SpaceX launches Turksat 5A communications satellite for Turkey, lands rocket

The launch kicked off what should be a very busy 2021 for Elon Musk's company.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. — SpaceX kicked off what is expected to be another launch-packed year by delivering a Turkish communications satellite to orbit tonight (Jan. 7).

A 230-ft-tall (70 m) Falcon 9 rocket blasted off from Space Launch Complex 40 here at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station at 9:15 p.m. EST (0215 GMT on Jan. 8), about 45 minutes into a planned four-hour window, carrying the Turksat 5A satellite into space. The brief delay was due to a downrange tracking issue, SpaceX said during its live launch broadcast.

Going into the launch tonight, forecasters at the U.S. Space Force's 45th Space Wing predicted a 70% chance of favorable conditions for launch, with the main concerns being cumulus and thick clouds, along with upper-level wind shear. These conditions aren't always ideal for onlookers but can allow interesting acoustics as the roar of the Falcon sounds extra loud.

Related: SpaceX's very big year: A 2020 filled with astronaut launches, Starship tests and more

Falcon's flight

The two-stage Falcon 9 lit up the night sky as it leapt off the launch pad tonight. The glow of the rocket's nine first-stage engines turned night into day as the rocket climbed into the clouds hanging over the Space Coast. The rumble of the engines could be heard long after the rocket disappeared from sight.

Tonight's mission marked the first launch of the year here at the Cape, and 8.5 minutes after liftoff, the rocket's first stage landed on one of SpaceX's two massive drone ships, "Just Read the Instructions," which was stationed out in the Atlantic Ocean.

Today's flight was the fourth launch for this particular Falcon 9 first stage. The booster, designated B1060, previously lofted an upgraded GPS III satellite for the U.S. Space Force in June 2020, followed by launches of SpaceX's Starlink internet satellites in September and October.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Falcon 9 went vertical on the pad this morning. SpaceX did not conduct a static fire test of this particular rocket before flight. Typically, the company holds the rocket down on the pad and briefly fires its nine first-stage engines to make sure their systems are working as expected prior to liftoff. It's rare that SpaceX skips this routine test, but it's not unheard of. In fact, SpaceX skipped the static fire test on its previous mission as well, which launched a spy satellite for the U.S. National Reconnaissance Office in December.

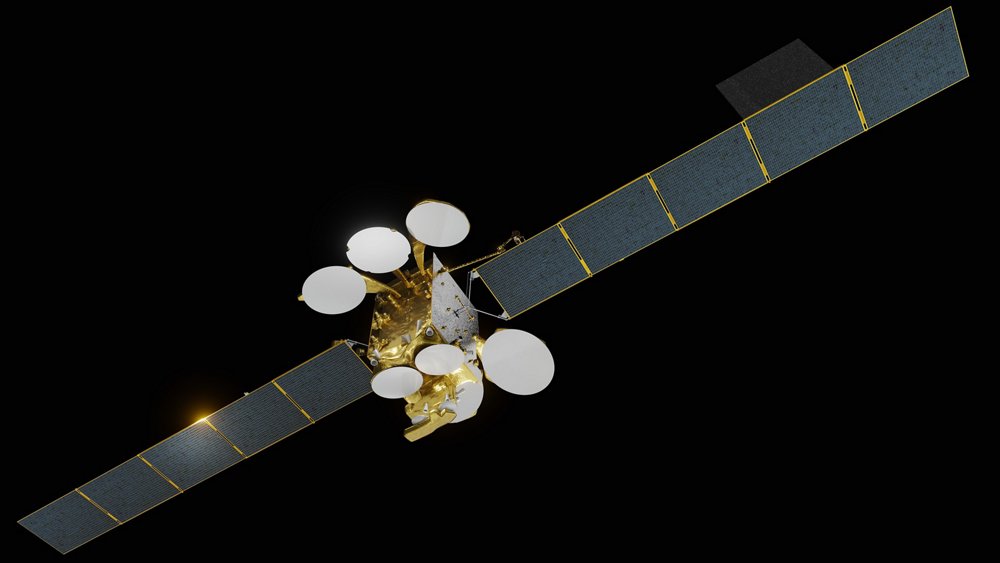

Powered by more than 1.7 million pounds of thrust from its nine first-stage Merlin 1D engines, the Falcon 9 deposited the 7,700-lb. (3,500 kilograms) Turksat 5A satellite into orbit about 33 minutes after liftoff. The spacecraft is designed to operate for approximately 15 years, providing broadband coverage to Turkey, the Middle East, Europe and portions of Africa.

SpaceX will also launch the spacecraft's counterpart, Turksat 5B, later this year. The Turksats are part of an effort to expand Turkey's presence in space, which hasn't been without controversy. In October, activists began pressuring SpaceX to stop the Turksat 5A launch. They protested outside SpaceX's headquarters in Hawthorne, California, citing Turkey's role in a conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan as the reason the mission shouldn't fly. Their attempt was unsuccessful.

About 8.5 minutes after Falcon 9 leapt off the pad, the rocket's first stage landed on the drone ship, marking the third successful launch and landing for this particular booster. The landing also marked the 71st successful touchdown for a returning SpaceX booster overall and the 21st in a row. (In 2019, SpaceX lost two first-stage boosters in back-to-back missions as the vehicles failed to hit their mark.)

Related: Hundreds gather at SpaceX HQ to protest Turkish satellite launch

Expanding Turkey's space presence

Built by Airbus, the Turksat 5A spacecraft separated from the Falcon's upper stage approximately 30 minutes after liftoff. From its orbital perch, more than 22,000 miles (36,00 kilometers) above Earth, the satellite will beam down broadband coverage, thanks to its 42 Ku-band transponders.

It will take the satellite nearly four months to reach its final altitude. Turksat 5A will make the trek using its onboard plasma thrusters, which rely on electrical energy from the spacecraft's solar panels rather than traditional fuel. These thrusters are more energy efficient but produce less thrust, so it takes a bit longer to reach its orbital parking spot.

“We are very pleased to welcome Turksat as a new Eurostar customer for the most powerful satellites of their fleet. We were the first to demonstrate full electric propulsion technology for satellites of this size and capacity, and this will enable the Turksat spacecraft to be launched in the most cost-efficient manner,” Nicolas Chamussy, head of space systems at Airbus, said in a company statement.

Turksat 5B, which is slated to launch later this year, is a bit heavier than its predecessor. Weighing in at more than 9,000 lbs. (4,500 kg), the satellite will operate in both the Ku and Ka bands, providing more than 50 gigabits per second of capacity, according to Airbus. That satellite is expected to enter service later this year, if all goes as planned.

Satellite quiz: How well do you know what's orbiting Earth?

Stick it to the drone ship

The Turksat 5A mission is SpaceX's 50th reflight of a Falcon 9 since the company recovered a booster for the first time in 2015.

To stick the landing, the booster separated from its upper stage and conducted a series of orbital ballet moves, to reorient itself for landing. Then it performed a series of three engine burns to slow itself enough to gently touch down on its designated landing spot, the deck of "Just Read the Instructions."

To facilitate reuse, SpaceX employs two massive drone ships, the second of which is named "Of Course I Still Love You." The floating platforms are stationed in the Atlantic prior to launches from the Space Coast and return to Port Canaveral with the booster in tow following a successful catch. These two vessels have enabled SpaceX to launch and subsequently land more rockets.

"Of Course I Still Love You" is now receiving some TLC after a busy year last year. In total OCISLY has caught 40 returning boosters, 13 of which landed in 2020. The ship will soon return to service, ready to catch many more boosters with SpaceX's busy schedule for this year.

"Just Read the Instructions" received its own upgrades and renovations at the beginning of 2020.

Reusability efforts

The current iteration of the Falcon 9 debuted in 2018. Known as the Block 5, it features 1.7 million pounds of first-stage thrust as well as some other upgrades that make it capable of rapid reuse. According to SpaceX, each of these first-stage boosters can fly as many as 10 times with minor refurbishments in between, and potentially as many as 100 times before retirement.

To date, SpaceX has launched and landed the same booster a maximum of seven times. So far we have yet to see one fly 10 times, but that could happen this year.

Company founder and CEO Elon Musk has said that he wants his rockets to help facilitate access to space, and the Block 5 Falcon 9 was created to do that. Thanks to the launcher's capabilities, it has enabled smaller countries and organizations to reach space through dedicated missions and "rideshares."

With this flight, Turkey has become the latest country to take advantage of that opportunity. A little over two years ago, Bangladesh sent its first-ever communications satellite into space atop a SpaceX rocket; last July, South Korea launched its first dedicated military satellite from Florida's Space Coast; and in 2018, Israel launched a spacecraft to the moon as part of a rideshare mission. These are just a few examples of the growing number of countries and entities that are reaching for the stars thanks to reduced launch costs.

Fairing recovery

Ahead of today's launch, SpaceX deployed its dynamic duo — GO Ms. Tree and GO Ms. Chief — in an effort to fetch the two falling pieces of the Falcon 9's payload fairing, or nose cone.

Ms. Tree had been working solo for the final few missions of 2020, getting an assist from a boat named GO Navigator.

Ms. Tree and Ms. Chief serve as giant, mobile catcher's mitts, snagging payload fairings in their attached nets as they fall back down to Earth. (The boats are also capable of retrieving fairing halves rom the water after they splash down.)

Each fairing piece is equipped with parachutes and special software to guide itself to a predetermined recovery zone where the boats are waiting with their outstretched nets.

Once returned to port, the fairings are refurbished and used again. Typically, SpaceX flies used fairing pieces on its own Starlink missions, but the company has been branching out and using more reused hardware on all its missions. In December, the company flew a veteran fairing on its Sirius XM-7 mission, the first external mission to feature a refurbished shroud.

Today's mission marks the beginning of a busy launch year for the Cape. More than 40 missions are on the schedule, with SpaceX hoping to launch 40 rockets this year between its California and Florida launch sites.

Those launches include two astronaut missions to the International Space Station, more Starlink flights, and one liftoff of SpaceX's powerful Falcon Heavy.

Up next for SpaceX is the Transporter-1 mission, which is slated to transport 72 small satellites along with four additional payloads into space as part of SpaceX's latest rideshare endeavor. Transporter-1's liftoff is scheduled for no earlier than Jan. 14.

Follow Amy Thompson on Twitter @astrogingersnap. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Amy Thompson is a Florida-based space and science journalist, who joined Space.com as a contributing writer in 2015. She's passionate about all things space and is a huge science and science-fiction geek. Star Wars is her favorite fandom, with that sassy little droid, R2D2 being her favorite. She studied science at the University of Florida, earning a degree in microbiology. Her work has also been published in Newsweek, VICE, Smithsonian, and many more. Now she chases rockets, writing about launches, commercial space, space station science, and everything in between.