The Taurid meteor shower of 2020 peaks soon. Here's what to expect.

If skies are clear during this upcoming week, be sure to take a few moments to gaze upward. You just might be lucky and catch a glimpse of a spectacularly bright meteor — a Taurid meteor.

While most meteor showers are noticeably active for about a week, the Taurids have perhaps the longest duration of overall visibility. Meteors from this particular stream begin appearing in our night sky around Oct. 21 and will continue into right on up until or about Nov. 27. Nov. 5 through Nov. 12 is traditionally the time frame when these slow and majestic meteors are at their best.

Unfortunately, in 2020, this display has — so far — been seriously hindered by the presence of a brilliant moon. The moon turned full on Halloween night (the so-called "Blue Moon"). That night, brilliant moonlight flooded the sky much of the night and squelched all but the brightest meteors. Thereafter, however, the moon has been setting later in the evening and has been slowly waning in brightness. Last quarter comes on Sunday, Nov. 8 and thereafter the moon will be a progressively thinning crescent.

Related: How meteor showers work (infographic)

Moonrise on Nov. 5 comes at around 8:30 p.m. local time. But with each passing night, the moon will be rising on average about 68 minutes later and the window of dark sky hours (prior to moonrise) opens a little wider. The overnight hours of Nov. 11 into the morning hours of Nov. 12 is probably the best night to watch the Taurid meteor shower, as the moon — by then a thin waning crescent — will not rise until around 3:15 a.m., leaving about 9 hours of dark, moonless skies for those looking for Taurids.

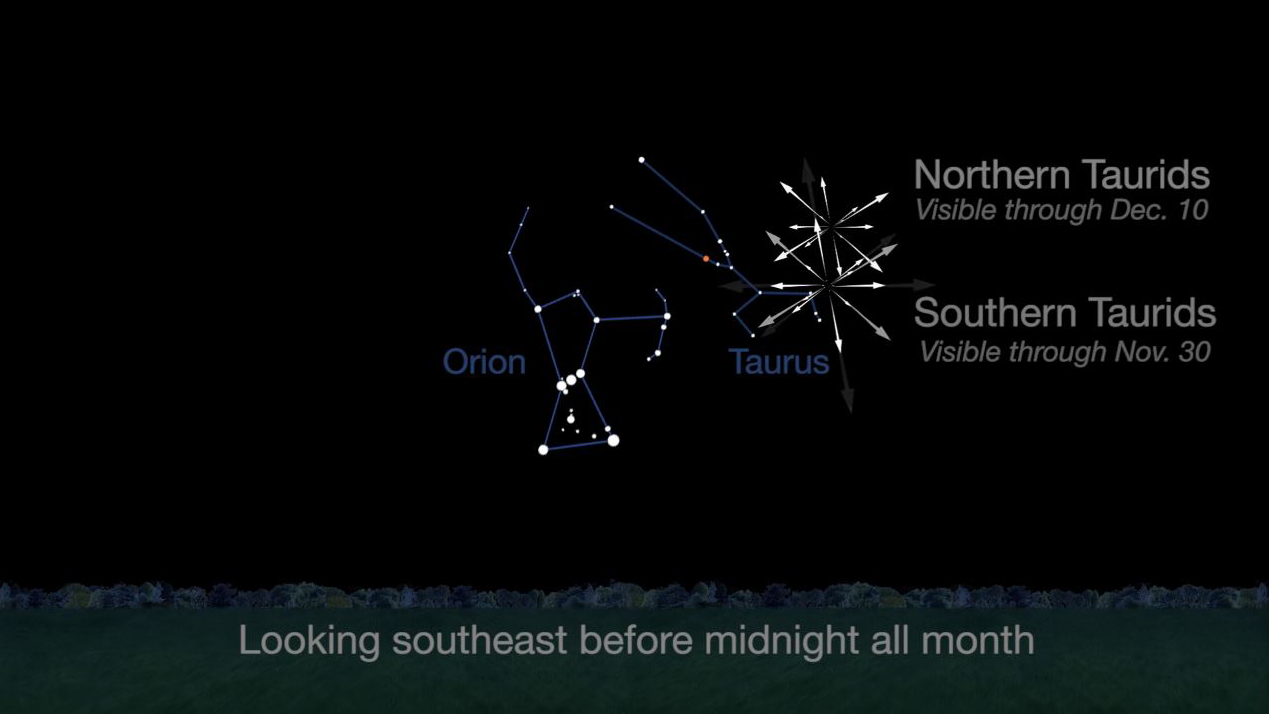

Each evening, up until the time the moon comes up above the horizon up to about 10 to 15 meteors may appear per hour. They are often yellowish-orange and, as meteors go, appear to move rather slowly. Their name comes from the way they seem to radiate from the constellation Taurus, the Bull, which sits low in the east a couple of hours after sundown and is almost directly overhead by around 1:30 a.m.

Meteors — popularly referred to as "shooting stars" — are generated when debris enters and burns up in Earth's atmosphere. In the case of the Taurids, they are attributed to debris left behind by Encke's Comet, or perhaps by a much larger comet that upon disintegrating, left Encke and a lot of other rubble in its wake.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And indeed, the Taurid debris stream contains noticeably larger fragments than those shed by other comets, which is why this meteor stream occasionally delivers a few unusually bright meteors known as "fireballs." Encke's has the shortest known orbital period for a comet, taking only 3.3 years to make one complete trip around the sun.

Related: How comets cause meteor showers

Two Streams for the Price of One

The Taurids are actually divided into the Northern Taurids and the Southern Taurids. This is an example of what happens to a meteor stream when it grows old. Even at the beginning, the particles could not have been moving in exactly the same orbit as their parent comet; their slight divergence accumulates with time.

The sun is not the only body gravitationally controlling the particles' orbits; the planets are having their own subtle effects on the stream. As the positions of the planets are constantly changing, the particles pass nearer to them on some revolutions than on others — diverting parts of the stream, fanning it out and splitting it. So, what was originally one stream diffuses into a cloud of minor streams and isolated particles in individual orbits, crossing Earth's orbit at yet more widely scattered times of the year and coming from more scattered directions until they are entirely stirred into the general haze of dust in the solar system.

The two radiants, or points where the meteors appear to originate in the sky, lie just south of the Pleiades star cluster. So, during the next couple of weeks, if you see a bright, slightly tinted orange meteor sliding rather lazily away from that famous little smudge of stars, you can be sure it was likely a Taurid.

A swarm of comet chunks

Dr. Victor Clube, an English astrophysicist and expert on comets and cosmology, suggested in a 1991 paper that the Taurid meteor stream contains perhaps a half a dozen full-size asteroids whose orbits place them squarely in the stream. Clube and his colleagues argue that the Taurids' range of orbits indicates they were all shed by a huge comet, originally 100 miles (160 kilometers) across or more, that entered the inner solar system some 20,000 years ago. By 10,000 years ago it was desiccated and brittle; Encke's Comet might actually be the biggest leftover chunk.

Some astronomers, believe that another branch of the Taurid swarm — one that Earth interacts

with at another part of our orbit, in June, might have given rise to the famous Tunguska

meteor event over northeast Siberia in 1908.

Encke's has the shortest known orbital period for a comet, taking only 3.3 years to make one complete trip around the sun. Meteor expert David Asher has advanced a theory of a "resonant meteoroid swarm" within the Taurid Complex. Briefly, it predicts that in specific years, the Earth is hit by a greater number (than in average years) of meteoroids capable of producing Taurid fireballs.

According to Asher, the next "swarm year" is in 2022. But in a stroke of bad timing, the moon will turn full on November 8th, right in the middle of the "prime viewing period" for that year.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.