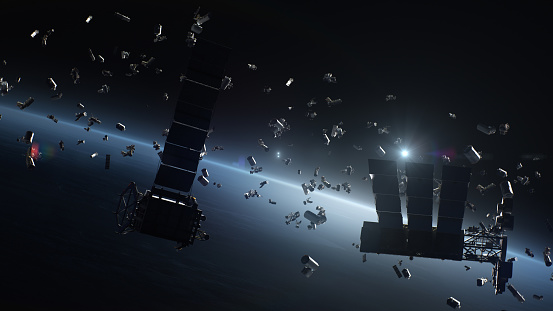

Solving space junk problem may require lasers and space tugs, NASA says

"Some remediation approaches may achieve net benefits in under a decade."

A new NASA report finds the space debris problem could be greatly reduced in as little as 10 years, with a little help from lasers or space tugs.

Dealing with the many thousands of pieces of space debris generated by more than 60 years of rocket launches could be done at relevantly low cost and swift speed, if operators focus on removing the smallest pieces or nudging bigger satellites out of the way of collision, the March 10 report states.

Removing space debris would have positive implications for missions to the International Space Station, which has had to maneuver out of the way of space debris twice in the past week alone. Satellites in low Earth orbit like SpaceX's Starlink are also responsible for numerous close encounters in space.

While space junk removal plans are in their infancy, the report emphasizes there is a pathway to success as long as the space community works together and is clear about where to prioritize solving the problem. There is hope, however: The report says "some remediation approaches may achieve net benefits in under a decade" once a viable method is put in place.

Related: How often does the International Space Station have to dodge space debris?

While it is difficult to quantify the space debris risk (as not all pieces are trackable), humanity has sent more than 15,000 satellites aloft since the first 1957 launch of the Soviet Union's Sputnik, and only about 7,200 of that number are operational, according to the European Space Agency's December 2022 figures. A recent paper in the journal Science calling for an international treaty to address space debris says there might be 100 trillion pieces of junk floating out there.

Some of these satellites have shattered due to accidental collision or deliberate destruction. A notable recent incident was a Russian anti-satellite debris test in 2021 that created so much debris it interfered with both ISS and Starlink operations.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

NASA's 147-page report assesses numerous options to remove debris in orbit, mostly targeting the smallest pieces (4 inches/10 cm and smaller) or entire satellites. Lasers appear to be one of the leading options, although the report is not calling for any particular action; that method is discussed twice (for ground-based and space-based lasers) in three separate options for removing small debris, and once among five options for taking out large debris.

Lasers appear to particularly be useful when trying to remove large numbers of small debris, as both space- and ground--based lasers alike are forecasted to provide a net benefit in terms of cost. But other options such as space tugs or manually moving pieces out of the way are also considered.

Laser-nudging the top 50 objects of concern also would useful, the report says, although higher-cost options such as rocket nudges could work more rapidly. The authors emphasized that their discussion, however, should be taken as a beginning to addressing the problem in the near future.

"Rather than relying on proxies for risk such as the number or mass of debris, this report aims to encourage the space community to take a holistic approach to framing the risks of space debris in terms of dollars and how debris may affect satellite operators in the coming decades," the authors said.

Some early-stage projects show promise, such as the ELSA-d spacecraft of Japan-based startup Astroscale that captured a simulated piece of space junk in 2021, and a European Space Agency effort with ClearSpace-1 to test debris removal efforts as soon as 2025. NASA also announced this week it will seek a $1 billion space tug to safely remove the ISS when the orbiting complex concludes operations in 2030 or so.

Elizabeth Howell is the co-author of "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022; with Canadian astronaut Dave Williams), a book about space medicine. Follow her on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.