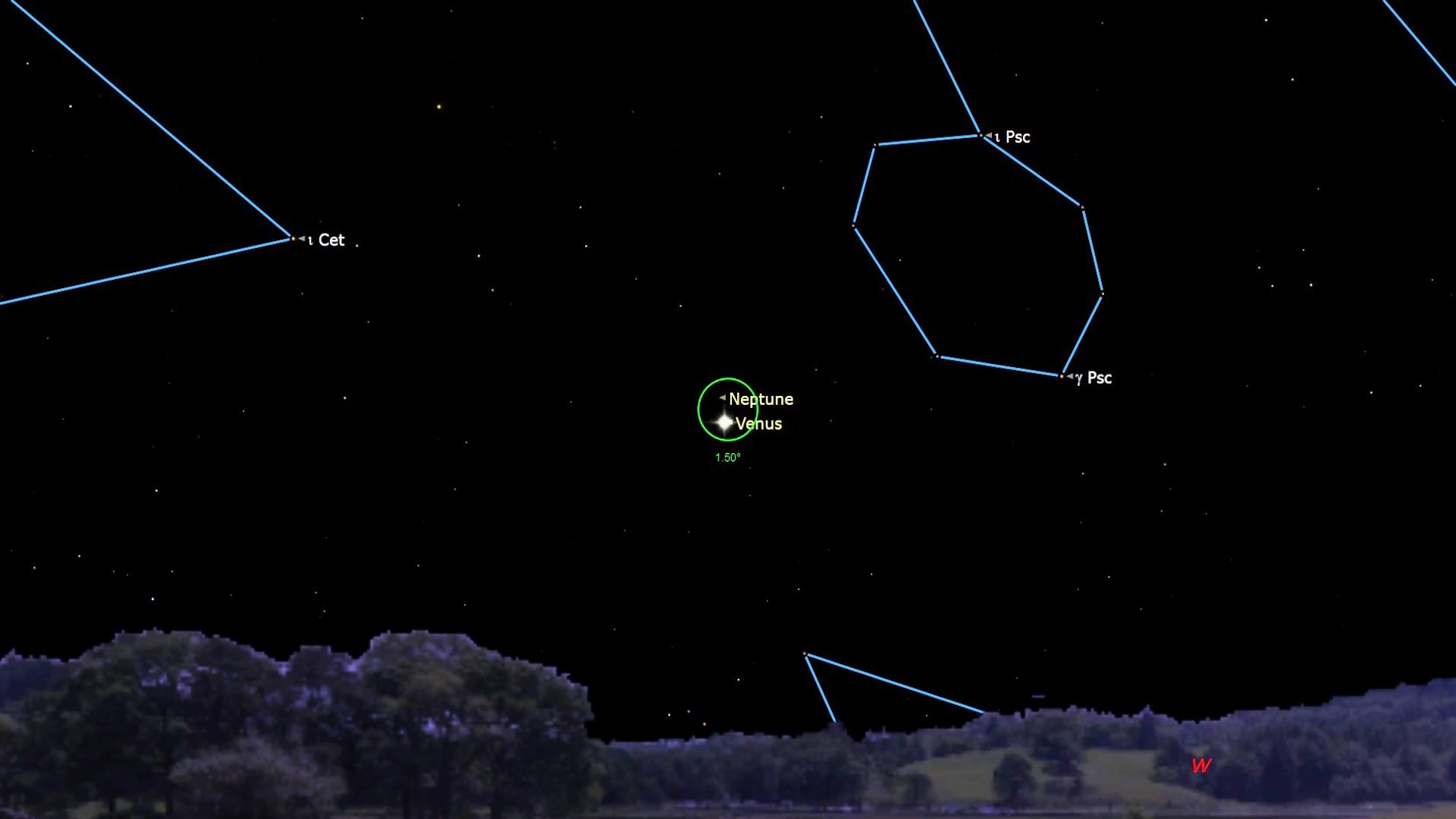

On Tuesday (Feb. 14), Venus and Neptune will join together in the night sky in the early evening. The following day (Feb. 15), the pair will share the same right ascension (the celestial equivalent of longitude) in an arrangement astronomers call a "conjunction."

According to In the Sky from New York City the conjunction between Venus and Neptune will become visible over the horizon to the southwest at around 5:47 p.m. EST (2242 GMT). This cosmic date won't last long, however. The joining of the two will start at around 20 degrees above the horizon before sinking lower and disappearing at around 7:43 p.m. EST (0143 GMT).

Related: Night sky, February 2023: What you can see tonight [maps]

Looking for a telescope to check out Venus or Neptune? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner's telescope guide.

If you don't fancy braving the cold February evening to spot the conjunction (or if you have a hot Valentine's Day date!), then it will also be viewable from the comfort of your own home thanks to the Virtual Telescope Project.

The project's livestream starts at 12:30 p.m. EST (1730 GMT) on Wednesday (Feb. 15) and can be viewed courtesy of the project's website or YouTube page.

During the conjunction on Wednesday (Feb. 15), both planets will be in the constellation of Aquarius. Venus will have a magnitude of -4.0, with the minus prefix indicating a particularly bright celestial object, while Neptune will be quite dim with a magnitude of 8.0.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The planets will be close enough in the night sky during the conjunction to be spotted using a telescope and should also be visible using binoculars. In the Sky gives the right ascension of both objects as 23h38m50s and the declination of Venus as -03°34', while Neptune has a declination of -03°33'.

In terms of conjunctions, it would be pretty difficult to find one comprised of two planets more different than Venus and Neptune. The key difference in this odd couple is one's blisteringly hot conditions and the other's frigidly cold temperatures.

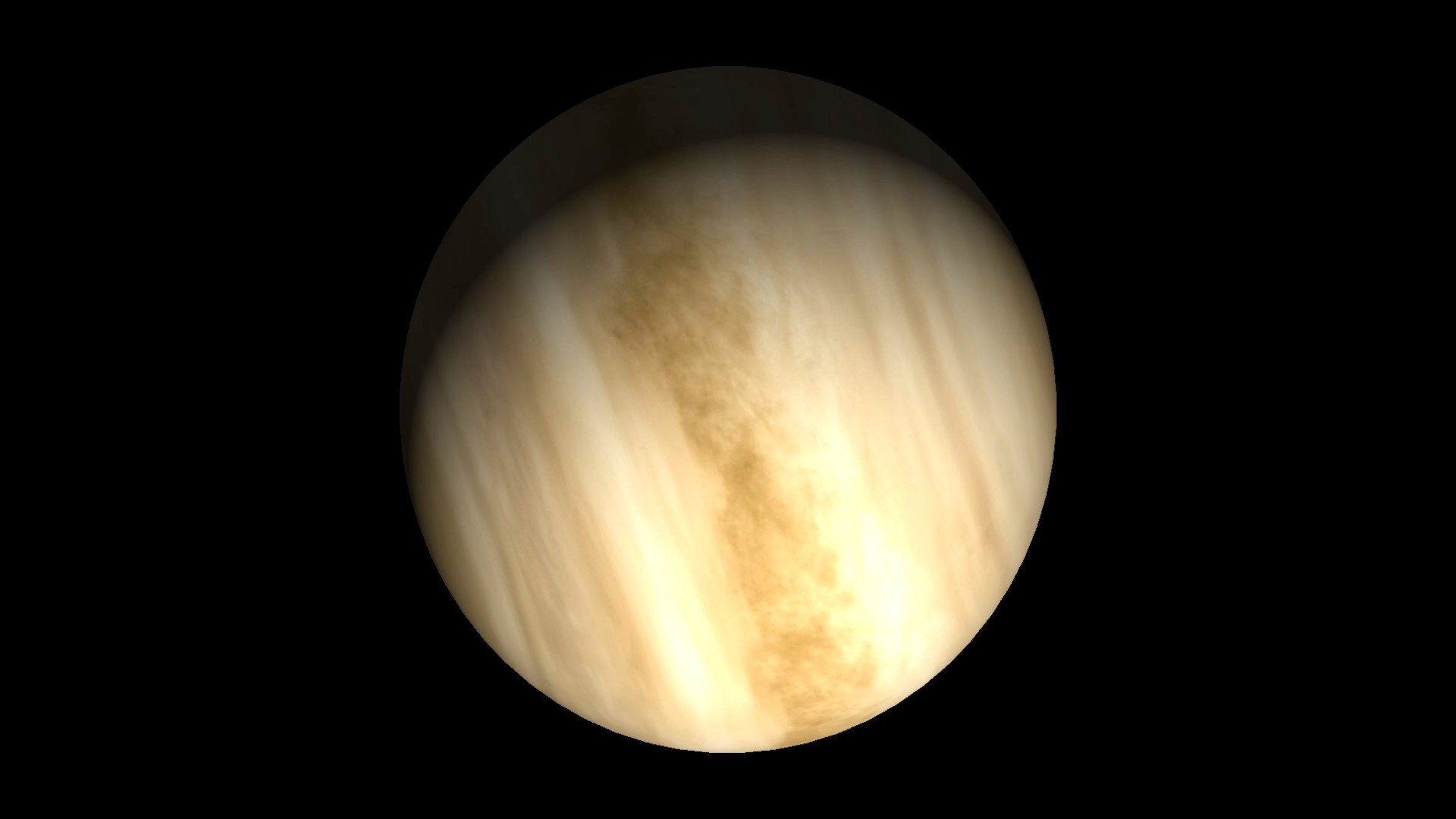

Located around 68 million miles (108 million kilometers) from the sun, Venus is similar to Earth in size, density, and rocky composition. It varies wildly in its surface temperature of 900 degrees Fahrenheit (475 degrees Celsius), hot enough to melt lead, however.

Venus has a rust-red coloration and its believed that its surface is covered with volcanoes, with this volcanism helping to drive the runaway greenhouse effect that occurs in its toxic atmosphere. This makes Venus the hottest planet in the solar system, even though Mercury is closer to the sun.

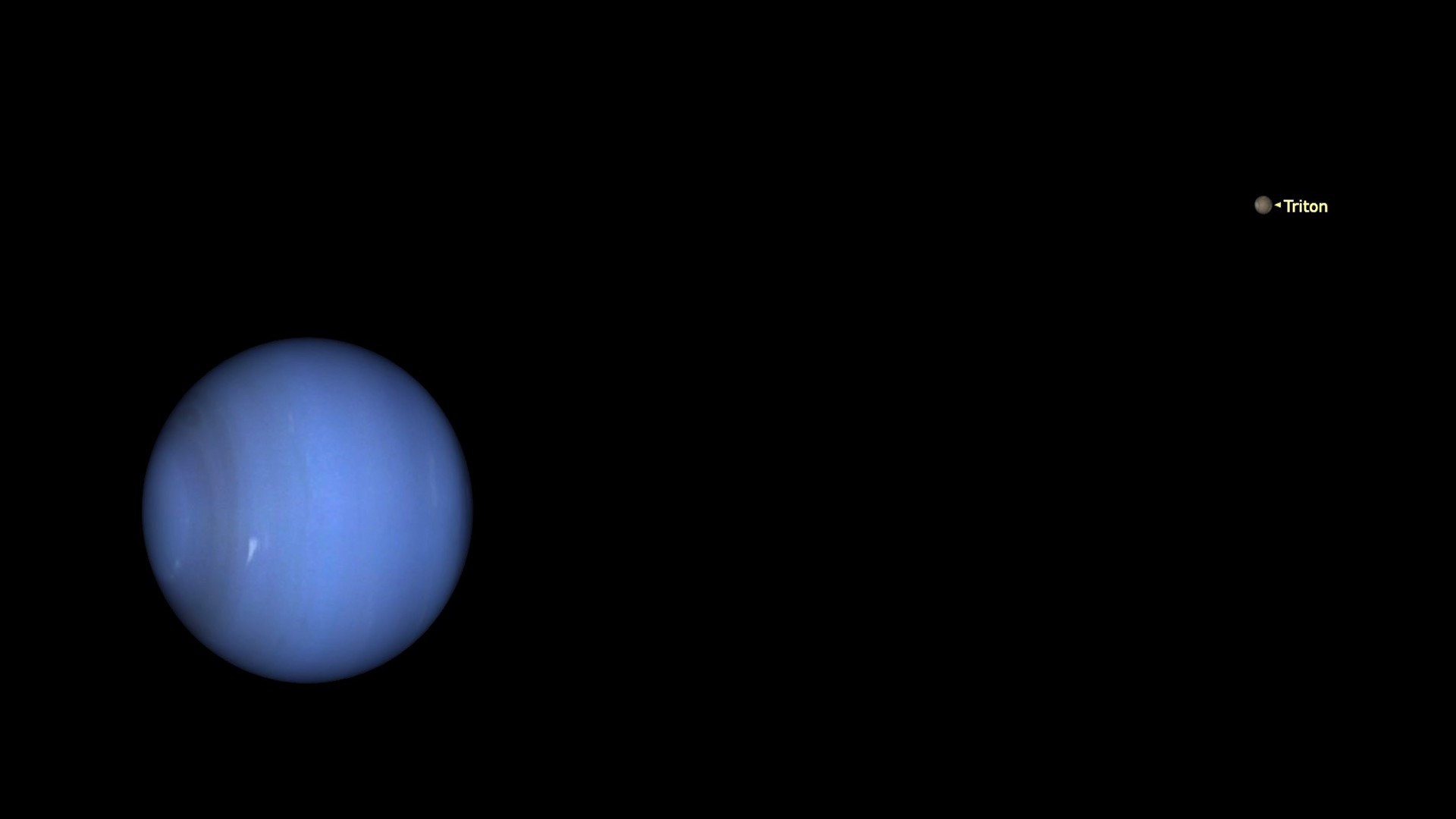

Also named after a Roman god, the god of the sea, the giant planet Neptune is the eighth planet from the sun and is around 2.8 billion miles (4.5 billion kilometers) from our star. This is 30 times the distance between the Earth and the sun and means Neptune takes 165 Earth years to complete an orbit.

Lacking a solid surface, according to Hull University, the temperature on Neptune is brutally cold at around -353 degrees Fahrenheit (-214 degrees Celsius). This doesn't make it the coldest planet in the solar system, however, with its fellow ice giant Uranus considered colder, even though as the seventh planet from the sun it is about a billion miles close to the sun than Neptune.

Venus and Neptune are also wildly different in terms of size. If Venus was shrunk down to the size of a nickel, then the ice giant Neptune would be about the size of a baseball.

One thing both planets have in common is their complete inhospitality to life. This atmosphere doesn't just create incredible temperatures on Venus composed mostly of carbon dioxide; it also creates incredible pressures at the planet's surface that are 90 times that of those on Earth at sea level, with pressures only reaching this level on our planet in the ocean at depths of around a mile.

Meanwhile, in addition to its frigid temperatures, Neptune is subject to incredibly fast wind speeds. Winds at the equator of the planet are around 700 miles per hour, but windspeed rises at the ice giant planet's titanic storm, the Great Dark Spot, reaching extremes of around 1,200 miles per hour.

If you're hoping to catch a glimpse of the conjunction between Venus and Neptune our guides for the best telescopes and best binoculars are a great place to start. If you're looking to snap photos of the night sky, check out our guide on how to photograph the moon, as well as our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Editor's Note: If you snap the close approach or conjunction of Venus with Neptune and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, or on Facebook and Instagram.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.