Space Radiation Will Damage Mars Astronauts' Brains

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

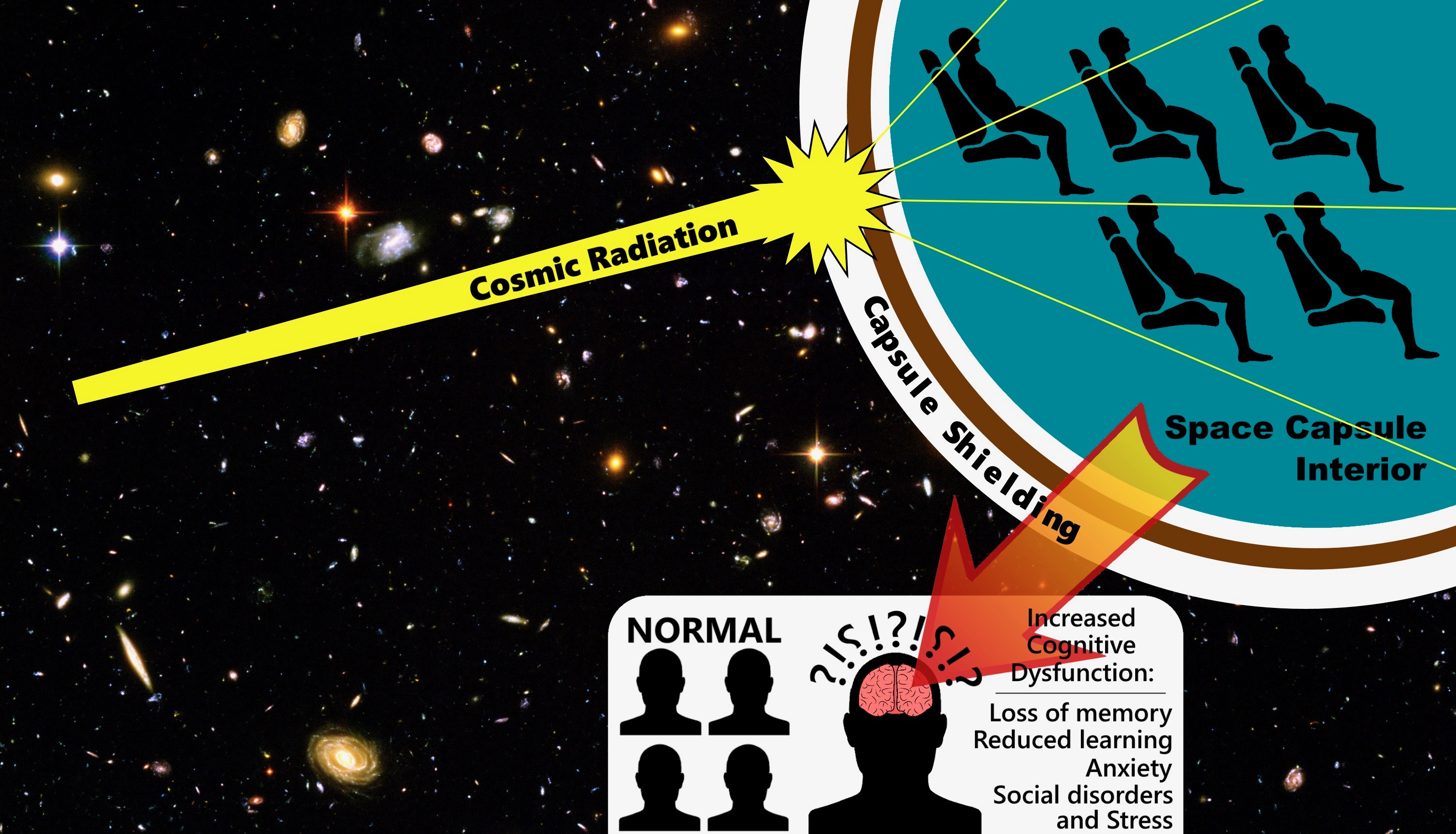

Space radiation will take a toll on astronauts' brains during the long journey to Mars, a new study suggests.

Mice exposed for six months to the radiation levels prevalent in interplanetary space exhibited serious memory and learning impairments, and they became more anxious and fearful as well, the study reports.

The trip to Mars takes six to nine months one way with current propulsion technology. So, these results should ring a cautionary bell for NASA and other organizations that aim to send people to the Red Planet, study team members said.

Related: How Space Radiation Threatens Human Exploration (Infographic)

"This is not a deal-breaker for space travel, but when you send astronauts up there, you have to be prepared for what some of the consequences are for being exposed to these radiation fields," said study co-author Charles Limoli, a professor of radiation oncology at the University of California, Irvine (UCI) School of Medicine.

"These chronic low-dose-rate, low-dose-exposure scenarios are going to increase the risk of developing, perhaps, mission-critical performance deficits," Limoli told Space.com. "What exactly those are, we'll never know until we get out there."

Researchers investigating the effects of deep-space radiation have historically given lab animals acute doses — high levels over a relatively short period of time. But Limoli and his colleagues — led by Munjal Acharya and Janet Baulch of UCI's Department of Radiation Oncology and Peter Klein of Stanford University's Department of Neurosurgery — took a different tack.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Using a neutron-irradiation facility, they exposed 40 mice to 1 milligray of radiation per day (1 mGy/day) for six months, about the same dose and duration that astronauts would experience on a trip to or from Mars. (Astronauts in low Earth orbit are exposed to lower doses, because they're protected by our planet's magnetosphere.)

"This is the first study that's looked at space-relevant dose rates," Limoli said. "And this is the first study to analyze the consequences of the low dose rate over the course of time on functional endpoints in the brain."

The researchers analyzed the behavior of these mice over the course of the study, measuring the animals' ability to learn and remember information, their willingness to interact with new mice introduced into their enclosure, and other variables. And at the end of the six months, the scientists euthanized the mice and studied their brains, looking for physiological changes.

All of these measurements and observations were compared with those gathered from a control group of 40 mice, which did not receive the 1 mGy/day dose.

Related: How Living on Mars Could Challenge Colonists (Infographic)

The results were striking. Radiation-exposed mice exhibited more stress behaviors and a decreased ability to learn and remember. The physiological work bolstered these behavioral findings, identifying impaired cellular signaling in two key areas of the brain: the hippocampus, which is associated with learning and memory, and the prefrontal cortex, the site of many complex cognitive functions.

The researchers said they aren't sure what caused these physiological effects in the brain; the team didn't trace out the molecular pathways involved. But the low radiation doses employed suggest that the impacts are probably not the result of cell death or DNA damage, Limoli said.

NASA is keenly aware of, and interested in, these results; the space agency helped fund the new study, which was published Monday (Aug. 5) in eNeuro, the Society for Neuroscience's open-access journal.

The anxiety and depression effects shouldn't be a big deal for NASA going forward, Limoli said; the agency can screen potential Mars astronauts with such impacts in mind. But the learning and memory impairments present a more serious concern, he added.

The effects of chronic radiation exposure "would probably manifest in a scenario where the astronauts have to deal with some unanticipated event where there's some on-the-spot decision-making or problem-solving involved," Limoli said.

"Is it going to cause them to forget their long-term memories or forget how to fly the spacecraft? Of course not," he added. "But these subtle manifestations of impairment may prove problematic under certain emergencies, for example."

Limoli stressed that low-dose, background radiation exposure is not a showstopper for crewed Mars missions. Rather, it's a significant risk-increasing factor that needs to be taken into consideration when planning such trips, which NASA aims to achieve in the 2030s.

But the story may well be different for interstellar flight, which will require much longer travel times (barring big breakthroughs in propulsion technology, of course) — and therefore much higher cumulative radiation exposures for anyone aboard.

"I anticipate that the radiation problem in space may be one of the biggest problems humans ever have to solve to get out of the solar system," Limoli said. "The radiation in space may keep us in our solar system for a long time."

- Anti-Radiation Vest to Get Deep-Space Test Next Year

- How We Could Make Mars Habitable, One Patch of Ground at a Time

- These Stunning Designs Show What Our Future on Mars Might Look Like

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.